INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), a relapsing disorder characterized by chronic idiopathic gastrointestinal (GI) tract inflammation, is categorized into ulcerative colitis (UC) and CrohnŌĆÖs disease [

1]. Although environmental and genetic factors contribute to IBD progression, the exact etiology of the disease remains unclear. Currently, it is hypothesized that GI microbes may trigger a deregulated immune response in genetically predisposed individuals, resulting in chronic inflammation [

2,

3]. As mediators of a chronic immune response, these microbes may play a key role in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases, such as asthma, vasculitic diseases, and IBD [

4]. The

Helicobacter genus is implicated as a potential pathogenetic contributor to IBD5 and reportedly triggers IBD-like colitis in an immunocompromised murine model [

5].

However, many epidemiological studies have suggested a negative association between

H. pylori infection and UC [

6]. Korean studies have reported an increase in the prevalence of UC with a simultaneous decrease in that of

H. pylori [

7]. Based on the inverse prevalence between

H. pylori infection and UC, recent studies suggest a protective role of

H. pylori infection against UC [

8-

10]. However, epidemiological studies can only suggest associations and do not establish cause-and-effect relationships. Assuming a potential protective effect of

H. pylori in UC, it is reasonable to conclude that the severity of UC may be lesser in patients with than in those without

H. pylori infection. However, few studies have discussed the clinical association between

H. pylori infection and severity of UC.

In this study, we investigated the association, if any, between severity of UC and H. pylori infection.

DISCUSSION

In this study, the

H. pylori infection rate in patients with newly diagnosed UC was 23.4%; disease prevalence was significantly lower than that observed in the general Korean population (41.5%ŌĆō66.9%) [

14,

15] throughout the duration similar to our study period. This result was consistent with findings reported by previous studies, which indicates a negative association between

H. pylori infection and UC [

2,

6,

16]. Notably, the

H. pylori infection status did not affect the severity of UC, including the severity of endoscopic findings, clinical symptoms, treatment regimen, and Mayo scores.

Numerous studies have investigated the effect of

H. pylori infection on UC; however, these studies have reported conflicting results. Some studies suggest a protective effect of

H. pylori infection against autoimmune diseases such as asthma, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and IBD [

2,

9,

10]. Laboratory evidence, which highlights the role of

H. pylori infection in immune system dysregulation, supports this impression. This finding indicates that

H. pylori, through its interaction with dendritic cells, can upregulate regulatory T cells, with decreased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which consequently may downregulate the systemic immune response and suppress autoimmunity [

2]. Another potential mechanism underlying the protective role of

H. pylori infection is the differential expression of an acute and/or chronic local mucosal inflammatory response [

17,

18].

H. pylori may induce the production of antibacterial peptides that counteract potentially harmful bacteria implicated in the pathogenesis of IBD [

17,

18]. Several clinical studies have investigated the association between

H. pylori infection and UC progression, which reflects disease activity [

19-

21]. The results of these studies show that

H. pylori positivity rates were lower in patients with UC who present with pancolitis than in those with more limited disease. Reportedly,

H. pylori colonization has an independent protective effect against UC disease activity.

Some other studies have reported that

H. pylori infection does not protect against UC and is not associated with UC activity [

1,

22-

24]. In these studies, the incidence of

H. pylori in patients with IBD was the same as that observed in the normal population, and

H. pylori infection was not significantly associated with disease extent, stool frequency, rate of admission necessitated by disease aggravation, and treatment regimen (oral or intravenous steroid therapy), which indicates a severe disease status [

24,

25]. However, it is important to consider the limitations of the small-scale study (42 patients) [

23] and that detailed categorization for evaluation of UC activity was not reported.

In our study, we investigated the association between UC activity and

H. pylori infection in a relatively large number of patients with newly diagnosed UC. Disease activity was classified in detail using various indices, including endoscopic findings, patient symptoms, treatment regimen, and Mayo scores. Endoscopically, UC is characterized by inflammatory changes observed immediately above the anorectal junction that extend proximally in a confluent and continuous manner [

26]. Therefore, disease localization is easy in patients with UC. Estimation of endoscopic extent and findings is widely used to evaluate IBD severity because endoscopic severity correlates with symptom severity and is significantly correlated with histopathological findings. Stool frequency and rectal bleeding were also evaluated because these symptoms can be easily assessed and are more objective parameters compared with the patientŌĆÖs or physicianŌĆÖs global assessment. Disease activity was estimated on the basis of the induction treatment regimen. We concluded that administration of steroid, azathioprine, or infliximab as induction therapy was common in patients with severe UC and that sulfasalazine and 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy was primarily used in those with less severe disease. To avoid the possibility of spontaneous eradication of

H. pylori following antibiotic therapy (particularly metronidazole), sulfasalazine, and other aminosalicylic compounds commonly used for management of UC, we only enrolled patients with newly diagnosed treatment-naïve UC and without

H. pylori eradication treatment history.

Interestingly, in this study, we observed an inverse association between H. pylori infection and UC, which concurs with the findings of many epidemiological studies that have reported a low incidence of H. pylori infection in patients with IBD. In this study, we did not observe a protective effect of H. pylori against UC, which suggests that the inverse association may be ascribed to a coincident phenomenon and does not indicate a cause-and-effect relationship. Therefore, the lower incidence of H. pylori infection in patients with UC may be attributable to the role of other confounders such as inherent genetic or environmental factors that favor H. pylori infection in some patients and the development of IBD in some others.

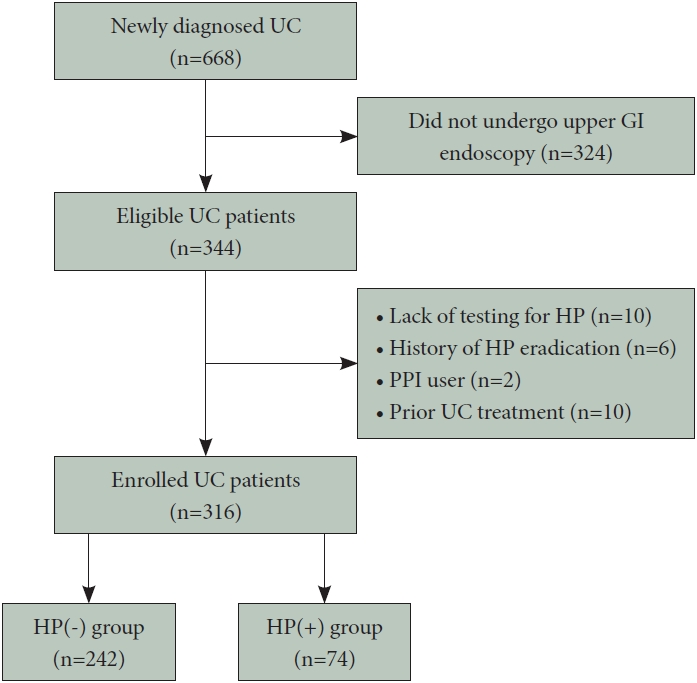

Following are the limitations of this study. First, we could not address the role of potential confounders that may have affected our results. For example, low socioeconomic status may be a strong common confounder that could account for both the higher prevalence of H. pylori infection and lower prevalence of IBD observed in the study. Second, we did not investigate the effects of H. pylori eradication therapy on UC activity. Follow-up of the disease course without treatment for UC after H. pylori eradication is difficult in patients with UC, and further prospective studies are warranted to conclusively determine the exact effect of H. pylori eradication on UC disease activity. Third, we evaluated the gastric H. pylori infection status but not the H. pylori status throughout the colonic mucosa; therefore, we could not compare disease activity based on colonic H. pylori infection. Future clinical studies should investigate the effects of H. pylori on disease activity in the intestinal mucosa of patients with UC. Fourth, a selection bias cannot be excluded; H. pylori testing was not performed in all patients with newly diagnosed UC. We evaluated H. pylori infection at the physicianŌĆÖs discretion in patients who presented with dyspepsia, a history of gastric cancer, and endoscopic findings, including peptic ulcers, gastric polyps, and atrophic gastritis. Further research, including prospective cohort studies, is warranted.

In conclusion, the H. pylori infection rate in our study (23.4%) was lower in patients with UC than in the general population. Moreover, H. pylori infection did not affect endoscopic severity, symptom severity, induction therapy, or the Mayo score classification, which suggests that H. pylori infection is not associated with UC disease activity. Further prospective studies are required to conclusively establish whether H. pylori infection affects UC onset and produces chronic effects on the natural course of the disease.