양성자펌프억제제 사용에 따른 위장관 세균총의 변화와 임상적 의미

Clinical Significance of Changes in Gut Microbiome Associated with Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors

Article information

Trans Abstract

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are commonly used for the treatment of gastric acid-related disorders, and are generally well tolerated. However, by reducing the secretion of gastric acid in the long term, PPI can increase the risk of inducing an imbalance in the gut microbiome composition. Moreover, gastric hypochlorhydria that is caused by PPIs favors the survival and migration of oral bacteria in the lower part of the gastrointestinal tract, with a possible induction of pro-inflammatory microenvironment. Therefore, gut dysbiosis that is associated with the use of PPI has been found to cause adverse infectious and inflammatory diseases. In this regard, adverse effects of the PPI-related gut dysbiosis have been reported in different observational studies, but their clinical relevance remains unclear. Therefore, the aim of this review was to explore the available data on the PPI-related gut dysbiosis in order to better understand its clinical significance.

서 론

양성자펌프억제제(proton pump inhibitor, PPI)는 소화성 궤양이나 위식도역류질환의 치료를 위하여 또는 비스테로이드성 소염 진통제 관련 합병증을 예방하기 위하여 광범위하게 사용되고 있다[1]. 일반적으로 PPI는 심각한 부작용의 발생 빈도가 낮은 안전한 약제로 간주가 되고 있기는 하지만 최근 다수의 관찰 연구에서 골절, 위장관 감염 그리고 영양 결핍 등의 부작용들이 보고되었다[2,3]. 미국에서 발표된 장기간의 코호트 연구 결과에서 PPI의 사용이 전체 인구 집단에서의 사망률 증가와 관련이 있는 것으로 보고가 되어 약제의 장기 사용에 따른 부작용의 역학적 근거를 제시하고 있다[4]. 특히, PPI 사용과 관련 한 장염 발생에 대한 관심이 높으며 여러 임상 역학적 근거가이를 뒷받침하고 있는데, 이러한 위장관 감염 유발의 요인이 약제에 의한 위장관 세균총의 변화로 추정되며[3,5], 이러한 위장관 세균총 불균형(dysbiosis)에 의하여 염증 반응이 초래되고 장 투과성이 증가하는 것이 중요한 위험 요인으로 알려져 있다[6]. 이와 같이 PPI를 사용하였을 때 위장관 세균총이 변하는 기전은 아직 명확하지 않다. 다만 PPI가 위 내의 산도를 높임으로써 미생물 환경을 변화시킨다는 가설과 PPI가 P형 ATP 분해효소(P-type ATPase)를 포함하는 세균의 양성자에 직접 작용하여 영향을 줄 수 있다는 가설이 제시되어 왔다[7]. 최근에는 고효율의 미생물 DNA 염기서열 분석법(high-throughput, microbial DNA sequencing)이 가능해지면서 인체 미생물군집의 특성을 잘 이해하게 되었으며, 이를 통하여 숙주와 미생물 그리고 대사산물 간의 상호 작용에 변화가 생기는 위장관 세균총 불균형에 대한 이해를 더욱 잘 할 수 있게 되었다[8,9]. 본고에서는 PPI 사용과 관련한 위장관 세균총 불균형의 변화 특성을 살펴보고 이와 관련한 다양한 감염성 혹은 염증성 임상 질환들의 발생 근거에 대하여 알아보고자 한다.

본 론

1. PPI 사용과 관련된 미생물군집 변화

위장관 세균총 불균형이 발생하면 미생물군집의 변화된 특성에 따라서 위장관 점막이 다양한 대사성 혹은 염증성 자극에 노출이 되며, 이러한 불균형이 장 투과성과 염증 반응을 증가시킴으로써 장벽 이상(barrier dysfunction)을 유도하여 잠재적인 전염증성 상태가 발생한다[10]. 위장관 미생물군집의 구성에 영향을 주는 많은 요인들이 알려져 있는데 항생제를 포함한 다양한 약제들, 유전적 요인, 음주, 식이, 인종 그리고 지역적 위치 등의 다양한 인자들이 이에 해당한다[10-12]. 타액과 위액을 이용한 한 연구에 따르면 PPI를 사용한 군의 위액에서 배양된 세균이 크게 증가하였지만 정량적 PCR과 16S RNA 유전자 분석을 통하여 세균의 수와 구성을 살펴보았을 때는 약제의 사용 여부에 따른 유의한 차이가 없었다. 즉, PPI 사용군에서 위 내의 세균 과증식이 발생하기보다는 구강으로부터 유입된 세균의 사멸이 적게 이루어지는 것으로 판단된다[13]. 또한 이 연구에서는 PPI 사용군에서 위액에서의 β-다양성(β-diversity)이 유의하게 증가하였는데 이의 임상적 의미는 명확하지 않다. 한편, 다른 연구에서는 정상인의 타액을 대상으로 4주 동안의 PPI 사용 전후의 변화를 16S RNA 유전자 분석을 통하여 평가하였는데, 타액에서 α-다양성(α-diversity)과 β-다양성에 유의한 차이가 있었으며 Leptotrichia가 유의하게 증가한 반면에 Neisseria와 Veillonella는 감소하였음을 보고하였다[14]. 최근에는 염기서열 분석을 통하여 PPI 사용군에서 분변 미생물군집을 분석한 인구 집단 기반의 환자 대조군 연구 결과들이 보고되었으며[13,15], 쌍둥이 코호트를 이용한 분석에서는 약제를 투여한 군에서 구강과 상부위장관에서는 상재균의 풍부도(richness)가 증가하지만 위장관 전체에서는 상재균 풍부도가 감소하고 미생물 다양성도 감소한다고 보고되었다[6]. 그리고 이 연구에서는 PPI 사용군에서 Streptococcus의 유의한 증가가 관찰되었다. 또한 독립적인 코호트로 구성된 1,815명에서 16S rRNA 유전자 염기서열 분석을 통하여 PPI 투여 후의 변화를 살펴본 다른 연구에서는 Staphylococcus, Streptococcus 그리고 Escherichia coli와 같은 Enterococcus가 20% 증가하였으며 대조군에 비하여 유의한 변화가 있었다. 그리고 각 코호트를 통합하여 분석을 하였을 때 PPI 사용군에서 α-다양성의 유의한 감소를 보였다[16].

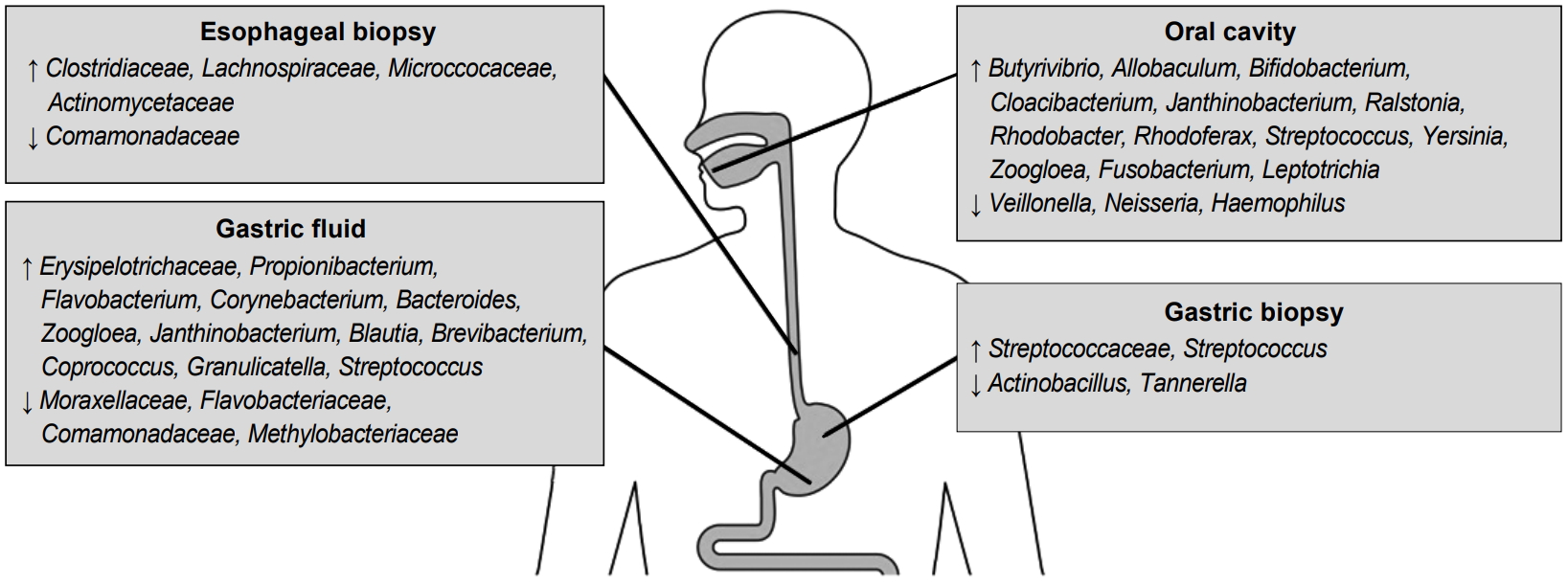

이러한 관찰 연구 이외에 비교적 혼란 변수를 배제하여 위장관 세균총의 변화에 대한 PPI의 영향을 살펴본 전향적 중재 연구들도 보고가 되었는데, 대부분의 연구에서 분변 검체를 이용한 분석 결과를 제시하여 상부위장관보다는 하부위장관에서의 세균총 변화에 대한 정보가 많다는 점은 한계이다(Table 1) [14,15,17-23]. 상부위장관의 세균총에 대하여 분석한 관찰 연구에서는 주로 위식도역류질환이나 소화불량증 등의 증상이 있는 환자군을 대상으로 하였으며 위나 식도 점막 조직, 위액, 타액 혹은 구인두 스왑을 이용하여 PPI 투약 후의 변화를 평가하였다(Fig. 1) [14,18,24-27]. 이들 연구마다 결과에 차이가 있어서 PPI 사용군에서 계통 발생 다양성(phylogenetic diversity)이 증가하였다는 보고가 있는 반면에 풍부도나 다양성 측면에서 유의한 차이를 보이지 않는 연구도 있다[26,27]. 위식도역류질환과 바렛식도 환자군을 대상으로 란소프라졸 투약 후 상부위장관에서의 미생물군집 변화를 살펴본 전향적 연구에서는 식도 점막에서는 Clostridiaceae, Actinomycetaceae, Lachnospiraceae 그리고 Microccocaceae의 증가를 보였고, 위액에서는 Erysipelotrichaceae의 증가 소견이 있었다[18]. 이처럼 차세대 염기서열 분석법을 이용하여 PPI의 위장관 세균총에 대한 영향을 분석한 그동안의 여러 연구들은 상부위장관과 하부위장관 모두에서 미생물 군집의 중등도의 변화를 유발하는 것으로 나타났다[28]. 그러나 그 임상적 의미에 관해서는 여전히 명확하지 않다.

Taxonomic Changes in the Gastrointestinal Microbiome Associated with the Use of Proton Pump Inhibitor and Identified from the Prospective Trials

2. PPI 연관 위장관 세균총 변화로 인한 임상 질환

1) Clostridium difficile 감염(Clostridium difficile infection, CDI)과 기타 장염

대장에서의 조직 생검과 분변 분석을 통한 연구들에 따르면 우점종은 Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria 그리고 Proteobacteria로 알려져 있다[29]. PPI를 사용하면 상부위장관에서의 위산 억제가 하부위장관의 미생물군집에 영향을 미치게 되는데 상재균의 감소, 다양성의 감소 그리고 분변에서의 구강 상재균의 증가 등이 특징이다[6,16]. Freedberg 등[15]에 의한 연구에서 PPI 사용 후 Streptococcaceae와 Enterococcaceae 군집의 변화가 CDI의 발생과 관련이 있음을 제시하였고, 또 다른 한 병원 기반의 연구에서는 대조군에 비하여 CDI 환자군에서 미생물 다양성이 감소하고 Enterococcaceae 군집이 증가하였다[30]. CDI 발생과 관련된 위장관 미생물에서의 구조적 변화와 기능성 변화를 조사한 연구에서 강력한 방어 균종의 대부분은 Firmicutes와 Clostridiales였고 CDI 환자에서는 더 낮은 미생물군집의 다양성과 풍부도를 보였으며, 반면 Bacteroidaceae, Enterococcaceae, Lactobacillaceae 그리고 Clostridium cluster XI와 XIVa가 더 증가하였다[31]. 이러한 변화는 PPI에 의한 위장관 미생물군집 변화에서도 동일하게 나타날 것으로 추정되어 PPI가 CDI의 위험인자로 고려될 수 있다. 이러한 CDI는 입원 환자에서 합병증 이환의 중요한 원인이며 상당한 의료 비용 지출을 유발하고 있는데, 항생제가 이 질환의 발생에서 중요한 위험 요인으로 확인되었지만 실제로 PPI 사용과의 관련성에 대한 임상적인 근거도 크게 증가하고 있다[32,33]. 메타분석 결과들에서도 PPI가 원발성 혹은 재발성 CDI의 빈도를 증가시킨다고 보고하고 있으며, PPI가 원발성과 재발성 CDI를 각각 2.34 (95% CI 1.94~2.82)와 1.73 (95% CI 1.39~2.15)의 교차비(OR)로 증가시킨다고 하였다[34,35]. 또한 Salmonella와 Campylobacter와 같은 다른 장염에 대해서도 PPI 사용군에서 각각 4.2~8.3과 3.5~11.7로 상대적 위험도가 증가함이 제시되었다[5].

2) 소장 내 세균 과증식(small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, SIBO)

소장에서의 세균의 밀도와 구성은 소장 통과 시간, 화학적 요인의 존재 여부 혹은 항생 물질의 존재 등에 의하여 차이가 있지만 일반적으로 Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Fusobacteria 그리고 Facultative anaerobe가 주된 우점종으로 알려져 있다[36-38]. PPI를 장기간 사용하게 되면 위산 방어 장벽의 손상으로 인하여 SIBO가 초래되는데, 이의 경우에 공장의 검체를 통하여 분석하였을 때 Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Escherichia 그리고 Klebsiella와 같은 미호 기성(microaerophilic) 세균과 Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, Veillonella, Clostridium과 같은 혐기성(anaerobic) 세균의 증가가 관찰되었다[39,40].

PPI 사용이 SIBO를 증가시킨다는 임상 보고에서는 Lo와 Chan [41]이 초기의 메타분석에서 2.28 (95% CI 1.24~4.21)의 OR로 위험도를 증가시킨다고 하였으며, 특히 하위 그룹 분석에서 SIBO의 진단 방법에 따라 그 위험도가 달라지는데 십이지장이나 공장에서 흡인 배양하는 방법을 이용하여 SIBO를 진단하였을 때 매우 높은 위험성 증가를 보였다(OR 7.59, 95% CI 1.81~31.89) [41]. 그 외에 19개의 연구를 대상으로 분석한 최근의 메타분석에서도 일관된 결과를 보이고 있으며 OR 1.71 (95% CI 1.20~2.43)로 중등도로 증가된 위험도를 제시하였다[42].

3) 자발성 세균성 복막염(spontaneous bacterial peritonitis)/간성뇌증(hepatic encephalopathy)

간경변 환자에서는 이미 Proteobacteria와 Fusobacteria와 같은 세균총이 증가하고 Bacteroidetes는 의미 있게 감소하는 것으로 나타나는데, 이에 PPI를 사용하였을 때 소장의 세균총에 변화가 더해지면서 간성뇌증이나 세균성 복막염의 위험도가 크게 증가한다[43,44]. 생쥐 모델을 이용한 한 전임상 연구에서 PPI에 의하여 위산 억제가 되면 장내 Enterococcus faecalis가 크게 증가하면서 알코올에 의하여 유발되는 만성 간질환을 더욱 악화시키는 것으로 보고한 바가 있어 장-간 축(gut-liver axis)에서의 위장관 미생물의 역할에 대한 관심을 불러일으켰다[45]. Qin 등[44]에 의한 연구에서는 정상인에 비하여 간경변 환자의 분변에서 Streptococcus와 Veillonella가 유의하게 증가된 것으로 나타났으며, 간경변 환자에서 장내 산도 변화와 담즙 분비 조절 장애로 인하여 구강 세균이 장관에까지 확장되어 이르는 것을 알 수 있었으며, 이에 더하여 PPI를 투약하였을 때 이러한 구강 세균의 장관 확장을 더 강화시키는 것으로 나타났다. 이를 통하여 PPI를 사용한 환자군에서는 정상군에 비하여 Streptococcaceae가 상대적으로 4% 증가하였고 간경변 환자군을 대상으로 분석하면 9% 이상 증가하였다[44]. 다른 연구에서는 PPI의 사용을 반영하는 혈청 가스트린과 분변에서의 Streptococcaceae 증가가 상관관계를 보여주고 있다[19]. 실제 임상에서 이러한 간경변 환자의 70% 이상에서 PPI를 사용하고 있다는 보고가 있어 약제 투약과 관련된 부작용은 임상적으로 매우 중요하다[46]. PPI와 자발성 세균성 복막염 발생 위험성 사이의 관련성에 대한 기전은 명확하지는 않지만 PPI가 SIBO의 위험성을 증가시키는데 기인하는 것으로 추정되며, 간병변 환자에서 장 투과성 손상으로 인하여 SIBO가 세균 전위(bacterial translocation)를 유발하여 자발성 세균성 복막염이 발생하는 것으로 생각된다[47].

이에 관한 임상 연구들에서는 환자 대조군 연구에서 OR 2.97 (95% CI 2.06~4.26)로 유의한 위험성 증가를 보였으나 코호트 연구를 대상으로 하였을 때에는 유의한 상관성을 보이지 않아(OR 1.18, 95% CI 0.99~1.14) 추후 잘 디자인이 된 연구를 통한 근거가 필요하다[48]. 또한 위장관 미생물군집의 변화는 암모니아를 증가시키고 염증과 산화스트레스 경로와 상호 작용하면서 간성뇌증의 발생에 중요한 역할을 한다[49,50]. 대만에서 시행된 코호트 내 환자 대조군 연구에서 일일 사용량 지수(defined daily dose)를 이용하여 분석하였을 때 PPI 사용군에서 명확한 위험성 증가와 함께 약제의 용량에 따른 위험도 증가도 보였다[51]. 최근에 간경변 입원 환자를 대상으로 한 코호트 조사에서 PPI 사용은 환자들의 30일 재입원율과 90일 재입원율을 증가시켰으며, 이는 PPI 사용군의 분변 분석에서 구강 상재균, 특히 Streptococcaceae가 높은 빈도로 확인되었고 자생적 미생물(autochthonous taxa)이 상대적으로 적은 빈도를 보였으며 PPI를 중단하면 구강 상재균이 감소하는 것으로 나타났다[21].

4) 폐렴

PPI 사용에 의한 상부위장관에서의 세균의 과증식이 세균 흡인의 위험성을 증가시키며 이로 인하여 지역사회 획득 폐렴의 발생 위험성이 증가하는 것으로 생각된다. 이러한 위산 억제와 폐렴 발생 간의 미생물학적 기전을 살펴본 분석에서 PPI를 사용한 지역사회 획득 폐렴 환자군에서는 원인균으로서 원래 보유하고 있는 구인두 균무리(endogenous oropharyngeal flora)가 유의하게 더 흔하였으며(OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.22~3.72), 특히 이들 PPI 사용 환자군에서 Streptococcus pneumonia 감염의 위험성이 2.23배 더 높았고 Coxiella burnetii 감염의 빈도는 더 낮음을 보인 바 있다[52]. 반면, 430명의 지역사회 획득 폐렴과 1,720명의 정상 대조군에서의 PPI 사용에 따른 폐렴 원인균의 차이를 분석한 연구에서 Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus 혹은 H. parainfluenzae와 같은 구인두 세균의 비율이 약제 사용 여부에 따라 유의한 차이가 없음을 제시하여 세균 과성장과 미세 흡인에 의한 기전보다는 PPI에 의한 면역 조절 효과에 의한 것이라는 의견이 있으며[53], 이는 약제에의하여 호중구에서의 부착 분자(adhesion molecule)의 발현을 억제하는 것으로 생각하는데, 이를 뒷받침하는 근거로 건강한 성인을 대상으로 한 연구에서 오메프라졸에 의한 활성산소(reactive oxygen) 생성의 억제와 호중구 식균 작용(neutrophil bactericidal activity)의 감소가 관찰되었다[54].

이와 같이 PPI의 사용과 폐렴 발생과 관련한 많은 역학적 근거들이 제시가 되었다[55,56]. 그러나 많은 연구들에서 대상군이 폐렴 발생의 위험 요인 중 한 가지인 위식도역류질환을 동반하는 경우가 많아서 원발성 비뚤림(protopathic bias)이 근본적이고도 중요한 문제가 되는데 이를 극복하기 위한 연구들이 소개되고 있다[57]. 한 연구에서는 위식도역류질환 환자군을 배제하고 비스테로이드성 소염제 연관 위병증에 대한 예방을 위하여 PPI를 사용하기 시작한 코호트만을 대상으로 분석하였을 때 PPI와 지역사회 획득 폐렴의 발생 간에 인과관계를 보이지 않았으며[58], 또한 자가 대조 환자군 디자인(self-controlled case series study)으로 수행한 다른 분석에서도 PPI와 폐렴 발생의 관 련성은 혼란 변수로 인한 것으로 결론을 내리고 있어 현재까지의 근거를 기반으로 하였을 때 PPI와 폐렴의 관련성은 명확하지 않다[59].

5) 담도 질환

담도 폐색으로 인한 담도 염증은 담관 내의 세균 증식에 의한 미생물군집의 불균형에 의하여 발생하는 것으로 알려져 있다[60]. 이에 더하여 담관 세균이 위장관 미생물의 역행성 감염(retrograde infection)으로부터 나온다는 점을 지지하는 많은 근거들이 있으며 더 나아가서 이러한 위장관 미생물에서의 변화가 담도계 질환의 발생과 관련되어 있다는 전임상 연구의 결과들도 보고되었다[61-63]. 특히, 파이로시퀸싱(pyrosequencing)을 통한 분석에서 담석이나 담도염 환자에서 위장관 세균총과 담관 내의 세균총에 유사함을 보인다고 제시하였고, 특히 근위부 소장에서의 미생물군집이 담관 내의 세균 밀도와 관련이 있는 것으로 나타났다[64-67]. 그러나 PPI 사용에 의한 위산 분비 억제가 담관 세균의 변화를 통하여 담도계 질환 발생에 주는 영향은 아직 임상적인 근거가 충분하지 않다. 한 연구에서 급성 담도염 환자를 대상으로 PPI 사용 여부에 따라 담관 내의 미생물 군집을 분석하여 비교하였는데 PPI 사용 환자군에서 담도 병원체의 수가 더 많고 범위가 다양한 것으로 나타났다[68]. 이 연구에서는 급성 담도염 318예에서의 병원균을 후향적으로 분석하였는데 PPI를 사용한 환자군에서 담관 병원균이 23% 증가함을 확인하였으며, 특히 Streptococcus를 포함한 구인두 상재균이 유의하게 증가한 것으로 나타났다(OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.1~2.9). 또 다른 환자 대조군 연구에 의하면 PPI의 사용은 급성 담낭염의 발생을 1.23배 증가시킬 수 있는 것으로 보고를 한 바가 있다[69]. 최근에 우리나라에서 인구 집단 기반의 코호트 분석을 시행하였으며, 그 결과 PPI를 사용한 군에서 그렇지 않은 군에 비하여 유의하게 높은 담도염 발생 위험성을 보임으로써(OR 5.75, 95% CI 4.39~7.54) PPI의 사용과 담도 세균총의 변화 그리고 담관계 질환 발생의 임상적 가능성을 제시해주고 있다[70]. 그러나 이의 관련성을 명확하게 하기 위하여 향후에 충분한 역학적 근거가 뒷받침되어야 할 것으로 보인다.

결 론

PPI는 위장관 내 세균총 불균형을 유발하는 것으로 알려져 있고 이와 관련하여 여러 위장관 질환 발생과 연관된 것으로 생각되며, PPI를 통한 위산 저하는 하부위장관 영역으로의 미생물의 이동과 생존에 중요한 영향을 주면서 위장관의 염증성 미세 환경을 만드는 것으로 보인다. 그러나 여전히 PPI에 의하여 유발된 위장관 세균총 불균형의 기능적인 의미에 대해서는 명확하지 않으며 임상적인 영향에 대하여 결론을 내리기에 근거가 충분하지 않다. 특히 대부분의 연구에서 대변 검체를 이용하여 분석이 진행되어 점막 관련 미생물군집의 변화를 적절하게 반영하지 못하는 경우가 많으며, 임상 연구에서는 혼란 변수에 의한 심각한 편의가 결과에 영향을 주는 경우가 많다. 또한 다양한 인종에서의 연구가 진행되지 않았으며 특히, 아시아 인종에서의 연구가 적다는 점도 관심을 가져야 할 부분이다. 이러한 이유로 향후에는 이런 한계를 고려하여 관찰 연구가 아닌 잘 디자인이 된 전향적 중재 연구를 통하여 이의 관련성을 명확하게 살펴볼 필요가 있다.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.