경피내시경위루술: 삽입과 관리

Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy: Insertion and Management

Article information

Trans Abstract

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is the modality of choice for long-term enteral feeding in patients in whom oral intake is challenging. Compared with parenteral nutrition, gastrostomy feeding is the preferred choice for sustained nutritional support. Delivery of nutrients directly to the gastrointestinal tract and enhanced cellular immunity associated with this approach are clinically beneficial to patients. Endoscopic gastrostomy is favored for its high clinical success rates and economic advantages and is associated with minor discrepancies with regard to morbidity, mortality, and tube function compared with surgical gastrostomy. PEG procedures can be broadly classified into the pull- and push-types. Although PEG is a comparatively safe procedure, high risk of bleeding is a well-known complication of PEG placement, which necessitates prophylactic antibiotic therapy and careful periprocedural management in patients who receive antiplatelet and anticoagulant agents. Tube dislodgement, peristomal leakage, or infection following PEG placement may require tube replacement or removal. In this review, we investigated the concerns associated with early vs. delayed feeding in concordance with current guidelines. We also describe the indications for PEG tube insertion, post-procedural care strategies, and management of complications.

서 론

경피내시경위루술(percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, PEG)은 정맥영양으로 영양공급과 유지가 어려운 환자를 대상으로 경장영양을 공급할 목적으로 구강과 식도를 우회하여 위장 내로 직접적인 영양공급 경로를 만드는 내시경 술기이다. 경장영양은 정맥영양과 비교해서 소화관의 생리적 기능유지, 영양소 흡수, 감염 합병증 등의 측면에서 우수하므로 우선적으로 고려되어야 한다[1,2]. PEG는 경장영양법의 한 형태로 4주 이상 경비위관 거치가 필요한 삼킴곤란이 있는 환자에서 일차적으로 고려하게 되며, 위 구조가 수술 등으로 변형되었거나 위 배출 장애가 있는 경우, 역류로 인한 흡인이 문제가 될 경우에는 PEG보다는 공장루 등의 다른 접근법이 필요하다.

PEG는 1981년 최초로 소개된 이후로 국내에서 시술 건수 및 시술 받는 환자 수가 꾸준히 증가하고 있다[3]. PEG는 쉬운 접근성과 낮은 실패율로 경험이 적은 시술자도 쉽게 시행할 수 있다[4]. 그러나, PEG는 복측 피부 절개와 함께 위장 천공을 유도해야 하는 침습적 시술로 감염과 출혈을 포함하여 다양한 합병증이 동반될 수 있다[5,6]. 이러한 부작용에도 불구하고, PEG는 경구식이의 진행에 어려움이 있거나, 고열량 영양 공급이 장기적으로 필요한 임상 상황에서는 반드시 필요한 시술이다. 따라서, PEG는 시술에 대한 적절한 적응증과 금기증에 따라 시행되어야 한다[7]. PEG와 관련하여 미국과 유럽 등 국외 가이드라인들이 있으며 최근 국내에서도 이에 대한 임상진료지침이 발간되었다[8-11]. 본 종설은 이러한 가이드라인들을 중심으로 PEG가 올바르게 시행되어야 하는 임상적 상황에 관하여 알아보았고, 삽입과 시술 전후 일반적 관리 및 합병증 대처에 관하여 기술하였다.

본 론

적응증과 금기증

적응증

PEG는 경구 섭취를 통한 영양공급이 어려운 환자를 대상으로 진행된다(Table 1) [8,11-13]. 현재까지 PEG의 적응증 자체에 대해 조사한 연구는 없다. 그러나, 기존 가이드라인 및 연구들로부터 종합해보면, 삼킴곤란, 삼킴장애 증상을 가진 급성 뇌경색, 뇌출혈로 인한 신경학적 결손 환자, 만성 진행성 신경학적 결손 환자, 혼수상태 환자, 인후두부 및 식도의 악성 신생물 환자, 암 악액질 환자, 기타 심한 외상과 기도삽관 등으로 장기적인 영양공급이 필요한 중환자실 환자 등에서 적합하다[8,12]. 최근 발표된 국내가이드라인은 4주 이상의 경비위관의 거치가 필요한 삼킴곤란증을 가진 환자로 폭넓게 대상을 규정하고 있다[11].

금기증

PEG의 금기증은 일반적으로 경장영양공급의 금기증과 동일하다. 금기증은 해부학적으로 내시경을 위에 삽입하기 어렵거나 위 절제 등으로 위루관을 삽입할 위치가 나오지 않아 접근 경로에 문제가 있는 경우가 해당하며 이 때 방사선투시 유도하 경피위루술(percutaneous radiologic inserted gastrostomy), 수술적 위루술(surgical gastrostomy)이나 수술적 공장루술(surgical jejunostomy)을 시도할 수 있다. 즉, 위전절제술, 위부분절제술, 대장치환술(colonic interposition) 등으로 인한 정상적인 위장관 위치의 변형, 위장관 폐쇄(기계성, 마비성), 출혈, 염증 및 천공, 혈액응고장애(INR >1.5, partial thromboplastin time >50초, 혈소판 <50000/mm3), 흡수장애, 심한 단장 증후군(short-bowel syndrome), 장 누공(intestinal fistula)으로 인한 소실이 심한 경우, 중증 비만, 다량의 복수, 식도 및 위 정맥류, 안면부 수술 등이 PEG의 금기증에 해당한다. 치매의 경우 환자들에서 위루술이 진행된 사례가 많지만 실행하는 데 있어서는 논란의 여지가 있다. 유럽소화기내시경학회 가이드라인에서는 진행된 치매 환자에서 위루술을 삼가할 것을 권고하고 있으나, 국내 임상진료지침에서는 위루술의 적응증에 해당한다[8]. 또한 삶의 여명이 한 달 이내인 환자에게는 경장영양을 권고하지 않기 때문에 PEG의 금기증에 해당한다[8,13].

삽입 전 관리

투 약

항생제

항생제는 PEG에서 시술 후 감염의 위험을 줄이기 위해 반드시 사용되어야 한다. Beta-lactam 계열의 단회투여(single dose) 항생제를 시술 30분 전에 정맥으로 사용하는 것만으로도 시술 이후 1주일간의 감염 위험도를 감소시킬 수 있는것으로 보고되었다[14,15]. 국내 진료지침은 위루관의 종류에 따라 항생제 사용을 구분하였는데, 당김형을 삽입하는 환자에서는 한 번 이상의 항생제 사용을 권고하였다[11]. 이는 당김형에 대한 연구 12건과 밀기형에 대한 연구 2건의 메타분석을 통해 도출되었으며, 밀기형에서의 항생제 사용은 추후 추가적인 연구들을 통한 근거가 필요할 것으로 보인다. 국내 임상 진료지침에서 특정 항생제의 선택에 대한 권고는 없으나, 유럽 가이드라인에서는 beta-lactam 계열 항생제를 권고하였으며, 이전 메타분석에 따르면 penicillin이 cephalosporin보다 절대 위험도 감소가 13% 대 10%로 더 크다는 보고가 있었다[9,11,16]. 이밖에 항생제 부작용으로는 Clostridioides difficile-associated diarrhea (3/33, 3.03%)가 가장 흔하며[14], 이외에도 구역 증상이 있었으나 그 빈도는 설사보다 훨씬 적게 보고된다[17].

항혈전제

미국소화기내시경학회 가이드라인에 따르면 PEG는 출혈에 대한 고위험 시술로 분류되며, 환자군은 혈전 부작용의 위험도에 따라 저등급과 고등급으로 분류되고 위험도에 따라 항혈소판제나 항응고제의 중단 및 재개 시점은 신중하게 고려하여 결정해야 한다[18]. 일부 환자에서는 순환기내과 의사와 상의하여 항혈전제의 조절이 필요하다. 특히, 항응고제 중단 이후 혈전색전증 발생 위험이 높은 군(CHA2DS2-VASc>5 이상의 비판막성 심방세동, 심방세동이 동반된 승모판 협착증, 승모판막치환술, 정맥혈전증 발생 3개월 이내)에서는 와파린의 중단과 함께 헤파린 가교 요법이 고려되어야 한다. PEG가 예정된 환자에서 와파린의 사용으로 인하여 출혈 위험이 있을 것으로 예상되는 경우 혈액응고검사를 시행해야 한다. 최근 대한소화기내시경학회에서 발표한 내시경 시술 전 후 항혈전제 사용 임상진료지침에 따르면 각 항혈전제의 종류에 따른 시술 전후 약제 중단과 재시작은 Table 2와 같다[19].

삽입 방법

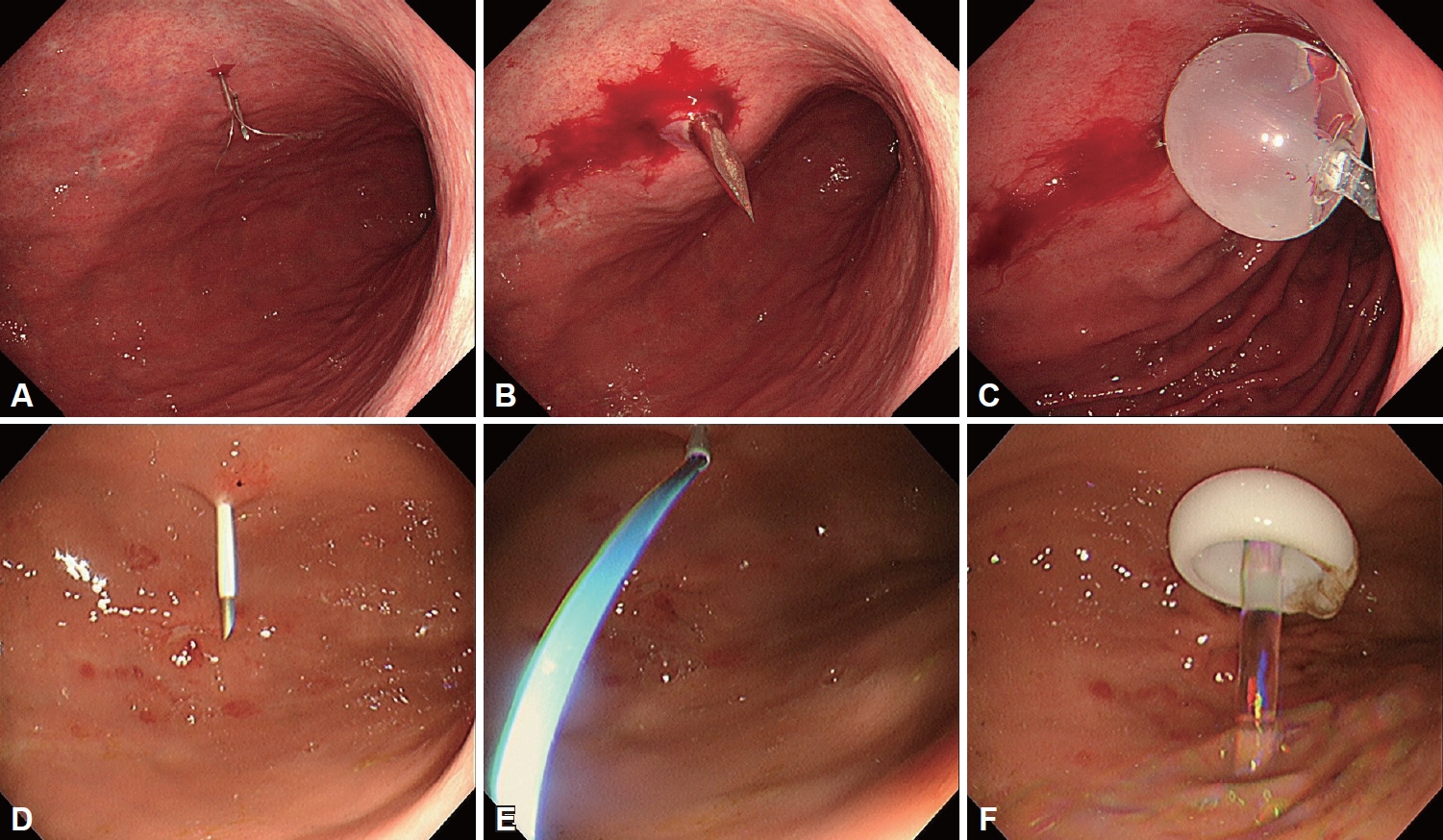

PEG의 삽입 방법은 크게 당김형과 밀기형으로 나뉜다(Fig. 1). 대표적으로 국내 사용가능한 제품에는 당김형의 PEG-24-PULL (Cook Medical Inc., Bloomington, IN, USA), MIC (Avanos Medical Sales LLC, Alpharetta, GA, USA)와 밀기형의 CLINY (Create Medic Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan)가 있다. 일반적으로 많이 사용하는 당김형은 위내시경을 먼저 삽입하고, 좌측 갈비뼈 아래와 검상돌기 아래 복부 중앙 부위의 사이에 천자할 부위를 내시경으로 확인한다. 천자한 뒤 내부의 천자침을 제거한 뒤 남은 카테터를 통해 유도선(guidewire)을 밀어넣는다. 위내시경으로 천자침이 뚫는 위치를 확인하고, 카테터를 통해 나온 유도선을 올가미로 잡아서 입 밖으로 빼낸다. 체외로 나온 유도선을 위루관과 연결하고, 카테터에 넣었던 유도선을 복부 밖으로 잡아당긴다. 이때, 위루관이 위에서부터 복벽쪽을 통과하여 잘 나올 수 있도록 나이프로 복부에 적당한 절개선을 만든다. 위내시경으로 위루관의 내부 완충기가 위점막에 고정되는 것을 확인하고 복벽의 외부 완충기를 설치함으로써 시술은 완성된다. 밀기형은 내시경을 이용하여 위를 부풀리는 과정까지는 당김형과 동일하나, 2개의 고정자를 이용하여 위벽을 복벽에 고정시킨 뒤, 작은 절개창을 고정자 사이에 만들고 절개창을 통해서 풍선형의 위루관을 직접 넣는다. 이후 풍선에 물을 넣고 고정시키고, 외부 완충기를 통해 고정시킨다. 밀기형은 경구로 위루관을 넣지 않는다는 점에서 당김형과 차이가 있다. 유럽소화기내시경학회 가이드라인은 일반적으로 당김형의 위루술을 권장하나, 식도종양 등의 임상적 상황에서는 밀기형을 권장하고 있다[9]. 국내 임상지침은 당김형과 밀기형의 선택은 시술자의 선호도에 따라 결정하는 것을 권장하나, 두경부암, 식도암의 환자에 있어서는 유럽과 마찬가지로 밀기형을 권고하였다[11].

Procedures for both push-type and pull-type percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (upper low, push-type; lower low, pull-type). A: After puncturing the marked site with both needles, the loop insertion rod is pushed forward to form a loop snare. B: Following the completion of percutaneous gastropexy, insert the PS needle through the skin incision. C: Inflate the balloon to secure it to the stomach. D: Insert the needle and cannula unit through the skin into the insufflated stomach. E: Looped insertion wire was inserted through the needle cannula. F: Internal bolster was fixed to the stomach.

삽입 후 관리

영양공급 시기

PEG로 공급관이 설치된 이후에는 적절한 영양공급이 시작되어야 한다. 영양공급 시기에 대해서 미국정맥경장영양학회 가이드라인에서는 신경학적 결손, 기계환기, 수술을 포함하는 중환자 중 고위험군에서는 위루술 후 영양공급을 24-48시간 이내에 할 것을 권고하였다[20]. 그러나, 2017년 미국정맥경장영양학회의 경장영양요법을 위한 안전한 진료(safe practice for enteral nutrition therapy)에서는 영양공급을 4시간 이내에 시행하는 것을 권고하였다[21]. 비교적 최근 발표된 2021년 유럽소화기내시경학회 가이드라인에서는 두 개의 메타분석 논문으로부터 4시간 이내의 조기 경장영양과 24시간이 지난 지연 경장영양을 비교하였다[9]. 그 결과 국소감염과 설사, 출혈, 구토, 누출, 72시간 이내 조기사망률 분석에서 양군 간에 유의한 차이가 없었다. 국내 임상진료지침에서 무작위 대조군 연구논문 5편의 메타분석을 실시한 결과[22-26], 시술 24시간 이내에 영양공급을 시행해도 된다고 권고하였다. 비록 권고강도 및 근거수준은 약하지만, 이전에 미국정맥경장영양학회 가이드라인에서 권고한 24-48시간은 대게 시술한 다음날이나 당일 오후에 영양공급을 시작하는 국내의 임상적 상황을 고려할 때 맞지 않는 부분이 있다. 그러나, 새로 제정된 국내 임상진료지침으로 근거수준이 마련되어 시술 의사에게 긍정적으로 평가될 수 있는 부분으로 보인다. 이러한 메타분석의 근거가 된 연구들은 1990년대 논문이 대부분으로, 이후에 PEG의 기구 및 기술이 다양하게 발전되었기 때문에 향후 이와 관련한 무작위 대조군 연구가 진행된다면 PEG 환자에게 조기 영양공급을 지지하는 임상적 근거가 될 수 있을 것으로 판단된다.

구강위생과 피부 소독

PEG를 받게 되는 환자는 전신 상태가 불량한 경우가 대부분이다. 이들의 구강위생 역시 불량한 경우가 많은데, 위루술을 받는 환자는 흡인성 폐렴 예방을 위해서라도 구강 위생 상태에 주의를 기울여야 한다. 일부에서는 교육의 부재로 보호자 및 주변인에 의하여 위루관 삽입 부위 주변에 규칙적으로 항생제 연고를 사용하고 과산화수소를 이용한 소독을 하게 되는데 이는 권장되지 않는다. 만약, 위루관 주위로 누출(peristomal leakage)이 발생한다면 지속적인 드레싱을 통해서 상처 부위를 깨끗이 소독하고 완전히 건조시키는 것이 필요하다[27]. 한편으로, 유럽소화기내시경학회 가이드라인은 위루관 설치 이후, 위루관 주변을 7일 정도 생리식염수로 소독하고 건조시키는 것을 권고하고 있다[9].

관막힘(clogging)

위루관은 형태 및 종류와 무관하게 막히기 쉽다. 대부분의 원인은 관세척(flushing)의 부족으로 발생하지만, 잔류량(residual volume)을 확인하는 것이 위험을 증가시킬 수 있다. 관막힘은 무엇보다도 위루관의 내경에 좌우되며 제조사에 따라서 다를 수 있지만, 외경이 동일한 관이라면 폴리우레탄 소재의 관이 실리콘보다 내경이 커서 덜 막힐 가능성이 높다. 이외에도 막힘의 원인으로 영양액(formula)의 영향이 있으며, 막힘을 최소로 하기 위해서는 고단백(high-protein)이나 고섬유(high-fiber) 제제를 사용하는 것이 좋다[28]. 투약과 관련해서는 영양공급 이후에 투약을 하고, 투약 이후에는 물로 깨끗하게 세척을 하며 역류하지 못하도록 잠가 놓는 것이 막힘을 줄일 수 있다. 이 밖에도, 예방적으로 췌장 효소(pancreatic enzyme)를 사용하는 것이 도움이 되는 것으로 알려져 있다[29]. 일단 위루관이 막힌 경우에는 콜라, 췌장 효소, 유도선 등을 이용해 해결해 볼 수 있다[30].

위루관 교체

위루관의 이탈(dislodgement)이나 파손, 부식, 지속되는 위루관 주위 감염, 누출, 피부궤양 등은 교체의 적응증이 된다. 내부 고정자가 있는 위루관은 2년 이상 사용이 가능하며, 풍선형 위루관은 3-6개월 간격으로 교체해줄 필요가 있다. 내부 고정자형 위루관으로 PEG를 시행하였을지라도, 교체는 풍선형으로 가능하다[11].

합병증 관리

위루관 주위 감염

위루관 주위 감염은 가장 흔한 합병증(30%)으로[31], 대부분은 경미하고 위루관 주변에 국소적으로 발생하지만, 2% 미만에서는 농양, 괴사성 근막염과 같은 심각한 합병증으로 진행된다[32]. 외부 고정자를 복벽으로부터 1 cm 정도 간격을 두는 것이 감염 발생을 줄여주며, 감염이 발생한 경우라면, 광범위 항생제를 경구 혹은 정맥으로 5-7일 정도 사용하는 것이 안전하다(Table 3).

위루관 이탈

위루관 이탈은 상대적으로 빈도가 흔한 부작용(13%-29%)으로, 주로 인지장애(cognitive disorder) 환자에서 위루관을 복벽 밖으로 잡아당김으로 인해 발생한다[33,34]. 4주를 기준으로 위루관 트랙이 안정적으로 형성되기 때문에 4주를 넘어서 발생한 위루관 이탈은 새로운 위루관으로 교체하면 되며, 일시적으로 도뇨관을 삽입하여 트랙을 유지하는 데 사용할 수 있다. 그러나, 4주 이내에 이탈이 발생하면 트랙이 완전히 만들어진 상태가 아니므로 복벽과 위가 붙어있지 않다. 이와 같은 경우는 위 내용물의 누출 및 복막염의 가능성이 커지므로 광범위 항생제의 사용이 필요하고, 도뇨관의 맹목적 삽입은 위장 내가 아닌 복강 내 비정상적인 위치에 있게 될 위험성이 있으므로 금지하고 있다[9,35].

위루관 주위 누출

위루관 주위 누출은 PEG의 1%-2%에서 발생하며, 대부분이 삽입한 이후 조기에 발생한다[36]. 누출의 위험요인에는 당뇨, 면역결핍, 영양결핍 등이 해당하며, 이 외에 위루에 발생한 육아조직(granulation tissue), 피부감염, 지나친 소독, 위산 증가, 고정자의 장력 증가 등이 영향을 줄 수 있다[37]. 누출이 발생한 경우, 임상의는 기저질환의 교정 여부를 확인하고, stoma powder (hydrocolloid powder)와 같은 흡수제를 이용하여 국소적 누출을 최소화하도록 한다[38]. 이러한 방법 이외에 zinc oxide 제제를 산분비억제제, 위장관운동촉진제와 함께 사용해 볼 수 있다. 육아종이 있는 경우는 아르곤 플라즈마 응고소작술(argon plasma coagulation)을 이용할 수 있다[30].

Buried bumper 증후군

Buried bumper 증후군은 위루술의 후기 합병증 중 하나로 위루관이 설치된 위점막의 허혈성 괴사로 내부 완충기가 원래 위치에서 이탈하여 위벽이나 복벽으로 이동되는 것을 말한다. 전체 위루술의 1%-4%에서 발생하는 것으로 보고되고 있으며[39,40], 위루관을 복벽에 지나치게 강하게 당겨서 고정하는 경우 발생한다. 내시경이나 컴퓨터 단층촬영으로 이동된 내부 고정자를 확인하여 진단할 수 있다. 임상적으로는 복통과 동반하여 위루관 주변으로 다량의 누출이 발생하거나, 주변 피부 조직이 붓고 빨갛게 변색이 되는 경우 의심해 볼 수 있다.

Buried bumper 증후군이 확인된 경우, 위루관을 제거하는 것이 원칙이다. 제거 이후 농양이나 복막염 등과 같은 합병증 여부에 따라 다른 위루관으로 교체를 하거나, 다른 위치에 위루관을 재삽입하는 것이 권장된다[41]. 내부 고정자가 쉽게 접히는 재료인 경우 위루관을 조심스럽게 당겨서 제거하고, 당겨서 제거가 안되는 경우 외과적 처치가 필요하다[11]. 농양과 같은 합병증이 동반되어 있을 때는 수술적으로 절개하여 제거한 후 광범위 항생제를 사용하도록 한다. Buried bumper 증후군은 심각한 합병증으로 예방을 위해서 위루술을 삽입한 시점으로부터 2주가 지나면 복벽으로부터 외부 고정자를 1-2 cm 정도의 거리를 두고 고정시키거나, 안쪽으로 위루관을 1 cm 가량 밀어넣고 360도 회전하고, 거즈를 외부 고정자 아래에 고정하거나 주기적으로 외부 위루관의 길이를 재는 것이 도움이 된다[9,40,41]. 외부 고정자는 3-5일 동안 복벽과 0.5 cm 정도 간격을 두고, 그 이후부터는 1 cm으로 간격을 늘리고, 7-10일이 지나고 나서 2-5 cm 정도 위루관을 넣고 빼는 술기를 통해서 내부 고정자와 위점막의 유착을 방지 하도록 한다[9].

출혈 및 천공

위루관 부위 출혈의 발생률은 0.3%로 굉장히 드물며, 대부분 좌위동맥(left gastric artery) 혹은 좌위대망동맥(gastroepiploic artery)의 손상으로 인해 발생한다[42]. 원인은 항응고제 복용, 해부학적 구조 변화가 가장 많으며, 이외에도 복벽이나 장간막의 큰 혈관의 손상으로 인해 발생할 수 있다. 위장 내부로의 출혈이나 피부로 스며나오는 출혈은 즉시 시술자가 인지할 수 있지만, 복강 내 혈관 손상으로 인한 출혈은 알기 힘든 경우가 있기 때문에 시술 이후 2시간 이내 동안은 저혈압, 빈맥과 같은 생체징후 이상의 발생 유무를 조심스럽게 살펴보아야 한다[43]. 출혈을 예방하기 위해서는 시술 전 앞에서 언급한 대로 출혈을 유발할 수 있는 약물의 조절이 필요하고 천자 부위로 복벽의 정중앙선은 피하도록 한다. 생체징후가 불안정해질 경우 컴퓨터 단층촬영 혈관조영술(CT angiography) 과 같은 영상학적 검사를 진행하여 복강 내 출혈 유무를 배제하여야 한다.

시술 후 기복증(pneumoperitoneum)은 40%-56%에서 발생하며 임상적으로 의미가 없는 경우가 대부분이다. 그러나, 일반 환자에서의 기복증은 그 자체로 수술적 중재술이 필요한 위험요인으로, 중환자를 대상으로 진행된 위루관 시술 이후 기복증이 확인되는 경우, 영양공급의 중단과 항생제 사용이 필요하다. 드물지만 중간에 낀 장기(대장, 소장, 장간막)의 손상(1%)으로 복막염이 진행되어 복통과 발열이 동반되고, 백혈구 증가 및 장마비가 함께 관찰될 수 있다[44].

위피부 누공(gastrocutaneous fistula)

위루는 위루관을 제거한지 24시간 이내부터 수일 이내에 닫힌다. 일부에서는 위루가 막히는데 수 주가 걸리며, 이는 위루관을 유지하던 기간과 관련이 깊다. 위피부 누공이 지속될 경우 수술을 대신하여 내시경적으로 through-the-scope clip, over-the-scope clip, 내시경 봉합(endoscopic suturing) 을 통해 해결할 수 있다[9].

영양공급 관련 합병증

PEG가 설치되고 난 이후 영양공급을 시행하게 된 뒤 발생할 수 있는 합병증에는 흡인, 설사, 영양재개증후군 등이 있다[30].

흡인은 위루관을 통한 영양공급을 받는 환자의 20%에서 발생할 수 있으며, 폐렴이나 호흡부전을 야기할 수 있다. 따라서, 많은 용량의 경장영양을 시행하기 앞서 조심스럽게 영양 공급을 시도해야 하며, 45도 침상머리 올림, 유문하경장영양으로 변경하는 방법을 위장관운동촉진제와 함께 사용해볼 수 있다[32].

설사는 영양공급 이후 15%-18%에서 발생하며, 항생제 사용과 Clostridioides difficile 감염, 고삼투성 약제, 영양액의 삼투압, 저알부민혈증 등으로 발생할 수 있다. 따라서, 설사를 조절하기 위해서는 복약에 대한 면밀한 검토가 필요하며, 그 밖에 경장영양액의 주입 속도를 감소시키거나, 필요시 영양액 변경을 통한 삼투압 조정 및 적절한 지사제의 사용이 필요할 수 있다[30].

영양재개증후군은 영양결핍환자에서 경장영양공급을 시작할 때 수 시간 내에 발생하는 전해질 감소 현상으로 심하면 부정맥, 심폐부전과 함께 사망에 이를 수 있다. 저인산혈증, 저칼륨혈증, 저마스네슘혈증같은 급격한 전해질 변화가 동반되기 때문에 예방하기 위해서 전해질 수치가 감소되기 이전에 미리 8 0 mEq의 칼륨 공급이 필요하며, 전체 필요한 열량의 25%만을 첫날에 공급하고 3-5일에 걸쳐서 증량할 것을 권장한다[27].

결 론

PEG는 경구 섭취가 어려운 환자에게 비교적 쉽고 효과적으로 영양공급을 제공할 수 있는 내시경 술기이다. 그러나, PEG를 시행하는 환자들의 대부분이 고령이거나 전신 상태가 좋지 않기 때문에, 합병증이 발생할 수 있다. 따라서, 시술은 적절한 적응증과 금기증에 따라 이뤄져야 하며, 환자의 안전과 합병증 예방을 위한 시술 전후 관리가 중요하다. 또한 위루술에 따른 다양한 합병증과 이에 대한 대처법에 대해 잘 숙지하고 있어야 하겠다.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no financial conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

None

Acknowledgements

None