장내미생물과 비만

Gut Microbiota and Obesity

Article information

Trans Abstract

Obesity is a global health concern associated with a wide range of diseases, including diabetes, metabolic syndrome, fatty liver, and cardiovascular conditions. Recent studies highlight the significant role of gut microbiota in obesity. Research indicates notable changes in the composition and diversity of gut microbiota in individuals diagnosed with obesity. The gut microbiota participate in energy metabolism, lipid synthesis, and regulation of inflammation and therefore play a key role in the pathogenesis of obesity. Therapeutic approaches based on the use of probiotics, prebiotics, Akkermansia muciniphila, and fecal microbiota transplantation have shown promise in animal studies as useful strategies against obesity and metabolic syndrome. However, further research is warranted to conclusively establish the specific strains, dosages, and mechanisms underlying the effectiveness of these novel strategies against obesity in humans.

서 론

비만은 당뇨나 대사증후군, 지방간 및 심혈관질환 등 여러 다양한 질환과 연관되어 있어 중요한 질환이다[1]. 2017년도에 전 세계적인 보고들을 분석한 논문에서는 인구의 1/3은 과체중, 10% 정도는 비만으로 보고하였다[2]. 국가 통계 포털에서 조사한 국내 유병률도 체질량지수 25 kg/m2 이상 인구를 기준으로 하였을 때, 성인에서 2012년 32.8%에서 2021년 37.2%로 증가하고 있다[3].

비만에는 여러가지 원인이 있긴 하지만, 장내미생물의 역할에 대한 연구들이 최근 증가하고 있다. 소화관에는 약 100조의 미생물이 살고 있으며, 4개의 문(Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria)이 많은 부분을 차지한다[4]. 건강한 상태에서 장 내 미생물은 인간과 조화롭게 공존하며, 필수영양소의 소화와 흡수를 돕고, 해로운 미생물을 방어하며 면역기능을 유지하는 데 관여한다[5]. 장내미생물은 염증반응이나 에너지 대사, 체중 항상성에 관여함으로써 비만과 관련되는 것으로 알려져 있다[6]. 본고에서는 최근 연구들을 바탕으로 비만 환자에서 장내미생물이 어떤 역할을 하는지 살펴보고, 비만 치료에 적응될 수 있는 가능성에 대해 논하고자 한다.

본 론

비만과 장내미생물의 관련성

비만과 장내미생물의 관련성이 증명되기 시작한 초기 연구는 무균마우스(germ-free mice)에서 장내미생물을 분석한 연구들이다. 같은 고지방식이를 섭취하게 하였을 때, 무균마우스는 일반 마우스와 달리 체중증가가 유도되지 않았고, 무균마우스에 비만 마우스의 대변을 이식하면 비만이 발생되는 것을 확인함으로써 장내미생물이 비만과 관련되어 있음을 시사하였다[7,8].

장내미생물 다양성의 감소는 장내미생물 불균형의 대표적인 변화로 비만이나 대사증후군에서도 다양성의 감소가 나타난다. 동물 연구에서는 고지방식이 유도 비만 마우스에서 정상 마우스보다 장내미생물 다양성의 감소가 나타나고, 고강도 운동 후 다양성이 회복된다고 보고하였다[9]. 비만 성인과 정상 체중 성인에서 장내미생물을 분석하였을 때, 비만 성인에서 미생물의 다양성이 감소되었다는 보고들이 있으며, 과체중 또는 비만 성인에서 대사증후군 진단 기준 하나 이상을 가지고 있는 것을 기준으로 나누어 장내미생물을 분석하였을 때도 대사이상 지표를 가지고 있는 성인에서 장내미생물의 α-diversity와 β-diversity가 감소되어 있음이 보고된 바 있다[10-13]. 비만 성인과 정상 체중 성인의 장내미생물의 유전자 수(gene count)를 비교한 연구에서는 유전자수가 낮은 경우 비만 유병률이 더 높았고, 낮은 유전자수는 인슐린 저항성이나 이상지질혈증, 전신 염증 등과 관련된 표지자 증가와 관련되어 있었고, 과체중 또는 비만 환자만을 대상으로 유전자수를 비교하였을 때에도 낮은 유전자 풍부도(gene richness)를 가지는 경우 대사 이상이나 염증이 증가되어 있었다[14,15].

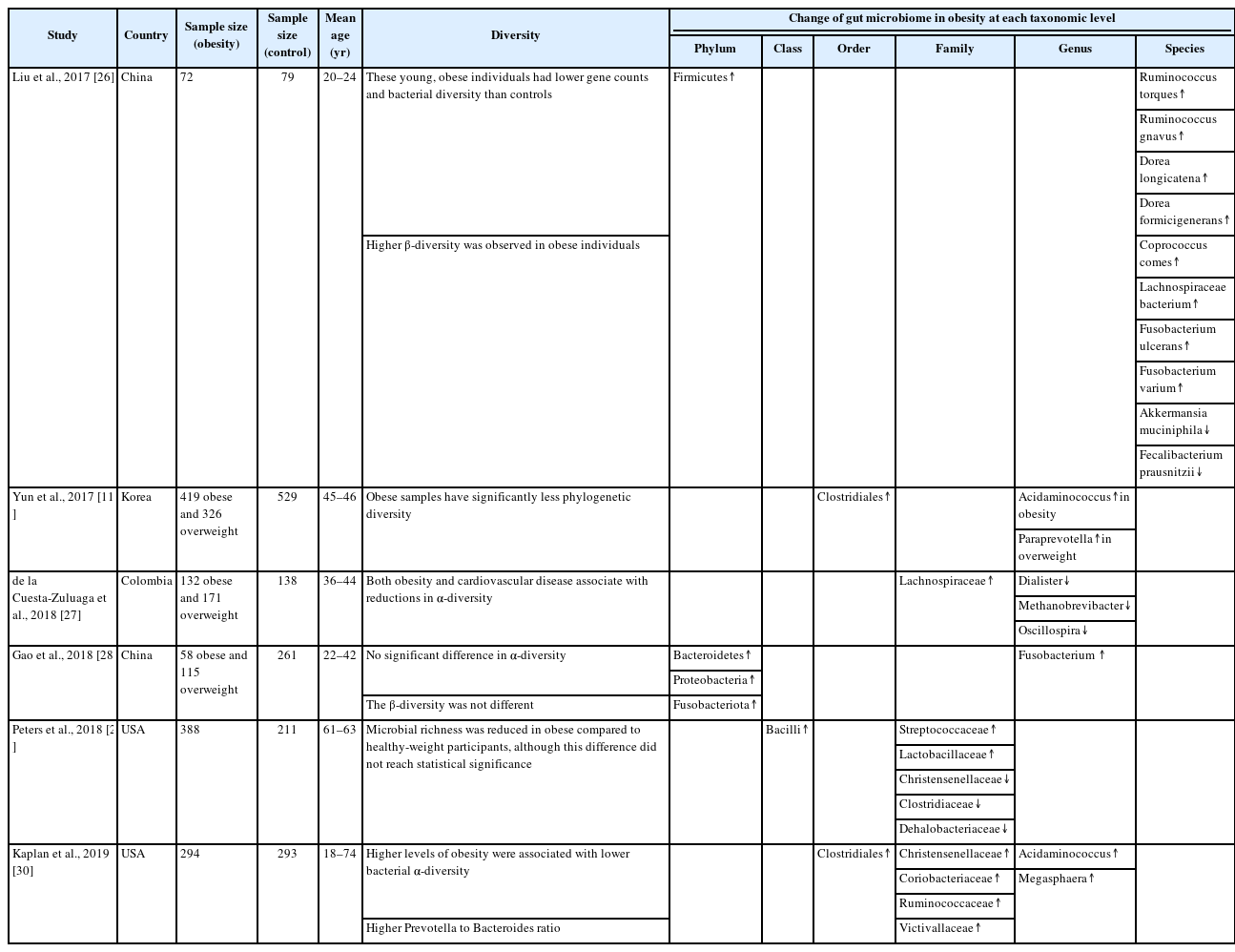

비만에서 장내미생물의 구성이 변한다는 연구들도 보고되고 있다. 정상인에 비해 비만 환자에서는 문(phylum) 수준에서 장내미생물을 분석하였을 때, Firmicutes가 증가하고, Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes 비율이 증가되어 있었고, 고지방식 유도 비만 쥐 실험에서도 유사한 결과를 보였다[16,17]. 그러나, 또 다른 연구들에서는 Firmicutes의 풍부도(abundance)와 Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes 비율이 비만인과 마른 성인에서 차이가 없음을 보고하여, 이런 소견을 비만의 특징적인 소견으로 단정할 수는 없겠다[18,19]. 비만과 관련된 장내미생물 종류에 관한 60개 연구에 대한 최근 메타분석에서는 Proteobacteria가 가장 일관되게 비만과 관련되어 있는 종류였다[20]. Proteus mirabilis와 Escherichia coli와 같은 Proteobacteria 문에 속하는 몇 개의 종은 위장관에서 염증을 유발하고, 이런 저등급염증(low-grade inflammation)은 인슐린 저항성 및 당뇨병을 포함한 대사 질환 발병의 위험인자로 알려져 있다[21,22]. 최근 연구들에서는 Akkermansia muciniphila(A. muciniphila)라는 종이 비만 및 대사 질환에서 저체중과 관련된 미생물로 보고되고 있는데, A. muciniphila는 장벽 기능을 조절하여 장벽방어기능을 개선하고 leaky gut에서 발생하는 염증을 조절하는 것으로 알려져 있다[23]. 그러나 같은 비만 성인에서도 먹는 음식이나 성별에 따라 증가 또는 감소하는 균주의 종류가 다르게 보고되고 있어 특정 균주와 비만과의 인과관계를 논하려면 추가적인 연구들이 필요하다[24,25]. 50명 이상의 비만 환자에서 대조군과 비교하여 장내미생물을 분석한 몇 개 연구들을 표로 정리하였다(Table 1) [11,26-30].

비만에서 장내미생물의 역할

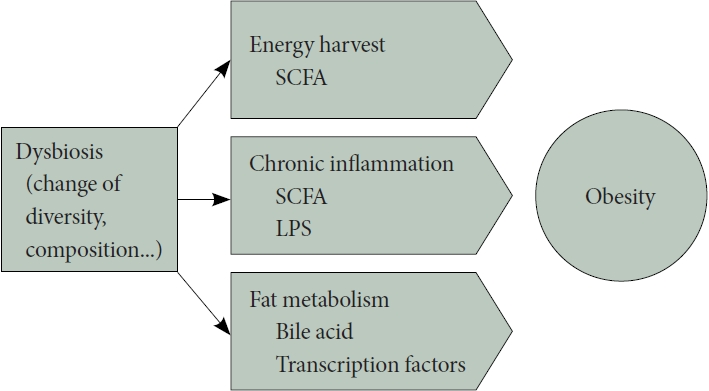

장내미생물 불균형은 인간의 에너지 대사를 조절하거나 만성염증 유발, 담즙산 및 지방대사에 관여함으로써 비만과 관련된다(Fig. 1).

Proposed mechanisms of gut microbiota involvement in obesity. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota, characterized by changes in diversity and composition, is implicated in obesity through various mechanisms. It affects host energy harvest via short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) produced through microbiota fermentation, triggers chronic inflammation through lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and SCFA actions, and contributes to obesity by regulating transcription factors related to lipid synthesis and storage and influencing bile acid metabolism.

에너지 대사

소장에서 소화되지 않는 탄수화물이나 식이성섬유가 장내 미생물에 의해 발효되면서 생기는 short-chain fatty acid(SCFA)는 대장 상피, 간 및 말초 조직을 포함한 다양한 신체 조직의 에너지원 역할을 한다[31]. 사람이 취득하는 에너지의 약 10%가 장내미생물의 발효로 얻어지며, 장내미생물은 인간의 ‘에너지 수확(energy harvest)’에 기여한다고 할 수 있다[32]. 무균마우스를 대상으로 한 연구에 따르면 동일한 식단에서, 균이 있는 마우스에 비해 무균마우스는 몸무게가 덜 나가고 더 많은 열량이 소변이나 대변으로 빠져나가는 것을 확인할 수 있어 같은 식이에서 더 적은 양의 에너지를 수확하는 것으로 생각되며, 이는 에너지 수확 및 숙주의 에너지 균형에서 장내미생물이 중요한 역할을 하고 있음을 시사한다[33]. 최근 몇 년 동안 SCFA는 장의 항상성과 에너지 대사에 대한 효과로 주목을 받고 있지만 비만에서의 역할은 논란의 여지가 있다. 비만이나 과체중에서 SCFA 생성과 관련된 유전자 및 SCFA 수치가 증가되어 있었다는 보고가 있는 반면[34], SCFA는 glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), peptide YY(PYY) 같은 호르몬을 분비함으로써 비만과 그 합병증을 방지하는 역할을 한다는 연구도 있다[35].

만성염증과 장벽방어기능

만성염증은 비만과 같은 대사질환에서 중요한 기전 중 하나이다. 최근 연구에서는 장내미생물이 여러 기전으로 염증을 조절한다는 근거들이 제시되고 있다[36]. 첫째로, 그람 음성 박테리아의 세포벽 구성 성분인 lipopolysaccharide (LPS)가 장벽을 통과하여 체내 전반적인 염증을 유발할 수 있다. LPS는 Toll-like receptor (TLR)-4를 활성화하고, TLR-4 신호 전달 변화는 nuclear factor-κB 및 IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α와 같은 염증성 사이토카인을 활성화시켜 지속적인 염증을 유발하고, 이는 인슐린 저항성을 유도하는 것으로 보고된다[37,38]. 둘째, 장내미생물의 대사산물이 숙주의 면역 시스템을 조절하는 역할을 한다. SCFA가 장내미생물과 염증의 연쇄 작용에서 중요한 역할을 하는 것으로 알려져 있다[39]. 셋째, 장내미생물은 인간의 장벽 기능을 유지하는 데 기여한다. 미생물은 숙주와 상호작용하여 다양한 대사 경로를 조절하고, 미생물의 조성이나 기능 변화는 장벽 기능 이상을 유발하고 대사 장애를 유도할 수 있다[40]. 이렇게, 장내미생물은 여러 가지 기전을 통해 염증을 조절하고, 대사성 내독소증(endotoxemia) 과 인슐린 저항성을 촉발할 수 있는 중요한 역할을 한다.

담즙산과 지방 대사

마우스를 이용한 실험논문에서는 장내미생물이 숙주의 장내 포도당 흡수와 혈액 내 포도당 농도를 증가시키고, 이를 통해 간에서 지방합성을 유도하는 두 가지 기본 전사 인자인 carbohydrate response element binding protein (ChREBP)과 sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP-1)의 발현 수준을 증가시키는 결과를 통해 장내미생물이 지방저장을 조절한다는 것을 보고하였다[41].

담즙산은 지방 소화 및 흡수에 중요한 역할을 하는데, 대부분의 담즙산은 재흡수되어 간으로 재순환되지만, 장내미생물에 의해 deconjugation되면 재흡수가 저하된다. Deconjugated bile acid는 장내미생물에 의해 2차 담즙산으로 대사되며, 대변으로의 배출이 용이해지게 된다. 담즙산의 대변 배출은 콜레스테롤의 주요 제거 경로 중 하나이며, 이로 인해 손실되는 담즙산은 콜레스테롤로부터 새롭게 합성되어 대체되어야 한다[42]. 지방 소화 역할 외에도 담즙산은 farnesoid X receptor (FXR)와 Takeda G-protein coupled bile acid receptor 5 (TGR5)에 결합함으로써 숙주의 대사를 조절하는 역할을 한다. 장내미생물에 의한 담즙산의 처리는 담즙산의 다양성을 증가시켜 수용체에 대한 다양한 작용을 가지게 한다. FXR은 중성지방의 합성이나 이용과 같은 지질 대사를 조절하기 때문에 장내미생물에 의한 담즙산 대사는 FXR과 상호작용을 통해 지질 대사에 영향을 주게 된다[43]. 또한, 담즙산은 골격 근육 및 갈색 지방 조직에서 에너지 소비를 촉진하는 역할을 하는 TGR5 활성을 통해서도 지질 대사를 조절한다[44].

장내미생물을 이용한 치료

프로바이오틱스

세계보건기구(WHO)에 따르면, 프로바이오틱스는 ‘충분한 양으로 투여될 때 숙주에 이로운 효과를 제공하는 살아있는 미생물’로 정의된다[45]. 최근 연구들에서는 대사 질환이나 염증, 비만을 개선하는 데 있어 프로바이오틱스의 효과에 대해 보고하고 있다. Bifidobacterium animalis는 비만 당뇨 마우스에서 지방량을 줄이고 포도당 대사를 개선하였고, 고지방 식이를 먹이는 쥐에서 Bifidobacterium을 투여하였을 때, 대사 증진 및 장벽방어기능 향상, 염증 감소 효과를 보고하였다[46,47]. 당뇨환자를 대상으로 한 무작위 임상시험에서는 Lactobacillus acidophilus 투여시 인슐린 민감도가 개선되는 것을 보여주었고, 비알콜성지방간 환자에서 Lactobacillus와 Bifidobacterium의 혼합 프로바이오틱스는 간수치 개선 효과를 보여주었다[48,49]. 프로바이오틱스의 효과에 대한 최근 메타분석에서는 비만 및 과체중 환자에서 체중 감소 효과와 체지방 감소 및 특정 심혈관 질환(CVD) 위험 지표 개선 효과를 보여주었지만, 포함된 연구의 균주 유형이 일관되지 않다는 한계점은 있다[50]. Lactobacillus의 체중 감소에 미치는 효과에 대한 동물 실험과 인간대상 연구를 포함한 메타분석에서는 Lactobacillus 종 및 숙주에 따라 체중 변화 패턴이 다를 수 있음을 보고하여 어떤 프로바이오틱스를 얼마동안 사용하는 것이 비만 개선에 효과적인지에 대해서는 추가적인 연구가 필요하다[51].

프리바이오틱스

프리바이오틱스는 ‘장내 미생물의 조성이나 활동에 이로운 변화를 줄 수 있는 선택적으로 발효되는 성분’으로 정의된다[52]. 락툴로스, 이눌린, 프룩토올리고당, 갈락토스 및 β-글루칸의 유도체가 대표적인 물질이며, 이들은 프로바이오틱스의 성장을 촉진하는 배지 역할을 한다[53]. 비만 및 대사 질환에서도 프리바이오틱스에 대한 연구들이 진행되었고, 비만 쥐에게 이눌린과 프룩토올리고당 투여시 Bifidobacterium과 Lactobacillus가 증가하고, PYY이나 GLP-1 같은 포만감 호르몬이 증가되었다[54]. 비만 또는 과체중 아동을 대상으로 한 무작위 대조 임상시험에서 올리고과당이 풍부한 이눌린을 투여하였을 때, 혈청 IL-6 수준과 체중이 유의하게 감소했고, 사람을 대상으로 하는 프리바이오틱스 투여에 대한 연구들의 체계적 고찰 결과, 프리바이오틱스 투여는 식후 고혈당 및 인슐린 분비를 저하시키고, 포만감을 증가시켰다[55,56]. 이런 연구들은 비만치료에서 프리바이오틱스의 역할에 대한 가능성을 보여준다.

A. muciniphila

A. muciniphila는 Verrucomicrobia문에 속하는 그람음성 혐기성 균으로 점액층을 분해하는 특징을 가지며, 건강한 성인의 장내미생물 중 3% 정도를 차지한다[57,58]. 비만이나 당뇨병 환자에서는 대변 내 A. muciniphila의 풍부도(abundance)가 감소하며, A. muciniphila의 풍부도는 쥐와 인간의 마른 체형과 상관관계가 있는 것으로 알려져 있다[59,60]. 쥐를 이용한 실험 연구들에서 A. muciniphila는 당뇨병, 비만, 염증성장 질환의 발병과 진행을 늦추는 것으로 보고된다[61]. 고지방식이 유도 비만 쥐에서 A. muciniphila를 투여하였을 때, 체지방 증가나 대사성 내독소증, 지방조직의 염증, 인슐린 저항성 등이 낮아지는 결과를 보였고, 당뇨병 쥐에서 A. muciniphila 유래 세포 외 소포체(extracellular vesicle)를 처리하였을 때 체중과 포도당 내성과 같은 대사 지표들이 개선되는 것을 확인하였다[60,62].

비만 또는 당뇨병 환자에서 A. muciniphila 투여의 효과를 조사한 무작위 대조 연구에서는 3개월 동안 경구로 생(living) 또는 저온살균된(pasteurized) A. muciniphila 제제를 투여했을 때, 두 제제 모두 인슐린 민감성 및 인슐린혈증, 총 콜레스테롤 수치를 개선시켰고, 저온살균제제 투여 시에는 체중과 체지방량, 엉덩이 둘레가 감소하는 효과를 보였다[63]. 이러한 연구들은 A. muciniphila가 비만과 대사질환과 관련되어 향후 비만치료에 유용하게 사용될 가능성을 보여주고 있다.

대변 이식

대변 이식(fecal microbiota transplantation, FMT)은 표준 치료에 반응하지 않는 재발성 Clostridium difficile 감염 치료에 효과적인 치료법으로 인정받아 사용되고 있다[64]. 변비나 과민성장증후군, 염증성 장질환 등 장내미생물의 불균형과 관련있다고 알려진 여러 질환에서 FMT의 효과에 대한 연구들이 발표되었으며, 비만이나 대사질환에서도 효과를 증명하려는 연구들이 진행되고 있다[65]. 고지방식 유도 비만 쥐에게 정상 쥐의 대변을 이식하면 체중이나 혈당 등의 지표가 개선되는 것이 보고되었다[66]. 대사증후군이 있는 비만인 9명을 대상으로 한 초기 연구에서는 마른 기증자로부터 FMT를 받은 후 인슐린 민감도가 향상되는 결과를 보였고, 다른 연구에서도 대사증후군이 있는 비만인이 마른 기증자의 대변 이식 후 6주째 인슐린 민감도와 HbA1C가 개선되는 것을 볼 수 있었으나, 18주에는 그 효과가 유지되지는 않았다[67,68]. 비만인을 대상으로 냉동캡슐을 이용하여 6주동안 매주 FMT를 시행한 연구에서는 체중이나 대사지표에서 유의미한 개선을 보여주지 못하여, 비만에서 FMT의 효과는 일관되게 입증되고 있지 않다[69]. 최근 9개 무작위 대조 연구에 대한 메타분석에서는 6주째 혈당이나 HbA1C, 인슐린 수치는 개선되었으나, 12주째는 개선효과가 보이지 않았고, 체중감소는 없었다고 보고하고 있다[70]. 이런 결과들을 고려할 때, FMT는 대사증후군의 지표 개선에 효과를 기대할 수 있으나 아직까지 많은 수의 환자를 대상으로 한 높은 수준의 연구가 드물고, 장기효과에 대한 근거는 약한 실정으로 추가적인 연구들이 필요하다.

결 론

비만은 전 세계적으로 심각한 사회경제적 영향을 끼치는 문제로 여겨지는 질환으로, 최근 연구들에 따르면 장내미생물은 비만의 여러가지 요인 중 하나로 생각되고 있다. 비만에 서는 장내 미생물의 구성과 다양성이 변화되며, 장내미생물은 숙주의 에너지 대사, 지질 합성 및 대사, 염증 조절 등에 관여하여 비만의 발병에 영향을 미친다. 프로바이오틱스나 프리바이오틱스, A. muciniphila와 같은 미생물을 이용한 치료, FMT 등은 동물 실험에서 비만이나 대사증후군 개선 효과를 보이고 있어 비만에 대한 미래의 치료 전략 중 하나로 여겨지지만, 아직 정확한 균종이나 기전에 따른 치료에 대한 근거는 충분하지 않아 추가적인 연구가 필요하다.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no financial conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

None

Acknowledgements

None