산분비억제제

Acid Suppressive Drugs

Article information

Trans Abstract

Histamine H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) suppress gastric acid production by blocking H2 receptors in parietal cells. Studies have shown that proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are superior to H2RAs as a treatment for acid-related disorders, such as peptic ulcer disease (PUD) and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). PPIs reduce gastric acid production by irreversibly inhibiting the H+/K+ ATPase pump, and they also increase gastric emptying. Although PPIs have differing pharmacokinetic properties, each PPI is effective in managing GERD and PUDs. However, PPIs have some limitations, including short plasma half-lives, breakthrough symptoms (especially at night), meal-associated dosing, and concerns associated with long-term PPI use. Potassium-competitive acid blockers (P-CABs) provide more rapid and profound suppression of intragastric acidity than PPIs. P-CABs are non-inferior to lansoprazole in healing erosive esophagitis and peptic ulcers, and may also be effective in improving symptoms in patients with non-erosive reflux disease. Acid suppressive drugs are the most commonly used drugs in clinical practice, and it is necessary to understand the pharmacological properties and adverse effects of each drug.

서 론

다양한 상부위장관 질환에서 그 병태생리의 중심에 위산 분비의 증가가 있다. 과거에는 위산 분비를 억제하기 위해 H2 수용체 길항제(histamine H2-receptor antagonist)가 사용되었으며, 오메프라졸(omeprazole)을 필두로 양성자펌프억제제(proton pump inhibitor, PPI)가 등장한 이후 소화성 궤양이나 위식도 역류 질환(gastroesophageal reflux disease, GERD)의 치료에 획기적인 전기가 마련되었다. 최근에는 칼륨 경쟁적 산 억제제(potassium competitive acid blocker, P-CAB)가 임상에서 PPI를 대체하며 많이 사용되고 있다. 본고에서는 최근까지의 연구 결과를 바탕으로 현재 임상에서 사용되고 있는 다양한 산 분비 억제제(acid-suppressive drugs)의 작용기전, 약리학적 특성, 임상적 이용에 대해 정리해 보고자 한다.

본 론

1. H2 수용체 길항제

1) 작용기전 및 약리학적 특성

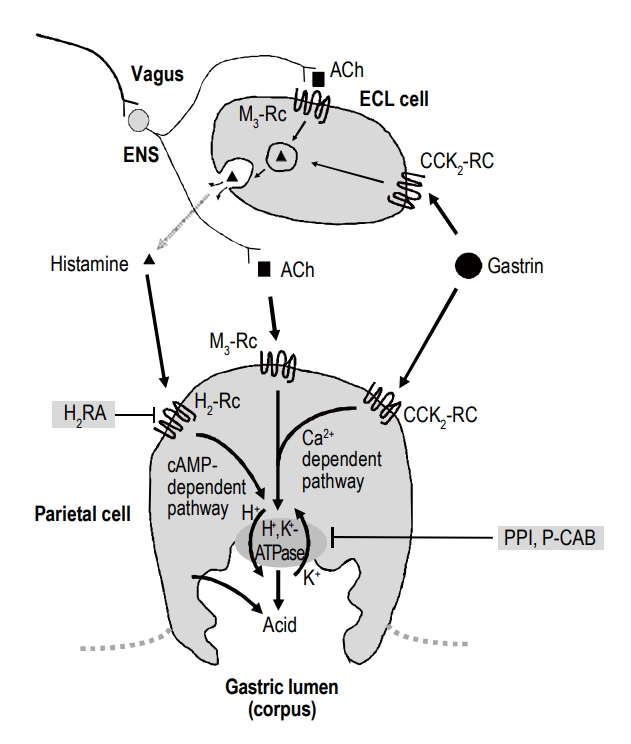

H2 수용체 길항제의 작용을 이해하려면, 우선 위 벽세포(parietal cell)에서 이루어지는 위산 분비 조절 기전에 대한 이해가 필요하다(Fig. 1). 벽세포의 위산 분비 조절은 다음과 같다. ① 미주신경(vagus nerve)의 조절을 받는 장신경계(enteric nervous system)의 신경 말단에서 분비되는 아세틸콜린(acetylcholine)이 벽세포 세포막의 무스카린 M3 수용체에 결합하거나, ② 전정부 G세포에서 분비되는 가스트린(gastrin)이 cholesystokinin-2 수용체에 결합하거나, ③ 장크롬친화세포(enterochromaffin-like cell)에서 분비된 히스타민(histamine)이 H2 수용체에 결합하여 위산 분비를 조절하게 된다[1,2]. 히스타민은 벽세포의 H2 수용체에 결합하여 세포 내 cyclic adenosine monophosphate의 농도를 높이고 protein kinase A 효소를 활성화시킨다. 활성화된 protein kinase A는 양성자펌프(proton pump, H+, K+-ATPase)를 세포질 내 소포(tubulovesicle)에서 세포막으로 이동시키는 데 관여하는 세포골격 단백질을 인산화(phosphorylation)시켜 비활성화 상태로 있던 양성자펌프를 활성화시킨다. 세포막으로 이동된 활성화된 양성자펌프는 세포 내 양성자와 세포 외 칼륨 이온을 교환하면서 위산을 분비한다.

Three pathways of proton pump inhibition. Ach, acetylcholine; Rc; receptor; ECL, enterochromaffin-like; ENS, enteric nervous system; CCK, cholecystokinin; H2RA, histamine-2 receptor antagonist; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; Ca, calcium; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; P-CAB, potassium-competitive acid blocker.

H2 수용체 길항제는 히스타민과 경쟁적으로 H2 수용체에 결합하여 위산 분비를 억제한다. H2 수용체 길항제는 경구 투여 후 1~3시간에 혈중 농도 최고치에 이르고, 뇌혈류장벽(blood brain barrier)을 통과할 수 있으며 전신에 분포한다. 우선 약력학적(pharmacokinetics) 특징을 보면 H2 수용체 길항제 중 시메티딘(cimetidine), 파모티딘(famotidine), 라니티딘(ranitidine)의 생체 이용률(bioavailability)은 간에서 1차 대사를 거치면서 35~60%까지 감소된다. 한편 니자티딘(nizatidine)은 간 대사를 거치지 않으므로 생체 이용률이 높으며, 90%가 소변으로 배출되기 때문에 약력학적으로는 신기능의 영향을 받는다. 일부 H2 수용체 길항제는 간 cytochrome P450에 의해 다른 약물과 상호작용이 발생할 수 있어 시메티딘과 라니티딘의 경우 같은 효소계에 의해 대사되는 다른 약물 농도에 영향을 줄 수 있는 반면, 파모티딘과 니자티딘은 cytochrome P450계 효소의 친화도가 낮아 다른 약물과의 상호작용이 거의 없다. 라퓨티딘 (Lafutidine)은 pyridine 환을 모핵으로 한 H2 수용체 길항제와 달리 새로운 화학 구조를 가진 H2 수용체 길항제이며[3], H2 수용체 차단 효과뿐 아니라 점막 혈류 증가를 통한 방어인자 증강 작용 효과도 가지고 있다. 각 약제의 효능(potency)을 비교하면 니자티딘과 라니티딘은 시메티딘에 비해 위산 억제 효과가 4배 높고, 파모티딘은 시메티딘보다는 20배, 라니티딘보다는 7.5배 위산 억제 효과가 높다고 보고되었다[2].

H2 수용체 길항제는 벽세포의 H2 수용체에 매우 선택적으로 결합하기 때문에 다른 히스타민 수용체에는 거의 작용을 하지 않는다[2]. 그럼에도 불구하고 H2 수용체 길항제와 연관된 여러 부작용들이 보고되고 있다[2]. H2 수용체 길항제의 비교적 흔한 부작용으로는 설사, 두통, 어지럼증, 졸림, 변비 등이 있다. 시메티딘을 장기 복용하면 여성형 유방(gynecomastia)이 0.3~4%에서 발생할 수 있다. 또한 약제를 중단하면 야간 산 분비 증가(rebound nocturnal acid hypersecretion)가 발생한다[4]. H2 수용체 길항제나 PPI 투여로 인한 위산 분비 억제는 철분의 흡수를 저하시킨다. 위산은 비헴철(non-heme iron)의 흡수를 촉진하고, 제1철(ferrous form)을 더 흡수가 잘되는 제2철(ferric form)로 전환시키기 때문이다[5,6]. 따라서 위산 억제 치료는 잠재적으로 철 결핍을 유발할 수 있고 철분제제 치료를 방해할 수 있다[2].

임상적으로 중요한 특성 중 하나로 H2 수용체 길항제를 2주 이상 장기간 투여할 경우 내성(tachyphylaxis)이 발생한다[7]. 무작위 위약-대조군 연구에서 파모티딘 40 mg을 저녁 식후 1회 복용 시에 첫날 24시간 위 내 평균 pH 3.2에서 28일째에는 1.9까지 감소하였고, 라니티딘 300 mg을 하루 네 번 복용하였을 때 첫날 24시간 위 내 평균 pH 5.0에서 7일째 3.0, 라니티딘 300 mg을 하루 세 번 복용하였을 때 24시간 위 내 평균 pH 4.3에서 14일째 2.4까지 감소하였다[7]. 이처럼 H2 수용체 길항제 약물 내성이 발생하는 기전은 혈중 가스트린(gastrin) 농도와 연관이 있다. H2 수용체 길항제는 다른 산 분비 억제제와 같이 위 pH를 상승시키므로, 저산증에 반응하여 혈중 가스트린 농도의 상승을 초래하게 되므로 위산 분비 억제 효과가 반감된다. 혈중 가스트린 농도의 상승은 간접적으로 장크롬친화 세포로부터의 히스타민 분비를 증가시켜 위산을 분비하도록 할 뿐 아니라 직접적으로 벽세포의 가스트린 수용체에 결합하여 위산 분비를 촉진시킴으로써 H2 수용체 길항제의 약제 내성을 유발시킨다(Fig. 1) [2]. 약물 내성의 발생기전은 명확하지 않지만 위 벽세포의 아세틸콜린이나 가스트린 수용체 수의 증가(up-regulation), 히스타민 H2 수용체의 감작(sensitization), 위산 분비의 억제성 신경호르몬 조절 기능의 저하(impairment of inhibitory neurohormonal control of acid secretion), 히스타민 수용체의 만성적인 경쟁적 억제 후 일어나는 수용체 회전율(receptor turnover)의 변화 등이 제시되고 있다[8].

최근 라니티딘의 경우 잠재적으로 세계보건기구가 인정한 발암 추정물질인 N-니트로소디메틸아민(N-nitrosodimethylamine, NDMA)으로 전환될 수 있어 2019년 식품의약품안전처에서 제조, 수입, 및 판매를 중지하였다. 비록 최근 미국 식품의약국 산하 약물평가연구센터(Center for Drug Evaluation and Research)에서 시행한 임상시험에서는 라니티딘이 혈장 또는 소변에서 NDMA뿐 아니라 NDMA의 전구체인 디메틸아민(dimethylamine)도 증가시키지 않았다고 보고하였으나[9], 향후 임상에서 다시 사용될 가능성은 매우 낮을 것으로 생각된다.

2) H2 수용체 길항제의 임상적 이용

H2 수용체 길항제의 위산 분비 억제 효과를 PPI와 비교하면 위산과 관련된 여러 질환(Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, 역류성 식도염, 소화성 궤양 등)의 치료에서 H2 수용체 길항제는 PPI에 비해 덜 효과적이었다[2,10-12]. 따라서 산 관련 질환의 치료에서 H2 수용체 길항제는 일차 약제로 잘 사용되지는 않는다. 하지만 PPI 제제나 P-CAB 제제와는 달리 H2 수용체 길항제는 혈중 가스트린 농도를 덜 상승시키므로 산 분비 억제제의 장기 투여가 필요한 경우 장기 부작용 측면에서 H2 수용체 길항제의 사용이 권고될 수도 있다[13].

예를 들면 스테로이드 소염제 연관 궤양의 치유는 더 강력한 위산 억제 효과가 있는 PPI와 비교하여 H2 수용체 길항제의 효과는 낮은 것으로 보고된다[14]. 다만 고용량 파모티딘 투여의 경우 표준 용량의 파모티딘, 혹은 위약(placebo)보다 비스테로이드성 소염진통제(non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, NSAIDs) 연관 위궤양에서 더 나은 치료 효과를 보여[15], 소화성 궤양의 치료 목적으로 H2 수용체 길항제를 사용하는 경우에는 파모티딘을 고용량으로 사용해 볼 수 있다.

마찬가지로 표준 용량의 H2 수용체 길항제는 NSAIDs 연관 궤양의 예방에는 효과적이지 않았다. 시메티딘 400 mg을 10개월간 취침 전에 복용한 이전 연구를 보면 궤양의 예방에 효과적이지 않았으며[16], 라니티딘의 예방적 복용은 NSAIDs 복용으로 인한 십이지장 궤양의 발생률은 감소시켰으나 위궤양의 발생률은 감소시키지 못했다[17,18].

GERD에서 H2 수용체 길항제는 역류로 인한 증상의 호전과 식도염의 치유에 있어 위약보다 유의한 효과가 있다[19]. 특히 H2 수용체 길항제는 작용 시작 시간이 빠르다는 장점이 있어 증상이 심하지 않은 환자에서 증상 호전을 위해 사용할 수 있다. 하지만 PPI와 H2 수용체 길항제의 증상 개선 효과를 비교하면 PPI는 H2 수용체 길항제에 비해 우월한 효과를 보였다[20]. 미란성 역류 질환(erosive reflux disease)에서 PPI는 H2 수용체 길항제보다 증상 개선 및 점막 치유 효과 측면에서 우월하였다[21]. 메타분석 결과에서 PPI 제제가 H2 수용체 길항제에 비해 역류 증상이 남아있을 위험도(risk ratio, RR)는 0.67 (95% CI, 0.57~0.80)이었다[22]. 비미란성 역류 질환(non-erosive reflux disease)에서도 PPI는 H2 수용체 길항제보다 증상 개선에 효과적이었다(RR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.62~0.97) [23].

H2 수용체 길항제는 야간 위산 분비 억제에 효과적이며, 상대적으로 주간 위산 분비 효과는 제한적이다[24,25]. 따라서 주간에 주로 증상이 발생하는 경도(Los Angeles 분류상 A 또는 B) 역류성 식도염의 치료에는 H2 수용체 길항제의 효과가 낮고 PPI 제제가 더 효과적이다[26]. 하지만 PPI에 반응이 없는 불응성 환자들이 있으며, 특히 야간 산 분비 억제 실패는 PPI의 불응성의 중요한 원인 중 하나이다[27,28]. 이러한 경우 추가로 취침 전 H2 수용체 길항제를 병용 투여하는 것이 효과적일 수 있다[29,30]. H2 수용체 길항제는 야간 히스타민 분비(night time histamine surge)로 인한 기저 위산 분비(basal acid output) 증가를 의미하는 야간 위산 돌파(nocturnal gastric acid breakthrough)를 억제하는 효과가 있기 때문이다[29]. 오메프라졸(omeprazole) 20 mg을 하루 2회 복용하면서 추가로 라니티딘 150 mg 또는 300 mg을 취침 전에 복용하였을 때 야간 위산 분비 억제 실패가 소실되었으며[31], 란소프라졸(lansoprazole)과 파모티딘의 병용 요법도 야간 위산 분비 억제 실패에 효과적이었다고 보고하였다[32].

흥미로운 것은 니자티딘의 경우 다른 H2 수용체 길항제와는 달리 아세틸콜린 분해효소(cholinesterase)를 억제하는 작용이 있어 콜린성 신경의 시냅스에 아세틸콜린의 농도를 높여 위장관의 운동을 활성화시키는 효과가 있다[33]. 이론적으로 위장관 운동의 활성화는 식도 연동 운동을 증가시키고 하부식도조임근(low esophageal sphincter) 압력의 증가, 위 배출(gastric emptying)을 촉진시켜 GERD 증상 호전에 도움이 된다[34]. 또한 니자티딘은 콜린성 신경을 활성화시켜 침 분비를 증가시킨다[35,36]. 침 분비의 증가는 식도로 역류된 위산 청소능을 향상시켜 GERD 치료에 도움이 된다[37].

2. 양성자펌프억제제

1) 작용기전 및 약리학적 특성

PPI는 위 벽세포에서 활성화된 양성자펌프에 비가역적으로 결합하여 효소를 불활성화하여 수소이온의 방출을 차단시켜 위산을 억제하는 약제이다[38]. H2 수용체 차단제가 히스타민 H2 수용체에만 작용하는 것과 달리 PPI는 위산 분비의 최종 단계인 양성자펌프에 직접적으로 작용하기 때문에 더 강력한 위산 분비 억제가 가능하며, 장기간 사용 시 가스트린 증가에도 불구하고 약물 내성이 발생하지 않는다.

PPI는 위산에 취약하므로 장용정으로 투여되어야 한다. 또한 흡수된 PPI는 간에서 대사되어 배설되는데, 이 과정은 cytochrome P450의 CYP2C19와 CYP3A4에 의해 이루어지며, 각 효소에 대한 의존도는 약제마다 다소 차이를 보인다. 예를 들면 CYP2C19의 대사 의존도가 가장 높은 오메프라졸은 동일 효소계를 통하여 대사되는 다른 약제의 약리 작용에도 영향을 주기 때문에 와파린(warfarin)이나 클로피도그렐(clopidogrel) 등의 심혈관계 약물을 복용하는 환자에서는 주의가 필요하다. 비록 클로피도그렐을 사용하는 환자에서 PPI를 병용하였을 때 심혈관계 사망률이 증가한다는 근거는 미약하지만, 클로피도그렐 활성도를 떨어뜨리는 강도는 오메프라졸, 에소메프라졸(esomeprazole), 란소프라졸, 판토프라졸(pantoprazole), 라베프라졸(rabeprazole), 일라프라졸(Ilaprazole) 순이므로 클로피도그렐을 사용하는 환자에서 PPI를 사용할 경우 일라프라졸, 라베프라졸, 판토프라졸과 같은 PPI를 선택하거나 두 약제를 12시간 간격으로 복용하는 것이 안전하다[39,40].

또한 CYP2C19 유전자의 4번과 5번 axon은 유전자 다형성이 존재한다. Axon의 변이가 없는 것은 homogenous extensive metabolizer (EM), 4번 또는 5번 중 한 곳에 변이가 생긴 것은 heterogenous EM, 둘 다 변이가 생긴 것은 poor metabolizer (PM)로 구분한다[41]. 따라서 wild/wild type인 homogenous EM 유전형인 경우 흡수된 약제가 간에서 대부분 대사되어 충분한 약효가 나타나지 않을 수 있기 때문에 오메프라졸, 란소프라졸, 판토프라졸의 효과가 떨어질 수 있으므로 CYP2C19가 아닌 다른 경로(non-enzymatic pathway)로 대사되는 라베프라졸이나 일라프라졸 등으로 바꾸어 볼 수 있다[42].

혈액을 통해 벽세포의 분비소관에 축적된 PPI는 벽세포에서 산이 분비되어 pH가 4 미만이 되면 PPI의 비활성화된 benzimidazole이 양이온인 sulfonamide로 바뀌어(protonation) 양성자펌프의 cystein에 결합함으로써 위산 분비를 차단하게 된다[18]. 따라서 약리학적으로는 식전, 그것도 하루의 첫 식사 시간(아침) 전 30분~1시간 전에 투여하는 것이 가장 효과적이다[43]. PPI는 자극으로 활성화된 양성자펌프만 선택적으로 차단한다. 따라서 산 억제 효과를 나타내기까지 최대 3~5일이 소요되므로 증상 완화를 시킬 정도의 산 억제에 도달하기 위해서는 여러 번 투여가 필요할 수 있다[44]. 한편 약물 투여를 중단하면 양성자펌프는 3~7일에 걸쳐 서서히 재생된다.

덱스란소프라졸(dexlansoprazole)은 란소프라졸의 R 이성질체로 지연 방출 캡슐(Dexilant®)로 개발되어 사용하고 있다. 이는 두 가지의 장용코팅 과립이 근위부 소장과 원위부 소장에서 두 번 용출되어 두 번의 혈중농도 최고점을 보임으로써 야간까지 효과를 지속할 수 있고 식사 전과 후의 복용 시간에 큰 차이를 보이지 않아 유용하게 사용할 수 있다[45]. 또한 PPI의 위산에 취약한 단점을 보완하여 안전성을 유지하여 최대 효과를 보면서도 위의 산도를 빨리 높일 수 있도록 오메프라졸이나 에소메프라졸에 중탄산염나트륨(sodium bicarbonate) 등을 섞어 즉시 용출되도록 한 제형이 개발되어 사용되고 있으며 빠른 위산 분비 억제 효과로 치료에 도움을 주고 있다.

2) 양성자펌프억제제의 임상적 이용

PPI는 다양한 위산 관련 질환의 치료와 예방에 사용되고 있다. 통상적으로 합병증을 동반하지 않는 소화성 궤양의 경우 십이지장 궤양은 4주, 위궤양의 경우 6~8주간 표준 용량(오메프라졸 20 mg, 란소프라졸 30 mg, 라베프라졸 20 mg, 판토프라졸 40 mg)의 PPI를 투여한다. 또한 PPI는 비정맥류 상부위장관 출혈(non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding)의 치료의 1차 약제이다[46]. 활동성 출혈이나 급성기에는 내시경 전에 고용량 PPI 치료(초회 pantoprazole 80 mg 정주 후 72시간 동안 8 mg/h 지속 주입)를 시행하는 것이 재출혈 예방, 수술적 치료 및 사망 위험률 감소에 효과적일 수 있다고 보고되었으며[47,48], 최근 연구에서는 초회 80 mg 정주 후 12시간마다 40 mg을 투여하는 것도 지속 주입과 비슷한 재출혈 예방 효과를 보여주었다[49].

또한 약제 연관 소화성 궤양(drug-induced peptic ulcer)의 예방 및 치료에서도 PPI는 핵심적인 약제이다. 최근 국내 임상지침 개정안을 보면, 이전과 마찬가지로 NSAID 관련 소화성 궤양 및 합병증의 예방을 위해 PPI 저용량 투약을 권고하며, 저용량 아스피린을 장기 복용하는 환자에서 소화성 궤양 출혈의 과거력이 있는 경우 궤양 및 출혈을 예방하기 위해 PPI 투약을 권고한다[50]. 또한 항응고제를 복용하는 환자에서 소화성 궤양 출혈의 고위험군은 상부위장관 출혈을 예방하기 위해 양성자펌프억제제 투약을 권고하고 있다[50]. 헬리코박터 균은 위내 산도에 민감하며 PPI 제제의 anti-Helicobacter effect가 정립되어 있어, 제균 치료에서 PPI는 필수 약제이다[51].

여러 위산 관련 질환 중에서도 PPI는 GERD 환자의 초치료 및 유지 치료를 위해 가장 많이 사용되고 있다. 역류성 식도염의 치료에 있어서 PPI의 종류에 따른 효능을 보면 표준 용량의 PPI를 투여하였을 때 약제 종류와 상관없이 약 90%의 치료율을 보여주었다[52-55]. PPI는 GERD의 유지 치료(maintenance therapy)에도 사용되며, 저용량의 PPI를 지속적으로 사용하는 지속 복용법(continuous therapy)과 증상이 발생하였을 때만 투여하는 필요 시 요법(on-demand therapy)의 두 가지 전략이 있다. 최근 메타분석 결과를 보면 심한(Los Angeles 분류상 C 또는 D) 미란성 식도 질환을 제외하면 경도의 역류성 식도염이나 비미란성 역류 질환에서 지속 복용법과 필요 시 요법 사이에 증상 조절에 유의한 차이는 없다고 보고되었다[20].

3) 양성자펌프억제제 장기 부작용

전술한 바와 같이 PPI의 장기 사용에 대해서는 이전부터 부작용에 대한 우려가 있어 왔으며, 이는 PPI 사용과 연관된 저산증(hypochlorhydria) 및 고가스트린혈증(hypergastrinemia) 등과 연관되어 있다. 이론적으로는 고가스트린혈증은 위암 발생 위험을 증가시킬 수 있으나 실제 임상에서 위암 발생을 증가시키는지에 대해서는 논란이 있다[56-58]. 적어도 PPI 장기 사용자의 위 점막에서 위선 내강(gastric gland lumen)으로의 벽세포 돌출, 위저선의 낭성 확장, 선와상피 과형성(foveolar epithelial hyperplasia)이 초래되며, 내시경에서 보이는 위저선 용종(fundic gland polyps), 과형성 용종(hyperplastic polyps), multiple white and flat elevated lesions, 조약돌 모양의 점막(cobblestone-like mucosa), 흑색 반점(black spots) 등이 PPI 사용과 연관되어 있다고 보고되고 있다[59]. 이러한 조직학적 변화는 PPI 중단 후 호전될 수 있어 가역적이라고 알려져 있으나[59], 헬리코박터 제균 치료를 시행하더라도 PPI 제제의 장기 사용으로 인한 위암 발생 위험이 증가할 수 있다는 연구도 있어 주의가 필요하다[60].

PPI 사용은 폐렴, 골절, Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) 관련 설사, 마그네슘 결핍, 장염, 심혈관 질환, 만성 신부전, 치매 그리고 전체 사망률과 연관이 있다고 알려져 있다[61,62]. 하지만 PPI와 각 질병과의 연관성에 대한 연구는 일치된 결과를 보여주고 있지 못하다[62]. 최근 발표된 다국적 대규모 임상 시험에 따르면, 항혈전제(aspirin 혹은 rivaroxaban)을 복용하는 환자에서 PPI 장기 복용군과 대조군 간 심근경색, 뇌경색, 또는 심혈관 질환에 의한 사망 위험도에는 차이가 없었으나, 대조군에 비해 PPI 복용군에서 감염성 장염 발생 위험도가 증가하였다(RR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.01~1.75) [63]. 또한 이 연구에서 위축성 위염, 폐렴, 골절, C. difficile 연관 설사, 만성 폐쇄성 폐질환, 당뇨, 만성 신부전, 치매 발생의 각각에 대한 위험도 차이는 없었다.

최근 PPI 장기 투여가 coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) 감염의 중증도를 증가시킬 수 있다는 연구 결과들이 보고되고 있다. 최근 국민건강보험심사평가원 자료를 분석한 연구에서도 PPI 투여는 COVID-19 감염률을 증가시키지는 않지만, 감염자의 중증도를 증가시킬 수 있다고 보고하였다[64]. 반면 SARS-CoV-2 검사를 시행받은 97,674명의 미국 재향 군인을 대상으로 PPI의 사용에 따른 COVID-19 감염의 중증도를 분석하였을 때 성향점수가중분석(propensity score-weighted analysis)을 하지 않았을 때에는 PPI 사용이 중증도 위험을 유의하게 증가시킨 반면(OR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.13~1.43), 성향점수가중분석을 하면 통계적으로 유의하지 않음(OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.91~1.16)을 보고하였으며, 앞서 언급한 국민건강보험심사평가원 연구를 포함한 이전 연구는 중증 CODIV-19 감염증의 조작적 정의 문제나 불충분한 공변량(covariates) 보정 등의 비뚤림(confounding)이 있을 수 있다고 지적하였다[65]. 최근의 메타분석에 따르면 60세 미만, 입원 중 PPI의 사용, 동양인에서 PPI의 사용은 COVID-19 감염증의 중증도와 연관되어 있었다[66]. 하지만 포함된 연구들이 이질적이며, PPI를 투여하는 환자의 임상적 특성(비만, 기저 질환 등)에 의한 역인과관계(protopathic bias)의 가능성도 있어 메타분석 결과를 그대로 받아들이는 것은 주의가 필요하다[67].

따라서 현재까지의 근거로는 PPI 장기 사용이 건강 및 질환에 미치는 영향은 크지 않을 것으로 생각된다. 하지만 일부 PPI 장기 부작용에 대한 후속 연구 결과를 추시할 필요가 있다.

3. 칼륨경쟁적 산 억제제

1) 작용기전 및 약리학적 특성

P-CAB는 H+, K+-ATPase의 K+ exchange channel에 경쟁적으로 결합하여 H+ 교환과정을 방해함으로써 위산 분비를 억제하는 약제이다[68,69]. 양성자펌프 결합이 가역적이고 경쟁적이며 위산 분비 억제 효과가 빠르고 길게 나타낸다[69]. 또한 PP와 달리 P-CAB는 식사를 통한 양성자펌프 활성화가 필요하지 않으므로 식전, 식후 복용에 관계없이 효과적이며, P-CAB는 활성화되지 않은 양성자펌프까지 억제하기 때문에 PPI와는 달리 최대 산 억제 효과에 하루 만에 도달할 수 있다[70].

과거 1세대 P-CAB 제제로 레바프라잔(revaprazan)이 처음 출시되어 소화성 궤양 등의 치료에 사용되었으나, 효과가 오메프라졸보다 우월하지 않았으며, 간수치 상승 등의 부작용으로 현재 임상에서 널리 이용되지 않고 있다[70,71]. 한편 pyrrole derivative인 보노프라잔(vonoprazan)이 일본에서 개발되어 2015년 이후 임상에 이용되고 있다. 보노프라잔은 전술한 P-CAB 제제의 장점뿐 아니라, 위산에도 안정적이며 수용성이고[68], 기존의 약제보다 위산 분비 억제 효과가 더 높으며[72,73], PPI의 경우 pH가 4 미만이 되어야 protonation에 의해 활성화되는 전구약물(prodrug)인 것과 대조적으로 P-CAB 제제는 그 자체가 활성형이어서 protonation이 필요하지 않으므로 pH에 상관없이 양성자펌프의 억제 작용을 나타내고, CYP2C19의 유전자형에 영향을 받지 않으므로 약제 상호 작용이 적다는 장점을 가지고 있다[74]. 특히 보노프라잔은 양성자펌프에 결합한 후 천천히 분리되면서 위 점막에 24시간 이상 머물러 있기 때문에 지속적인 산억제가 가능하다[70,75].

이전 연구 및 메타분석에서 보노프라잔의 단기 투여는 비교적 안전하다고 보고되었으나, 강력한 위산 억제로 인해 발생되는 고가스트린혈증은 잠재적인 문제가 될 수 있다[76,77]. 비록 약제를 중단하면 혈중 가스트린 농도는 빠르게 정상화되며[78], 비록 고가스트린혈증이 향후 위암 발생 위험을 증가시킨다는 직접적인 증거는 없으나 향후 장기간 추시가 필요하다[70].

한편 최근 국내에서도 P-CAB 신약으로 benzimidazole 유도체인 테고프라잔(tegoprazan)이 출시되었다[79]. 테고프라잔 또한 가역적, 농도 의존적으로 결합하여 위산 분비를 저해하며 위산에 의한 활성화 단계를 거치지 않고도 직접 양성자펌프를 억제한다. 테고프라잔도 여러 임상 연구에서 소화성 궤양 및 위식도 역류 질환의 치료에서 PPI와 유사한 효과를 보여주었다. 또한 펙수프라잔(fexuprazan, DWP14012) 또한 빠르고 강력한 위산 분비 억제 효과를 보였고, 최근 3상 연구에서 미란성 식도염 환자에서 내시경상 점막 결손 치료로 평가한 치유율이 펙수프라잔 40 mg이 에소메프라졸 40 mg과 비교하여 비열등성을 보여주어 2022년 중 해당 질환에 대한 적응증을 가지고 국내 출시될 예정이다(Table 1) [80,81].

2) 칼륨경쟁적 산 억제제의 임상적 이용

P-CAB 역시 다양한 산 관련 질환의 치료에서 PPI의 역할을 대체할 수 있을 것으로 기대된다[75]. 보노프라잔 및 테고프라잔은 소화성 궤양의 치료에서 PPI 제제와 비열등성을 보여주었다[82]. 또한 P-CAB의 빠른 산 억제 효과는 이론적으로 헬리코박터 제균 치료에서 PPI보다 더 효과적일 가능성을 시사한다[83]. 보노프라잔은 저용량 아스피린이나 NSAID를 복용하는 환자에서 약제 연관 궤양 예방 효과를 보여주었다[84,85]. 일본에서 보노프라잔은 기존의 PPI기반 3제요법(PPI+amoxicillin+clarithromycin)보다 더 높은 제균 성공률을 보여주어 일본에서는 보노프라잔이 헬리코박터 제균 치료의 표준 3제요법으로 승인받았다[86,87].

GERD에서 P-CAB 제제의 최근 임상 시험 결과를 보면 일본 및 여러 아시아 국가에서 시행된 3상 임상 시험 결과를 보면 보노프라잔은 소화성 궤양 및 역류성 식도염의 치료에 매우 효과적이었다[88-90]. 동양인 역류성 식도염 환자를 대상으로 시행된 연구에서 란소프라졸과 비교하여 보노프라잔의 안정성 및 비열등성을 평가한 연구에서, 일차 평가 변수인 8주째 역류성 식도염의 치유율은 보노프라잔 투여군 92.4%, 란소프라졸 투여군 91.3%로 보노프라잔의 비열등성이 입증되었으며[91], 이는 일본에서 시행된 이전 3상 연구 결과와 일치한다(99.0% vs. 95.5%) [92]. 하지만 보노프라잔은 비미란성 역류 질환에서 가슴쓰림 증상을 호전시키는 데에는 우월한 효과를 입증하지 못하였다[93]. 비미란성 역류 질환 임상 시험의 경우 일차 목적(primary endpoint)인 증상 평가에서 위약 효과(placebo effect)가 크므로 유의성을 입증하기 어려운 제한점이 있다. 그럼에도 불구하고 장기 추적 관찰 연구에서 보노프라잔(하루 10 mg 투여)은 1개월 후 89%의 환자에서 역류 증상을 호전시켰고, 이러한 효과는 81.6%의 환자에서 1년간 유지되었다고 보고하였다[94]. 한편 테고프라잔은 최근 진행된 다기관 임상 시험에서 미란성 식도염뿐 아니라 비미란성 위식도 역류 질환 치료에 위약 대비 높은 효능을 보여주었다(complete resolution of major symptoms at week 4: 42.5%, 48.5%, 24.2% in tegoprazan 50 mg, tegoprazan 100 mg, and placebo groups, respectively) [95,96].

이러한 임상 결과로부터 최근 국내 가이드라인에서도 P-CAB 제제가 위식도 역류 질환의 치료에 일차 약제로 사용될 수 있음을 명시하였다[20]. 보노프라잔과 테고브라잔에 대해서 진행된 총 4편의 무작위 임상 시험에 대한 메타분석 결과를 보면 P-CAB 제제는 PPI보다 열등하지 않았으며, 부작용 측면에서도 차이가 없었다[20]. 특히 Los Angeles 분류 C, D에 해당되는 심한 미란성 식도염을 보이는 위식도 역류 질환 환자에서는 PPI보다 P-CAB 제제가 더 효과적일 수도 있으나[97], 아직 근거는 부족하며 추가 연구가 필요하다.

3) 칼륨경쟁적 산 억제제 장기 부작용

P-CAB 제제는 최근에 임상에서 널리 이용되고 있어, PPI 제제에 비해서는 장기 투여로 인한 부작용에 대한 연구는 많지 않다. 하지만 P-CAB 제제도 강력한 위산 분비 억제제이며, 특히 일부 연구에서는 보노프라잔의 경우 PPI보다 더 심한 고가스트린혈증을 일으키기 때문에 위식도 역류 질환 환자에서 P-CAB 제제가 장기간 투여되는 경우 이로 인한 위선암(gastric adenocarcinoma) 및 장크롬친화 세포 과형성(enterochromaffin-like cell hyperplasia)과 연관된 위 신경내분비종양(neuroendocrine tumor) 발생 등 부작용에 대한 우려가 있다[98].

최근 보노프라잔을 유지 요법으로 투여한 역류성 식도염 환자에서 선와형 위선암(foveolar-type gastric adenocarcinoma)이 발생하였다는 증례 보고가 있다[99]. 이러한 우려에 대해서 표준 용량의 보노프라잔 투여에도 위식도 역류 질환 증상 조절이 되지 않는 경우 보노프라잔 용량을 증량하기보다는 라퓨티딘과 같은 H2 수용체 길항제를 추가하는 것이 효과적으로 증상을 조절하면서 혈중 가스트린 농도 상승을 최소화할 수 있는 방법일 수 있으며[100], 무스카린 M1 수용체 길항제인 pirenzepine을 보노프라잔과 병용하는 것이 혈중 가스트린 농도를 낮출 수 있었다고 보고하고 있다[101].

하지만 보노프라잔 투여 후 발생하는 심한 고가스트린혈증은 일본인 대상 연구에서 주로 보고된 반면 서양인에서는 보노프라잔 투여 시 PPI 투여로 인한 고가스트린혈증과 비슷한 수준으로 상승하였다고 보고되었다[72,73]. 또한 테고프라잔의 경우 보노프라잔에 비해 혈중 가스트린 농도가 덜 상승하였다고 보고하고 있다[102]. 전술한 바와 같이 PPI 장기 투여로 인한 고가스트린혈증이 위암 발생에 미치는 영향에 대한 연구 결과들은 서로 일치하지 않아서, PPI 투여가 위암 발생 위험을 증가시키거나[103], 위암이나 신경내분비종양 발생에 영향을 미치지 않는다는[104] 메타분석 결과들이 혼재하고 있으며, 오히려 PPI가 가스트린의 증식 및 항세포자멸사 효과(anti-apoptotic effects)를 억제하는 기전으로 가스트린 연관 암화(gastrin-associated carcinogenesis) 과정을 억제할 수 있다는 연구도 있다[105]. 따라서 P-CAB 제제가 실제로 PPI보다 더 혈중 가스트린 농도를 상승시키는지 추가 연구를 통한 확인이 필요하며, 실제로 혈중 가스트린 농도를 더 상승시킨다고 하더라도 위암 발생 위험 증가를 일으키는지에 대한 장기 투여 안전성 연구가 필요하다. 다만 잠재적 위험성이 있고 위암 발생 외에도 위산 억제로 인한 다른 부작용도 알려지고 있으므로 P-CAB 제제는 꼭 필요한 환자에게 최소 기간 동안 사용하는 것이 추천된다.

결 론

지금까지 여러 산 분비 억제제의 작용 기전, 종류, 임상에 대해서 살펴보았다. 환자에게 적절한 약물을 처방하기 위해서는 각 약제의 특성, 장점 및 부작용에 대한 충분한 이해가 필요하다. 다양한 산 분비 억제제의 특성 및 국내 급여 적응증에 대해서는 Table 1에 따로 정리하였다. 이들 약제는 임상에서 다양한 적응증의 산 관련 질환(acid-related disease)의 치료에 사용되고 있으며, 약제의 장기 사용으로 인한 부작용에 대해서는 향후 연구 결과에 대한 추시가 필요하다.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.