Clinical Outcomes of Transcatheter Arterial Embolization after Failed Endoscopic Intervention for Acute Non-Variceal Bleeding Associated with Benign Upper Gastrointestinal Diseases

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) is useful for management of uncontrolled upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding. We investigated clinical outcomes of TAE for non-variceal bleeding from benign UGI diseases uncontrolled with endoscopic intervention.

Methods

This retrospective study performed between 2017 and 2021 across four South Korean hospitals. Ninety-two patients (72 men, 20 women) who underwent angiography were included after the failure of endoscopic intervention for benign UGI disease- induced acute non-variceal bleeding. We investigated the factors associated with endoscopic hemostasis failure, the technical success rate of TAE, and post-TAE 30-day rebleeding and mortality rates.

Results

The stomach (52/92, 56.5%) and duodenum (40/92, 43.5%) were the most common sites of bleeding. Failure of endoscopic procedures was attributable to peptic ulcer disease (81/92, 88.0%), followed by pseudo-aneurysm (5/92, 5.4%), and angiodysplasia (2/92, 2.2%). Massive bleeding that interfered with optimal visualization of the endoscopic field was the most common indication for TAE both in the stomach (22/52, 42.3%) and duodenum (14/40, 35.0%). Targeted TAE, empirical TAE, and exclusive arteriography were performed in 77 (83.7%), nine (9.8%), and six patients (6.5%), respectively. The technical success rate, the post-TAE 30-day rebleeding rate, and the overall mortality rate were 100%, 22.1%, and 5.8%, respectively. On multivariate analysis, coagulopathy (OR, 5.66; 95% CI, 1.71~18.74; P=0.005) and empirical embolization (OR, 5.71; 95% CI, 1.14~28.65; P=0.034) were independent risk factors for post-TAE 30-day rebleeding episodes.

Conclusions

TAE may be useful for acute non-variceal UGI bleeding. Targeted embolization and correction of coagulopathy can improve clinical outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding includes both variceal and non-variceal bleeding. Nonvariceal bleeding includes bleeding associated with peptic ulcers, esophageal-gastric junction mucosal lacerations, and vascular dysplasia [1,2]. Acute nonvariceal UGI bleeding requires immediate evaluation and the consideration of multifaceted treatment. Although treatment of nonvariceal UGI bleeding with high-dose proton pump inhibitors and endoscopic hemostasis is a preferred approach, rebleeding occurs in 10~20% of the cases [3]. In patients with multiple comorbidities, the mortality rate may increase to 30% due to refractory bleeding [3,4]. Therefore, if hemostasis is not achieved using drugs or endoscopic procedures, additional treatment, such as radiological vascular embolization or surgery, is needed. Surgery is the traditional treatment of choice after endoscopic hemostasis failure, but it is more invasive than vascular embolization and carries a higher risk of complications [5]. Angiography and vascular embolization are non-surgical methods that can be performed in patients with poor general body condition. After the development of embolics and interventional radiology technology, these approaches became the preferred treatment for acute gastrointestinal bleeding [6,7]. However, there is little information regarding the clinical circumstances that result in angiography and vascular embolization after the failure of endoscopic hemostasis in acute nonvariceal UGI bleeding patients.

The purpose of this multicenter study was to identify the clinical situations of angiography and vascular embolization performed in Korea. We also analyzed the clinical outcomes, such as the technical success, rebleeding, and 30-day mortality rates. The factors affecting the occurrence of rebleeding within 30 days of vascular embolization were also investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study subjects

This study retrospectively analyzed the medical records of patients who underwent angiography and embolization for acute nonvariceal UGI bleeding, after the failure of UGI endoscopic hemostasis, at Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, Keimyung University Dongsan Hospital, Yangsan Pusan National University Hospital, and Myongji Hospital between January 2017 and December 2021. Eligible patients were identified by the endoscopy and radiology intervention team of the departments of Gastroenterology and Radiology. A total of 92 patients with acute nonvariceal UGI bleeding were analyzed. Patients were excluded if they had bleeding from the esophagus or gastricvarices. Patients with cancer bleeding were also excluded. This study was approved by the Institutional Bioethics Committee of Myongji Hospital (No. 2022-03-027).

2. UGI endoscopy

UGI endoscopy was first performed in the presence of bleeding symptoms, including vomiting, black stool, and bloody stool, and decreased hemoglobin levels. Abdominal CT was performed if the bleeding continued due to unsuccessful hemostasis or if the source of the bleeding could not be clearly identified due to severe bleeding.

3. Angiography and embolization methods

Angiography was performed, through the femoral artery, to identify bleeding sites in the celiac, superior mesenteric, and splenic arteries. Targeted embolization was performed when angiography confirmed outflow of contrast agent or if there were indirect signs of bleeding, including pseudoaneurysm formation, vascular irregularities, vascular blockage, increased numbers of blood vessels in an area of neovascularization, and dilated arterioles. Empiric embolization was performed in the absence of angiographically confirmed bleeding lesions if the UGI endoscopy and abdominal CT findings were indicative of bleeding.

Each embolic agent, a fine coil (Tornado or MicroNester; Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA), Gelatin Sponge (Spongostan; Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA and EG-GEL; Engain, Seongnam, Korea), N-butyl-cyanoacrylate glue (Glubran; GEM SRL, Viareggio, Italy and Histoacryl®; B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany), Pamiray300 (Dongkook Pharm., Seoul, Korea and Therapex; Montreal, Canada), or polyvinyl alcohol particles (Contour; Boston Scientific, Watertown, MA, USA and Bearing nsPVA; Merit Medical System, South Jordan, UT, USA) was used alone or in combination with other agents. Angiography and vascular embolization were performed by 19 radiologists with 3~22 years of experience on interventional radiology procedures.

4. Clinical course

The enrolled patients’ medical records, upper intestinal tract endoscopy results, blood tests, CT findings, vital signs, angiography and vascular embolization images, and results were checked. The causes of UGI bleeding, endoscopic hemostasis failure, and reasons for angiography were investigated. The success of the vascular embolization (hemostasis) was confirmed.

UGI bleeding was defined as bleeding that occurred proximal to the ligament of Treitz. Technical success was defined as occlusion of the blood vessels associated with the bleeding site, cessation of contract agent leakage, or absence of pseudoaneurysm formation after embolization. Rebleeding was defined as the recurrence of clinical bleeding symptoms, such as vomiting, black stools, or bloody stools, within 30 days of the embolization, accompanied by a ≥2.0 g/dL decrease in hemoglobin levels. Among the potential vascular embolization-related complications, gastric ischemic damage was confirmed by endoscopic evidence of ischemic damage centered on the mucosal layer of the UGI tract; splenic infarction was confirmed by decreased contrast enhancement or loss of abdominal CT findings. Coagulopathy was defined as a prothrombin international normalized ratio ≥1.5, partial thromboplastin time >45 seconds, or a platelet count <80,000/mL [8]. Shock was defined as a systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg. Risk scores were determined using AIMS-65 and Glasgow-Blatchford scores for patients with nonvariceal UGI bleeding [9,10].

5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows software (version 21.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were analyzed using student's t-test or the Kruskal-Wallis test to determine mean±standard deviations and medians (minimum-maximum). Categorical variables, expressed as frequencies (%), were analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. To identify the independent factors associated with rebleeding within 30 days of vascular embolization, variables with a P-value <0.10 in a univariate analysis were included in a multivariate logistic regression model. If the P-value was less than 0.05, it was judged to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

1. Demographic characteristics of patients

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the 92 patients who were enrolled in this study. The average age of the patients was 66.1 years and 72 (78.3%) of the patients were males. Among the patients, 38 (41.3%) had hypertension, 25 (27.2%) had diabetes, and 18 (19.6%) had histories of peptic ulcers. Forty-three (46.7%) had two or more chronic underlying diseases. The mean hemoglobin and blood urea nitrogen levels were 6.6±1.4 g/dL and 55.7±24.8 mg/dL, respectively. Antiplatelet drugs were taken by 18 patients (19.6%) and six (6.5%) were on anticoagulant therapy. There were 88 patients (95.7%) with bleeding symptoms (e.g., vomiting, black stool, bloody stool) and the remaining four patients (4.3%) showed decreased hemoglobin levels without significant signs of bleeding. In those four patients, bleeding lesions were subsequently confirmed using UGI endoscopy.

2. Etiology of endoscopic treatment failure and reasons for angiography

The endoscopically determined cause of the bleeding that led to angiography was peptic ulcers in 81 patients (88.0%) and pseudoaneurysms in five (5.4%). Less frequent causes included vascular dysplasia, dieulafoy lesion, duodenal diverticulum, bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection of the stomach, and iatrogenic damage during endoscopy (Table 1). When the bleeding sites were identified in the stomach or duodenum, the most common reason for performing angiography was difficult visualization of the bleeding lesions because of massive bleeding (Fig. 1). When the Forrest classification was used to classify the peptic ulcer bleeding, the most common form of bleeding in the stomach was Forrest lla (25 patients, 48.1%) and the most common form of bleeding in the duodenum was Forrest lb (13 patients, 32.5%). Most frequently used endoscopic hemostasis method was a combination of thermal coagulation and endoscopic clip hemostasis (14 patients, 15.2%). Before angiography was performed, 63 patients (68.5%) underwent both UGI endoscopy and abdominal CT; 26 (28.3%) had contrast agent leakage confirmed during their abdominal CT.

3. Timing and method of angiography and embolization

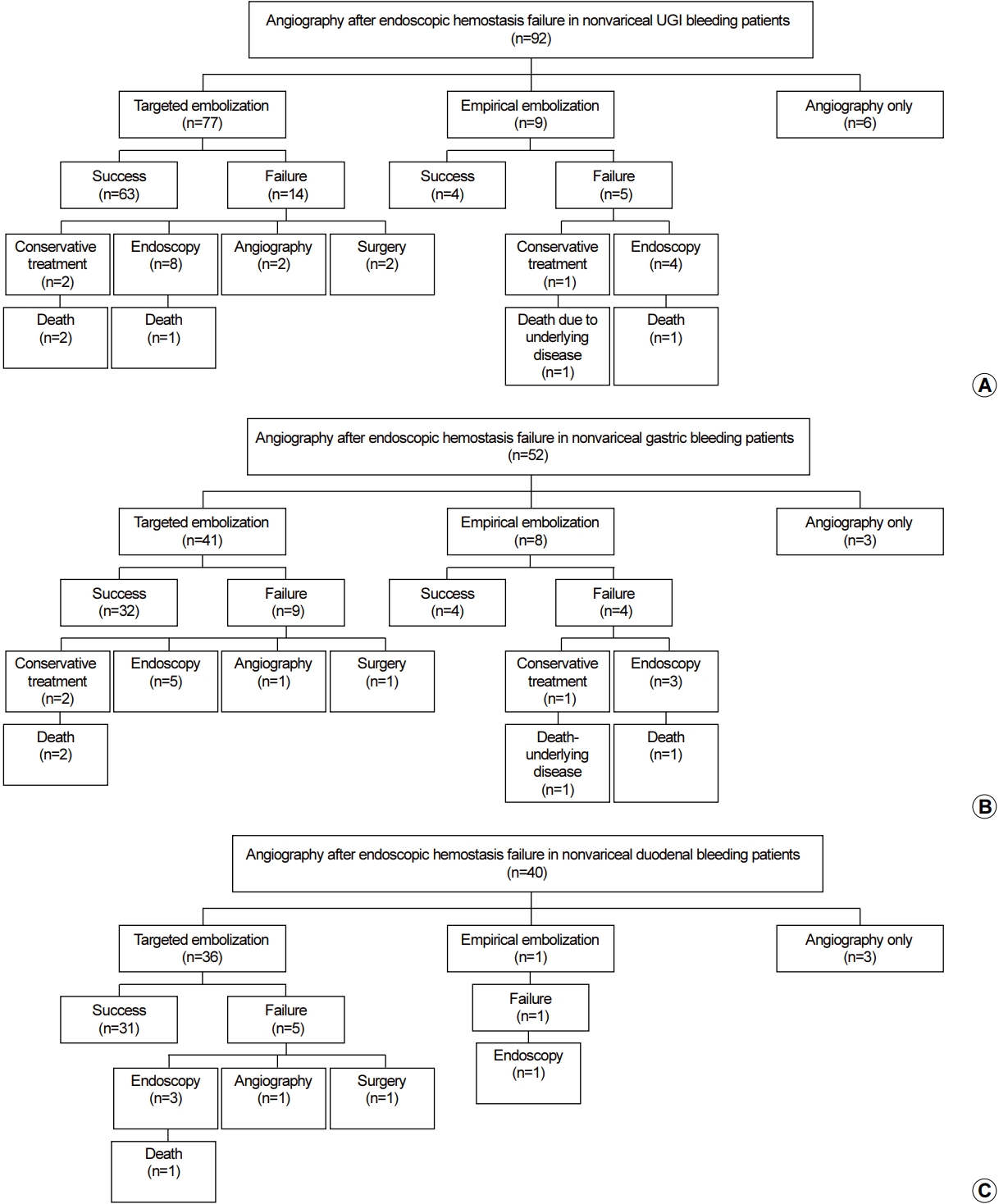

Of the 92 patients who underwent angiography, 77 underwent selective embolization when hemorrhagic lesions were identified. In nine of the 15 patients with bleeding lesions that could not be identified using angiography, empirical embolization was performed at the suspected bleeding site, according to clinical judgment. In six patients, angiographic examinations were performed without embolization (Fig. 2A). The bleeding site was classified as being in the stomach or duodenum, and angiography was performed for embolization. Of the 52 patients who underwent angiography for gastric bleeding, selective embolization was performed in 41 patients and empiric embolization in eight patients (Fig. 2B). Of the 40 patients with duodenal bleeding who underwent angiography after UGI endoscopic hemostasis failure, selective embolization was performed in 36 patients and empiric embolization was performed in one patient (Fig. 2C).

(A) Results of angiography after failed endoscopic hemostasis performed for nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. (B) Results of angiography after failed endoscopic hemostasis performed for nonvariceal gastric bleeding. (C) Results of angiography after failed endoscopic hemostasis performed for nonvariceal duodenal bleeding. UGI, upper gastrointestinal.

Angiography was performed within 12 hours after endoscopic hemostasis failure in 43 patients (46.7%), within 12~24 hours in 22 patients (23.9%), and after 24 hours in 27 patients (29.3%) (Table 2). Vascular embolization was performed on the gastroduodenal artery in 30 patients (32.6%) and on the left gastric artery in 29 patients (31.5%). Six patients (6.5%) had embolization on two blood vessels and three (3.3%) had embolization on three or more blood vessels. Of the vascular embolization agents used, 45 patients (48.9%) were treated using only gelatin sponges, 17 (18.5%) were treated with only N-butyl cyanoacrylate, and 14 (17.4%) were treated with two embolic agents.

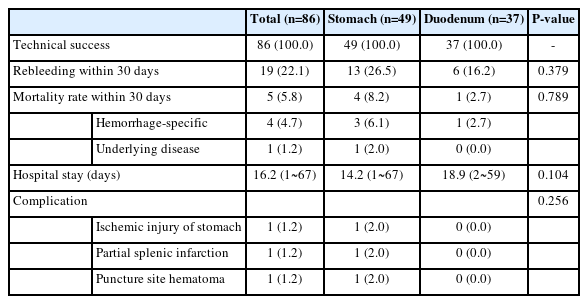

4. Success rate and clinical course following vascular embolization

Except for six patients who underwent angiography, without vascular embolization, the technical success rate of the vascular embolizations in the remaining 86 patients was 100%. A total of 19 patients (22.1%) demonstrated rebleeding within 30 days of the vascular embolization and five (5.8%) died within the initial 30-day period (Table 3). The 30-day rebleeding rates for patients undergoing vascular embolization of gastric and duodenal bleeding sites were 26.5% (13/49 patients) and 16.2% (6/37 patients), respectively. Although 30-day rebleeding occurred more frequently in gastric bleeding patients than in duodenal bleeding patients, the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.379). Of the 19 patients who had rebleeding within 30 days after vascular embolization, three patients received conservative treatment, 12 received endoscopic hemostasis again, two underwent embolization again, and two were treated surgically (Fig. 2A). The median duration of hospitalization for the 81 patients was 16.2 days (range, 1~67) after excluding expired patients.

5. Vascular embolization complications

The incidence of complications associated with vascular embolization was 3.5% (3/86). All complications occurred after embolization of gastric bleeding lesions (Table 3). The complications included gastric ischemic injury, partial splenic infarction, and hematoma at the catheter insertion site.

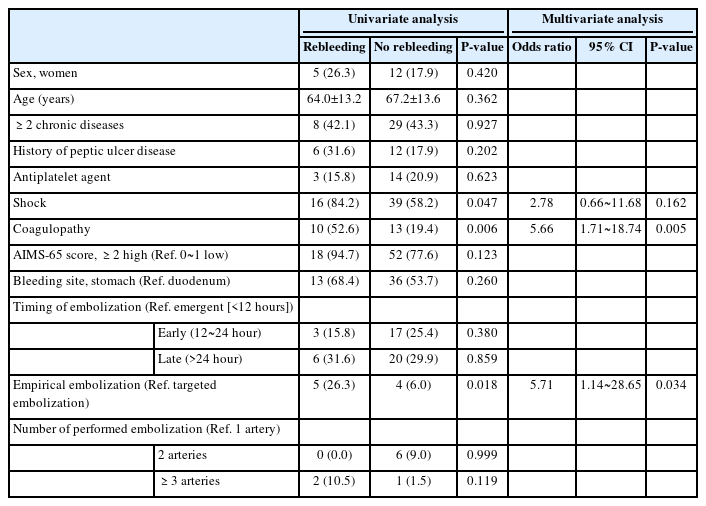

6. Risk factors for rebleeding within 30 days after vascular embolization

On multivariate logistic regression analysis, risk factors for rebleeding within 30 days after vascular embolization were coagulation disorders (OR, 5.66; 95% CI, 1.71~18.74; P=0.005) and empiric embolization (OR, 5.71; 95% CI, 1.14~28.65; P=0.034). Both factors were independent risk factors for the occurrence of rebleeding within 30 days after vascular embolization (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

This study is the first multicenter study in Korea that analyzed the use of angiography and embolization after UGI endoscopic hemostasis for acute nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding. Clinical performance of vascular embolization was also evaluated. In cases of acute nonvariceal gastrointestinal tract bleeding, the causes of endoscopic hemostasis failure were analyzed after classifying the cases into gastric and duodenal bleeding. The most common reason for endoscopic hemostasis failure was associated with difficult visualization of the bleeding source because of excessive bleeding from the gastric or duodenal ulcer disease. In this study, the peptic ulcer bleeding foci that led to vascular embolization after endoscopic hemostasis failure were analyzed using the Forrest classification. Forrest IIa was most common in gastric ulcers and Forrest Ib was most common in duodenal ulcers. Forrest IIb ulcers were associated with disagreements regarding the need for endoscopic hemostasis (four cases each of gastric and duodenal ulcers). None of the cases corresponded to Forrest IIc and III ulcers that did not require endoscopic hemostasis. Rebleeding rates are approximately 55% for Forrest Ia-Ib ulcers, 43% for Forrest IIa, 25% for Forrest IIb, <10% for Forrest IIc, and <5% for Forrest III ulcers [11-13]. Because we analyzed patients who underwent vascular embolization after endoscopic hemostasis failure, the results differed from those typically associated with the Forrest classification which is used as an indicator of rebleeding risk during endoscopy. Other than the endoscopic bleeding activity classification, ulcer sizes >2 cm are suggested to increase the risk of rebleeding after endoscopic hemostasis [14].

In previous studies, the rate of detection of hemorrhagic lesions during angiography is in the range of 45.9~86.4% [15-17]. In this study, 83.6% of cases that underwent selective embolization for bleeding lesions were identified using angiography. When including the empirically embolized cases without identifying the bleeding focus, 93.5% of the bleeding lesions were identified during angiography. This is because patients in this study underwent angiography after detecting UGI bleeding using endoscopy. Conversely, in the past, angiography was performed regardless of UGI endoscopic findings in patients showing bleeding signs.

Worldwide, radiological vascular intervention is becoming a common alternative treatment for refractory nonvariceal UGI bleeding [6,18]. In this study, the technical success rate of vascular embolization was excellent, but the rebleeding and 30-day mortality rates after vascular embolization were 22.1% and 5.8%, respectively. The risks of rebleeding (26.5% vs. 16.2%) and 30-day mortality (8.2% vs. 2.7%) were higher for gastric lesions than for duodenal lesions, respectively; however, the difference was not statistically significant. Previous studies showed similar results with our study regarding technical success rates for vascular embolization of acute nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding of 98~100%, rebleeding within 30 days rates of 15.7~39%, and 30-day mortality rates of 4~22.4% [18-21]. Previous studies on vascular embolization performance for gastric and duodenal bleeding also showed higher technical success (100% vs. 97~100%), 30-day rebleeding (20.6~35% vs. 37.8~41%), and 30-day mortality (17.6~29% vs. 26.9~31%) rates for gastric lesions than for duodenal lesions, respectively. Although there was no statistical significance in duodenal bleeding compared to the gastric bleeding, the clinical performance of vascular embolization was relatively poor [18,20]. This is because, in previous studies, about 60% of the cases of UGI endoscopy were performed before vascular embolization. Vascular embolization was performed without identifying gastric or duodenal bleeding focus in those previous studies.

A multivariate analysis of the occurrence of rebleeding within 30 days of vascular embolization confirmed that coagulation disorders and empiric embolization were significant contributing factors. Previous studies also indicated that coagulation disorders are significantly associated with an increased risk of rebleeding after vascular embolization [8,17,22]. In patients with UGI bleeding, checking for hematological abnormalities before and after vascular embolization is important, as is actively corrected through blood transfusions. Arrayeh et al. [23] reported that empiric vascular embolization is helpful for reducing the incidence of rebleeding for gastric bleeding cases but not for gastric bleeding cases. In a national study, of patients with upper, middle, and lower gastrointestinal bleeding reported lower clinical success rates (44.8% vs. 67.9%) for empiric vascular embolization than for selective vascular embolization [16]. To reduce rebleeding after empiric vascular embolization, performing the embolization after confirming the etiology and location of the bleeding, might be helpful using preliminary examinations such as UGI endsocopy.

Complications associated with vascular embolization occur in 0~18.9% of cases. Further, because the UGI tract has collateral blood circulation, the frequency of complications is lower than following embolization in the central or lower gastrointestinal tract [7,17,18]. In this study, a total of three complications (one gastric ischemic injury, one partial splenic infarction, and one catheter insertion site hematoma) occurred after vascular embolization. All occurred after vascular embolization for gastric bleeding, and the patients recovered after conservative treatment.

This study has some limitations. First, this study was based on a retrospective analysis of medical records; therefore, there is a possibility of selection bias. Further, patients did not necessarily receive similar examinations and treatment owing to the multicenter nature of the study. Second, because the experience and skills of the endoscopists and interventional radiologists varied, follow-up studies are needed to generalize the findings. Third, among patients with acute nonvariceal UGI bleeding, patients with malignant upper intestinal bleeding (e.g., gastric cancer) were excluded. This was because, unlike benign nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding, patients with malignant UGI bleeding may also have had direct invasion of blood vessels, severe mucositis, or tissue necrosis due to chemotherapy or radiation. Hence, there is a large difference in hemostatic treatment methods and the risk of rebleeding [24]. Fourth, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is a major cause of peptic ulcers and requires appropriate diagnostic testing and bacteriostatic treatment to prevent recurrence and reduce complications. In this study, because of the difficulties associated with H. pylori testing, such as possible false negatives, shock, and coagulation disorders, only 26 patients (28.3%) were tested. Therefore, the presence of H. pylori infection was not analyzed in this study. Despite these limitations, this multicenter study has value because it involved advanced general and secondary general hospitals in various regions of Korea. Moreover, the study analyzed the actual clinical situations in which angiography and vascular embolization were performed after UGI bleeding. Moreover, the clinical results of vascular embolization were analyzed more than 30 days later after the procedure.

In summary, the causes of acute, nonvariceal UGI bleeding in patients who underwent angiography and vascular embolization following endoscopic hemostasis failure in Korea, were peptic ulcers and pseudoaneurysms. The technical success rate for vascular embolization in these patients was excellent, but rebleeding within 30 days of the procedure occurred in approximately 22% of cases. Since coagulation disorders and empirical embolization were significant factors associated with the occurrence of rebleeding, confirming and correcting coagulation disorders are necessary. Moreover, identifying the etiology of the bleeding (e.g., using UGI endoscopy to find the bleeding lesions) would help to ensure more cases of selective embolization and maximize the number of longer-term successes.

Notes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material 1. Korean translation of the article is available from https://doi.org/10.7704/kjhugr.2022.0054.