헬리코박터 파일로리 감염에 대한 맞춤형 치료의 최근 경향

Recent Trends in Tailored Treatments for Helicobacter pylori Infection

Article information

Trans Abstract

The efficacy of the standard triple eradication regimen for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is gradually decreasing due to increased antibiotic resistance of H. pylori, which is represented by clarithromycin resistance. This is an important issue for clinicians. Tailored therapies for H. pylori infection, including culture-based susceptibility testing and molecular methods detecting genetic mutations that increase resistance to antibiotics, have been introduced to overcome the high treatment failure rate of the standard triple regimen. The treatment results have been satisfactory. In addition to the H. pylori-related factors, the CYP2C19 gene polymorphism, in terms of host factors, affects the effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors. This article reviews the status of the tailored therapies for H. pylori infection along with the proven therapeutic effects and benefits of such treatments in Korea, where the resistance to antibiotics such as clarithromycin, metronidazole, and quinolone is prevalent.

서 론

헬리코박터 파일로리(Helicobacter pylori, H. pylori)는 그람 음성 나선형 세균으로 만성위염, 소화성 궤양, 점막관련림프조직 림프종, 위암 발생의 원인이며, 전 세계 인구의 절반이 감염되어 단일 감염질환으로 가장 높은 빈도를 보인다[1,2]. 국내 유병률은 2015~2016년 대한상부위장관‧헬리코박터학회의 전국 조사 결과 51.0%로 지역 간에 유병률의 차이가 있고 과거에 비해서 감소하는 추세이지만 여전히 국내에서 중요한 문제이다[3].

국내에서는 일차 제균 치료로 양성자펌프억제제(proton pump inhibitor, PPI) 표준용량, amoxicillin 1 g, clarithromycin 500 mg을 하루 2회 7일에서 14일 투여하는 것을 표준 3제요법으로 권고하며, clarithromycin 내성이 의심되는 경우 PPI 표준용량 하루 2회, metronidazole 500 mg 하루 3회, bismuth 120 mg 하루 4회, tetracycline 500 mg 하루 4회의 4제요법을 7일에서 14일 투여하도록 권고하고 있다[4]. 하지만 국내에서 전국적인 다기관 연구로 시행된 연구에서 일차 제균 치료에 따른 제균 성공률은 2008~2010년 80.0~81.4%로 감소하는 추세로 확인되었다[5]. 또한, 메타분석에서도 2001년 치료 의향 분석(intention to treat analysis, ITT) 82.4%, 계획서 순응 분석(per protocol analysis, PP) 82.5%였던 제균 성공률이 2013년 ITT 66.4%, PP 76.4%로 감소함이 확인되었다[6]. 이는 국제적으로 이상적인 제균 치료율을 ITT 80%, PP 90%로 제시한 것에 비하여 못 미치는 결과이다[7].

제균 실패의 주 원인은 환자의 나이, 흡연 여부, 항생제 내성과 복약 순응도 저하이고, 특히 clarithromycin에 대한 내성 증가가 주된 치료 실패의 주요한 원인으로 알려져 있다[8-10]. 더구나 항생제 내성은 국가 간 차이는 물론 국내에서도 지역에 따른 차이가 확인되었고, 두 개 이상의 항생제에 내성을 보이는 다제내성(multiple drug resistance, MDR)도 전국적으로 25.2% (서울특별시 13%, 전라도 31%)로 높은 MDR 비율과 지역 간 차이가 보고되었다[11]. 제균 성공률의 향상을 위해 여러 방법이 시도되고 있으나, 대만의 항생제 제한 정책 이후 clarithromycin과 metronidazole의 낮은 항생제 내성률이 보고된 결과[12]에서 알아볼 수 있듯이 제한적이면서 적절한 항생제의 사용이 가장 이상적인 치료 방법이라고 생각된다.

맞춤형 치료(tailored therapy)는 치료 전에 개별적인 약물반응을 예측해서 치료하는 개념이다. 항생제 내성 검사를 바탕으로 개별적인 치료를 통해 전체적인 치료의 효율을 높일 수 있고, 항생제 오남용을 막을 수 있는 장점이 있다. 특히 항생제 내성률이 높고 지역 간 차이가 큰 현재 상황에서 맞춤형 치료는 더욱 효과적일 것으로 기대된다. 본고에서는 맞춤형 치료의 최근 연구 경향을 알아보고자 한다.

본 론

1. 세균배양을 통한 H. pylori 항생제 감수성 검사

세균배양을 통한 접근은 H. pylori ‘세균’이라는 측면에서 기본적이고 궁극적인 진단 및 치료법이다[13,14]. 그러나 H. pylori는 미세호기성 세균의 특성상 배양 조건이 까다롭다. 분변을 이용하는 방법[15]도 있으나 기본적으로 내시경 검사를 통한 조직검사로 얻어진 검체가 가장 좋다는 점에서 침습적인 검사 방법이다[16]. 또한 배양까지 10~14일 정도의 시간이 걸리며 항생제 감수성 검사 비용이 추가되는 등 많은 노력과 비용이 소요된다는 점에서 일상적인 진료 환경에서의 적용이 쉽지 않다[17]. 그럼에도 불구하고 항생제 감수성 검사를 바탕으로 한 치료는 획일적인 일차 치료제를 사용하였을 때보다 제균 성공률이 높고, 검사 비용이 추가되었지만 제균 치료가 모두 완료되었을 때는 오히려 비용 효과적이었다는 보고가 있다[18,19]. 또한, 한 환자에서 분리된 H. pylori에서 서로 다른 감수성을 가지는 균주가 혼재된 결과를 보이는 경우가 있고, 이 원인으로는 서로 다른 계통(strain)의 H. pylori가 혼합 감염되어 각각 다른 감수성을 보이거나 한 계통 내에서 감수성 균주와 내성을 획득한 균주가 함께 존재하고 있을 가능성을 생각해 볼 수 있다[20-24]. 그러므로 정확한 내성 연구를 위해서는 세균배양을 통해 많은 수의 균주를 확보하여 검사를 하는 것이 바람직하다고 볼 수 있다.

2. 항생제 내성 유전자 검사를 통한 H. pylori의 항생제 감수성 검사

세균배양의 어려움과 오랜 검사시간의 단점을 개선하기 위해 항생제 내성 유전자를 이용한 분자진단 검사에 대한 연구가 지속적으로 이루어졌고, 우리나라를 포함하여 세계 각국에서 이를 이용한 검사법이 개발되어 상업적으로 이용되고 있다. 내시경 검사를 통한 조직 검체를 통해 검사가 이루어지며, dual priming oligonucleotide (DPO)-PCR, PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism, fluorescence in situ hybridization, real-time PCR, multiple genetic analysis system 등 다양한 검사 방법이 개발되었다[25]. H. pylori 유전자의 점 돌연변이가 항생제 내성과 관련이 있는데, clarithromycin의 경우 23S rRNA 유전자의 A2142G, A2143G 변이가 관련되고, fluoroquinolone의 경우 gyrA 유전자의 변이, tetracycline의 경우에는 16S rRNA가 관련된다[16]. Amoxicillin과 metronidazole도 각각 plp1, rdxA&frxA 유전자가 관련되어 이를 검사하면 해당 항생제에 대한 내성 상황을 알아볼 수 있다. 하지만 amoxicillin이나 metronidazole은 유전자 변이의 다양성으로 인해 검사 도구의 개발이 어렵고, tetracycline의 경우는 내성률이 낮은 편이어서 개발의 효용성이 낮은 편이다. 최근 소개된 DPO-PCR (Seegene Institute of Life Science, Seoul, Korea) 방법은 H. pylori 감염의 진단뿐 아니라 clarithromycin 내성도 함께 파악할 수 있게 고안되어 빠르게 환자의 일차 약제를 선택하는 데 도움이 된다[26,27].

3. 항생제 감수성에 따른 맞춤 치료 현황

1) 세균배양을 통한 맞춤 치료 현황

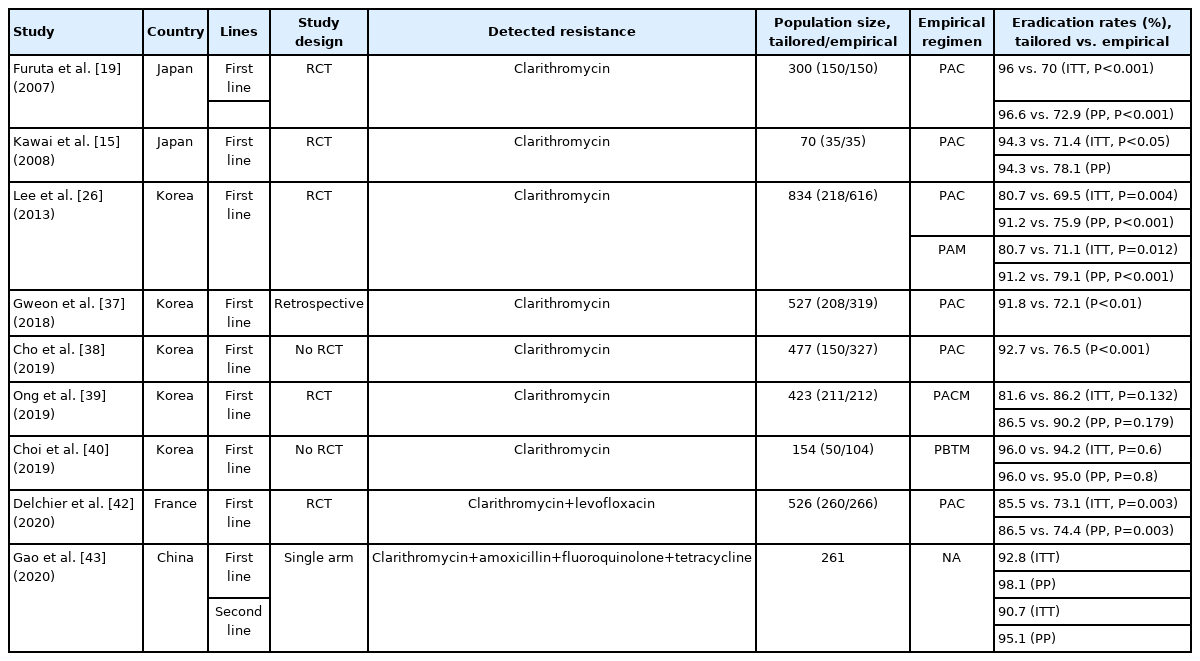

우리나라를 포함하여 여러 나라에서 세균배양을 통한 항생제 감수성 검사 후 H. pylori 치료 성적이 보고되어 있다(Table 1). 주로 1차 치료에서 표준 3제요법과의 비교가 많았고, 무작위 배정 연구도 다수 포함되어 있다. 2016년 Chen 등[13]이 2015년까지 발표된 연구를 바탕으로 보고한 메타분석에 따르면, 일차 치료에서 맞춤형 치료가 경험적 치료에 비해 높은 제균율(pooled RR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.96~1.39)을 보였다. 일차 치료 방법으로 clarithromycin 기반의 3제요법을 사용한 우리나라의 연구 결과를 살펴보면 2014년 Park 등[28]이 경험적 치료에 비한 맞춤형 치료의 우수성(94.7% vs. 71.9%, ITT; P=0.002)을 보고하였고, 최근 Lee 등[29]의 보고에서도 일관적으로 맞춤형 치료는 우수한 제균 성공률(93.1%, ITT)을 보고하고 있다. 동일한 방법의 경험적 치료를 시행한 이탈리아의 연구에서도 일관적으로 맞춤형 치료가 경험적 치료에 비해 치료의 우위를 보였다[18,30,31]. 또한 일차 치료 방법으로 bismuth 기반의 4제요법을 사용하는 중국에서 역시 맞춤형 치료의 우위가 확인되었다[32,33]. 하지만 1차 제균 치료 이후 2차 rescue 치료에서는 맞춤형 치료의 효과에 논란이 있다. 2003년 일본에서 Miwa 등[34]은 제균 치료 실패 후 맞춤형 치료를 받은 집단과 일괄적으로 PPI, amoxicillin 그리고 metronidazole을 투여받은 집단을 비교하였을 때, 제균 성공률이 각각 81.6%와 92.4%였으나 통계적으로 차이가 없어 2차 제균 치료 때는 맞춤형 치료가 필요하지 않을 수 있다고 보고하였다. 또한 2018년 대만에서 Liou 등[35]의 보고에서도 제균 치료 실패 후 맞춤형 치료 성공률 78%, 경험적 치료 성공률 72.2% (ITT, P=0.170)로 차이가 없었다. 국내의 연구 결과에서도 2016년 Kwon 등[36]의 발표에 따르면 맞춤형 치료를 시행한 집단이 경험적으로 PPI, moxifloxacin 그리고 amoxicillin을 사용한 집단(87.8% vs. 70.8%, ITT; P=0.026)에 비해 H. pylori 제균 성공률이 높았으나 2차 치료로 권고되는 4제요법인 PPI, bismuth, metronidazole 그리고 tetracycline을 사용하였을 때(87.8% vs. 75.3%, ITT; P=0.077) 통계적으로 유의한 차이를 보이지 않았다. 위의 연구 결과를 종합해 보았을 때 세균배양을 통한 맞춤형 치료는 일차 치료에서 좀 더 유용할 것으로 생각된다.

2) 분자진단법을 이용한 맞춤 치료 현황

항생제 내성 유전자를 이용한 분자진단법에 관한 연구는 주로 일본과 한국에서 이루어졌고, 대부분 1차 제균 치료 때 23S rRNA의 돌연변이를 확인하여 clarithromycin 내성에 따른 맞춤형 치료의 효과를 보고하였다(Table 2). 2007년 일본에서 Furuta 등[19]이 표준 3제요법에 비하여 맞춤형 치료 때 우수한 제균 성공률을 보였고(96% vs. 70%, ITT; P<0.001), 2008년 일본에서 Kawai 등[15]도 표준 3제요법에 비하여 우수한 맞춤형 치료의 제균 성공률(94.3% vs. 71.4%, ITT; P<0.05)을 보였다. 이후 국내 연구 결과도 일관성 있게 맞춤형 치료는 clarithromycin 기반의 표준 3제요법에 비하여 높은 제균 성공률을 보고하였다[26,37,38]. 하지만 clarithromycin 내성에 따른 맞춤형 치료는 PPI, amoxicillin, clarithromycin 그리고 metronidazole을 이용한 동시 치료(concomitant therapy)와 비교하였을 때는 차이가 없었고(81.6% vs. 86.2%, ITT; P=0.132) [39], bismuth 기반의 4제요법을 일차 치료로 사용하였을 때와 비교하여도 제균 성공률의 차이를 보이지 못하였다(96.0% vs. 94.2%, ITT; P=0.6) [40]. 이는 분자진단법 검사의 특성에 기인하는 것이 아니라 앞서 배양 결과를 기반으로 한 맞춤 치료의 경우와 마찬가지로, clarithromycin 내성으로 인한 경험적 치료법들의 제균 성공률 차이와 관계된 것으로 생각된다.

Clarithromycin 내성만 평가가 가능한 분자진단 기법의 한계를 보완하기 위해 국내에서 Kwon 등[41]은 clarithromycin 내성 검사와 metronidazole 사용력을 조사하여 제균 치료를 시행하는 전략을 제시하였고, clarithromycin 내성이 없는 집단, clarithromycin 내성 집단, metronidazole 내성이 의심되는 집단에서 각각 94.4%, 77.8%, 100.0%의 제균 성공률을 보고하였다. 최근 프랑스에서는 clarithromycin과 fluoroquinolone 두 가지 내성 유전자를 동시에 검사할 수 있는 HelicoDRⓇ (Hain Life Science, Nehren, Germany) 검사법을 이용한 1차 치료 다기관 무작위 대조군 연구가 발표되었다[42]. 경험적 치료군은 clarithromycin 기반의 3제요법이었는데, 맞춤형 치료가 높은 제균율을 보여주었다(85.5% vs. 73.1%, ITT; P=0.003). 이 연구에서는 clarithromycin 내성률이 23.3%, levofloxacin 내성률이 12.8%였다. 우리나라의 levofloxacin 내성률은 40%에 육박하여 향후 우리나라에서 HelicoDRⓇ 검사법이 quinolone 포함 제균 치료에 활용될 수 있을 것으로 기대된다[11]. 2020년 중국에서 Gao 등[43]은 real time PCR 기법을 이용하여 clarithromycin 내성을 확인하고, conventional PCR 기법을 이용하여 amoxicillin, fluoroquinolone 그리고 tetracycline의 내성까지 확인한 이후 맞춤형 치료를 시행하였고, 일차 치료에서의 효과뿐 아니라 일차 치료에 실패한 사람들에서의 효과까지 분석을 하였다. 경험적인 치료와 비교를 한 결과는 아니었으나 일차 치료에서 ITT 92.8%, 이차 치료에서 ITT 90.7%의 제균 성공률을 보여 일차 치료뿐 아니라 이차 치료에서도 맞춤형 치료가 효과적일 수 있을 가능성을 보여주었다. 위의 내용을 종합하여 보았을 때, clarithromycin 내성 검사를 이용한 맞춤형 치료는 표준 3제요법에 비하여 우수하지만, 아직 clarithromycin 이외 항생제 내성에 대한 분자진단 도구의 개발이 미흡한 상황이어서, 추가적인 분자진단 도구의 개발과 맞춤형 치료에 대한 연구가 필요한 상황이다.

4. CYP2C19 유전자 다형성(polymorphism)에 따른 맞춤 치료

H. pylori 균주의 항생제 내성에 대한 고려 이외에 적절한 위산 억제 역시 PPI를 기본으로 하는 제균요법의 성공 여부를 결정하는 중요한 요소가 될 수 있다. PPI는 cytochrome P450 (CYP) system 중 주로 CYP2C19 효소에 의하여 대사된다. CYP2C19은 유전자형에 따라 신속대사자(extensive metabolizer), 중간대사자(intermediate metabolizer), 대사저하자(poor metabolizer)로 분류되며 신속대사자의 경우 대사저하자에 비하여 PPI 대사가 빨라 생체 이용률이 떨어진다[44]. CYP2C19 유전자형에 따른 맞춤 치료의 전략은 CYP2C19의 영향을 덜 받는 PPI를 사용하거나, CYP2C19 유전자형에 따라 사용하는 PPI의 용량을 다르게 사용하는 방법이 있을 수 있다.

기존 메타분석에서 CYP2C19의 영향을 덜 받는 것으로 알려진 rabeprazole을 투여하였을 때는 CYP2C19 유전자형에 상관없이 높은 H. pylori 제균율을 보였다[45-47]. 2013년 중국에서 Tang 등[48]이 무작위 배정 연구만을 대상으로 메타분석을 하였을 때 omeprazole과 lansoprazole은 CYP2C19 유전자형에 따라 제균 성공률의 차이를 보였으나 rabeprazole과 esomeprazole은 차이가 없음을 보고하였다. 우리나라에서는 lansoprazole과 rabeprazole을 이용한 표준 3제요법의 제균 성공률이 CYP2C19 유전자형에 따라 차이가 없음이 보고된 바 있다[49]. 하지만 2003년 MiKi 등[50]의 연구에서는 lansoprazole과 rabeprazole을 이용한 표준 3제요법의 제균 성공률의 차이를 보이지 못하였고, clarithromycin 감수성인 균주에서는 CYP2C19 유전자형에 상관없이 97% 이상의 제균 성공률을 보였다. CYP2C19 유전자형에 때라 PPI 용량을 조절하는 방법으로, 2011년 중국에서 Yang 등[51]이 omeprazole을 20 mg 사용하였을 때보다 40 mg 사용하였을 때 제균 성공률의 호전이 있음을 보였다. 하지만 다른 연구에서는 비슷한 용량의존 효과를 보인 연구를 찾아보기 힘들다. 이를 바탕으로, CYP2C19 유전자형에 따른 PPI 종류나 용량의 맞춤 치료는 재현성이 있는 연구가 필요하고, 항생제 내성과 상관없이 H. pylori 제균 치료에 대한 PPI 고유의 효과를 알아보기 위한 연구가 필요하다고 할 수 있다.

앞에서 알아본 항생제 감수성에 따른 맞춤 치료를 시행한 무작위 배정 연구 중, CYP2C19 유전자형에 따라 다른 PPI 용법을 사용한 연구를 살펴보면, Furuta 등[19]은 경험적 치료로는 lansoprazole 30 mg을 하루 두 번 사용하고, 맞춤형 치료에서는 신속대사자에게 lansoprazole 30 mg을 하루 세 번, 중간대사자에는 lansoprazole 15 mg을 하루 세 번, 대사저하자에는 lansoprazole 15 mg을 하루 두 번 사용하여 CYP2C19 유전자형에 따른 용량 및 용법을 변형하였다. 또한 Miwa 등[34]은 경험적 치료로 lansoprazole 30 mg을 하루 두 번 사용하고, 맞춤형 치료로는 omeprazole을 신속대사자, 중간대사자, 대사저하자에 각각 120 mg, 40 mg, 20 mg을 사용하여 용량의 변형을 주었다. 최근 Zhou 등[33]은 경험적 치료, 대사저하자, 중간대사자에 esomeprazole 20 mg을 하루 두 번 사용하고, 신속대사자에만 rabeprazole 10 mg을 하루 두 번 사용하여 치료약제의 변형을 주었다(Table 3). Rabeprazole은 lansoprazole이나 omeprazole에 비하여 CYP2C19이 적게 작용하는 비효소반응(non-enzymatic reaction)에 의해 위산을 저하시키므로 CYP2C19 유전자 다양성에 영향을 적게 받게 된다[52]. 이에 Sugimoto와 Furuta [53]는 rabeprazole 10 mg을 하루 네 번 투약하여 24시간 산분비를 억제시키고, clarithromycin 감수성을 확인하여 맞춤 치료를 하는 방법을 제시하였고, 맞춤형 치료에서 높은 제균 성공률(98.0% vs. 77.8%)을 확인하였으며, rabeprazole을 사용한 결과 CYP2C19 유전자형에 상관없이 신속대사자 94.3%, 중간대사자 98.3%, 대사저하자 100%의 일관적인 제균 성공률을 확인하였다. 이 방법은 유전자 검사의 비용을 절약하고 높은 제균 치료 성공률을 달성할 수는 있지만, 모든 환자가 CYP2C19 유전자형이 신속대사자가 아니므로 중간대사자와 대사저하자까지 rabeprazole을 다량 투약해야 하는 한계가 있다.

결 론

항생제 내성이 증가하면서 헬리코박터 파일로리의 제균 치료 성공률은 점차 감소하여 80%에도 미치지 못하고 있다. 항생제 내성은 국내에서도 지역 간 차이가 있으며, 다제내성을 보이는 비율도 높다. 이를 극복하기 위해 맞춤형 치료가 시도되고 있으며, 항생제 감수성을 확인하기 위해 전통적인 배양 검사를 기반으로 하거나, 보다 간단한 분자진단 방법도 연구되고 있다. 현재까지 맞춤형 치료는 대부분 clarithromycin을 기반으로 한 일차 경험적인 치료 방법에 비하면 일관되게 우월한 결과를 보여주고 있으나, 이차 요법에서는 아직 만족스러운 연구 결과가 없다. 다만 최근 분자진단 기법을 통해 모든 항생제 내성을 파악하였을 때 이차 요법에서까지 치료 성공률을 높일 가능성을 보여주었다. 위산 억제를 통한 제균 치료의 목적을 달성하기 위해 CYP2C19 유전자형 검사를 통한 PPI 투여의 다변화에 대한 연구는 아직 항생제 감수성을 기반으로 한 맞춤형 치료에 비해서는 연구실적이 부족하다. 향후 헬리코박터 파일로리 유병률이 점차 감소한다면 이러한 맞춤 치료의 역할이 더욱 중요해질 것으로 생각된다. 따라서 이와 관련한 국내 후속 연구들이 꾸준히 지속되어야 한다.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.