급성 정맥류 출혈의 내시경 치료와 예방

Endoscopic Treatment and Prevention of Acute Variceal Hemorrhage

Article information

Trans Abstract

Gastroesophageal varices occur in more than half of patients with cirrhosis and the incidence increases as liver function worsens. Although the mortality rate for acute variceal bleeding has decreased with the development of variceal endoscopic hemostasis and administration of vasoactive drugs and prophylactic antibiotics, it still reaches 20%. Therefore, surveillance of variceal occurrence and the prevention of their bleeding is very important in patients with cirrhosis. In patients with liver cirrhosis accompanied by portal hypertension, esophagogastroduodenoscopy should be performed to diagnose varices and stratify their bleeding risk. The interval of endoscopic surveillance is adjusted according to variceal condition and cirrhosis severity. If varices are diagnosed, primary prophylaxis (e.g., non-selective beta-blockers or endoscopic prophylaxis) is required to prevent variceal bleeding. Appropriate treatment, including timely endoscopic hemostasis, should be performed in patients with acute variceal bleeding, and secondary prophylaxis is required to prevent rebleeding. Endoscopic variceal ligation is the recommended endoscopic treatment for acute esophageal variceal bleeding; endoscopic variceal obstruction is usually recommended in patients with gastric varices. To prevent bleeding, endoscopic surveillance should be performed at regular intervals until the varices have been eradicated, and endoscopic followup should be performed periodically even after their disappearance. In this review, we investigate the role of endoscopy in the treatment and management of gastroesophageal varices.

서 론

정맥류는 간조직의 섬유화나 재생 결절에 의해 간문맥 내 혈류의 저항 증가와 산화질소(nitric oxide)의 감소로 간 내 혈관이 수축되면서 간문맥압이 항진되어 생성된 간문맥과 전신 순환계 사이의 곁순환(collateral circulation)이다[1-3]. 간 경변증 환자의 절반 이상에서 발생하고 간기능이 악화될수록 발생률이 증가하여 비대상성 간경변증 환자에서는 70%-85%까지 동반된다[4,5].

과거 정맥류 초출혈로 인한 사망률은 50%였으나 내시경 지혈술과 방사선 중재시술이 발전하고 혈관활성약물(vasoactive drugs)과 예방적인 항생제 사용 등으로 인해 사망률이 많이 감소되었지만 아직까지도 12%-22%의 높은 사망률과 출혈 후 제대로 관리되지 않으면 60%에 이르는 재출혈률이 보고되고 있다[6-10]. 급성 정맥류 출혈의 높은 사망률과 불량한 예후를 고려할 때 간경변증이 진단되면 정맥류의 발생 여부 및 출혈 위험도에 대한 평가가 필요하다. 특히 복수나 부종, 황달, 간성뇌증, 비장비대, 거미상 혈관종, 복부혈관의 우회순환(collateral circulation) 등 간문맥압 항진 소견이 있다면 정맥류가 발생했을 가능성이 높으므로 반드시 내시경 검사를 시행하여야 한다. 간경변증 진단 시 정맥류가 없었던 환자에서는 1년 이내 5%-9%, 2년 이내 14%-17%에서 정맥류가 발생하고 간경변증 진단 시 작은 정맥류가 진단된 환자에서는 1년에 12%, 2년에 25%까지 큰 정맥류로 진행되는 것으로 알려져 있다[11,12]. 내시경 추적검사는 정맥류가 없는 대상성 간경변증 환자에서는 2-3년, 비대상성 간경변증 환자에서는 1-2년 간격으로 시행하도록 권고된다[13,14]. 특히 간기능이 매우 악화되어 있거나 간손상이 지속되는 환자는 정맥류의 진행이 빠를 수 있기 때문에 내시경 추적검사의 주기를 단축하여 시행하는 것도 고려해야 한다.

본고에서는 급성 정맥류 출혈 시 적절한 치료와 정맥류 출혈을 위한 관리와 예방에 대해 알아보고 내시경 검사와 내시경 지혈술의 종류 및 역할에 대해 기술하고자 한다.

본 론

급성 식도정맥류의 출혈의 치료 및 예방

식도정맥류의 분류

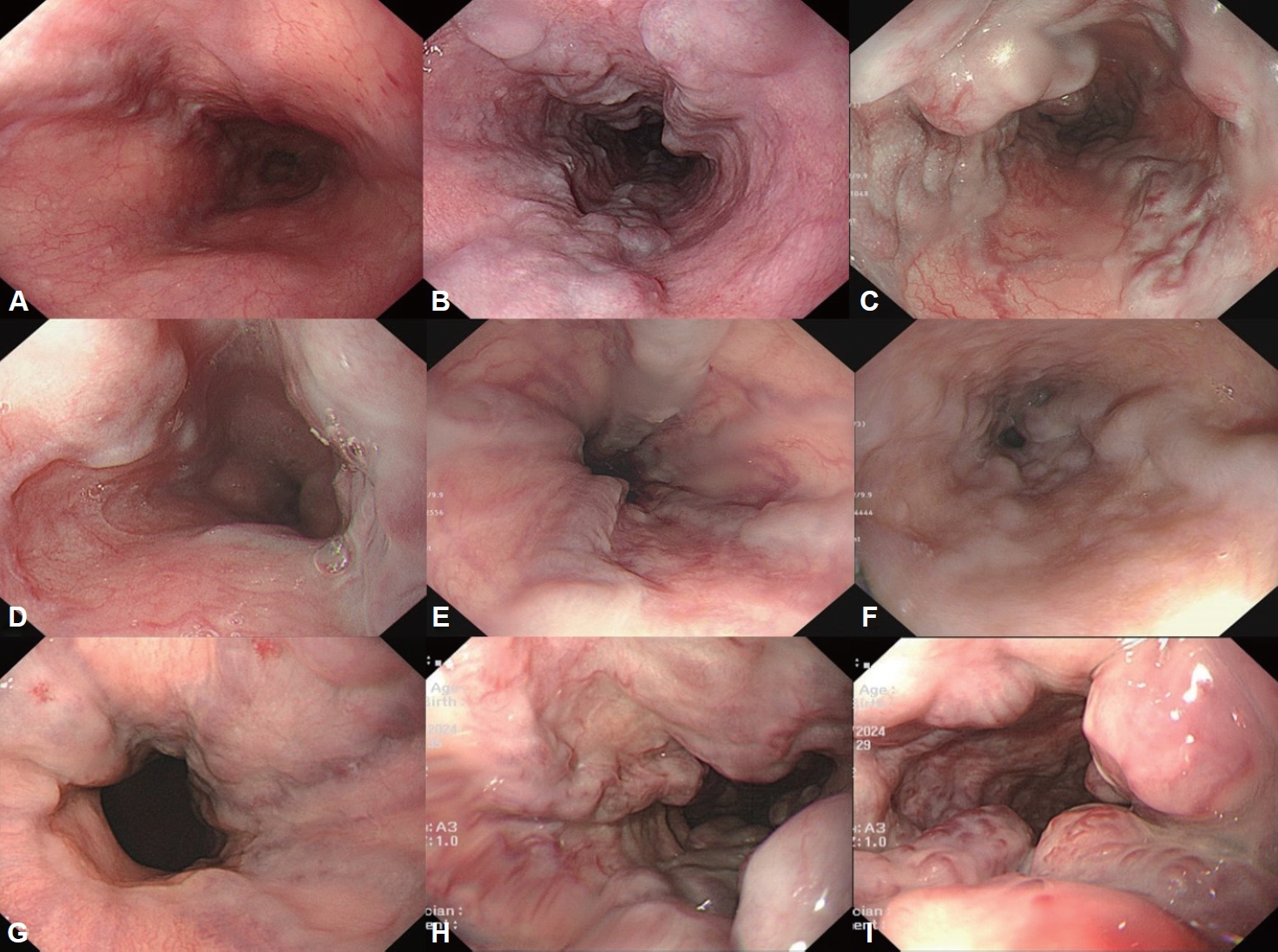

미국간학회에서는 5 mm 크기를 기준으로 작은 식도정맥류와 큰 식도정맥류로 분류하였고[15], 형태에 따라서는 식도 점막 위로 약간 융기되어 있는 경우를 작은 정맥류, 사행정맥(tortuous vein)의 형태로 융기된 정맥류가 식도 내강의 1/3 미만을 차지하는 경우 중등도 정맥류, 융기된 정맥류가 식도 내강의 1/3 이상인 경우는 큰 정맥류로 나누고 적색소견 동반 유무도 함께 기술하도록 하였다[16]. 일본문맥압항진증학회는 위치(location), 형태(form), 색조(color), 적색징후(red color sign) 소견에 따라 분류하였다. 위치에 따라 하부 식도에 국한된 정맥류(Li), 중부식도까지 진행된 정맥류(Lm), 상부식도까지 연결된 정맥류(Ls)로 나누었고, 형태학적으로는 직선 상으로 약간 융기된 정맥류(F1), 염주상 정맥류(F2), 결절형 정맥류(F3)로 분류하였다. 또한 정맥류의 색조에 따라 백색 정맥류(Cw)와 청색 정맥류(Cb)로 나누고, 적색소견의 정도에 따라서 적색소견 없음(RC0), 소수의 적색소견만 있는 경우(RC1), 중간 정도의 적색소견이 있는 경우(RC2)와 다수의 적색소견이 있는 경우(RC3)로 분류하였다(Fig. 1) [17,18]. 내시경 소견에 따른 정맥류의 분류는 크기와 적색소견 등 급성 출혈의 위험인자들을 포함하고 있어 향후 치료 방침을 결정하고 예후를 판정하는 데 도움이 된다.

Endoscopic classifications of esophageal varices. A: Esophagus shows straight and small-caliber varices (F1). B: The moderate enlarged tortuous beady veins are distributed in less than one-third of the esophageal lumen (F2). C: The marked enlarged nodular or tumorshaped veins occupies more than one-third of the esophageal lumen (F3). D: Whitish esophageal varices are observed (Cw). E: The esophageal varices are bluish in color (Cb). F: There was no red color sign (RCS0). G: The red color signs are small in number and localized (RCS1). H: The intermediated red color sign between RCS1 and RCS3 are observed (RCS2). I: The red color signs are large in number and localized (RCS3).

식도정맥류의 초출혈 예방

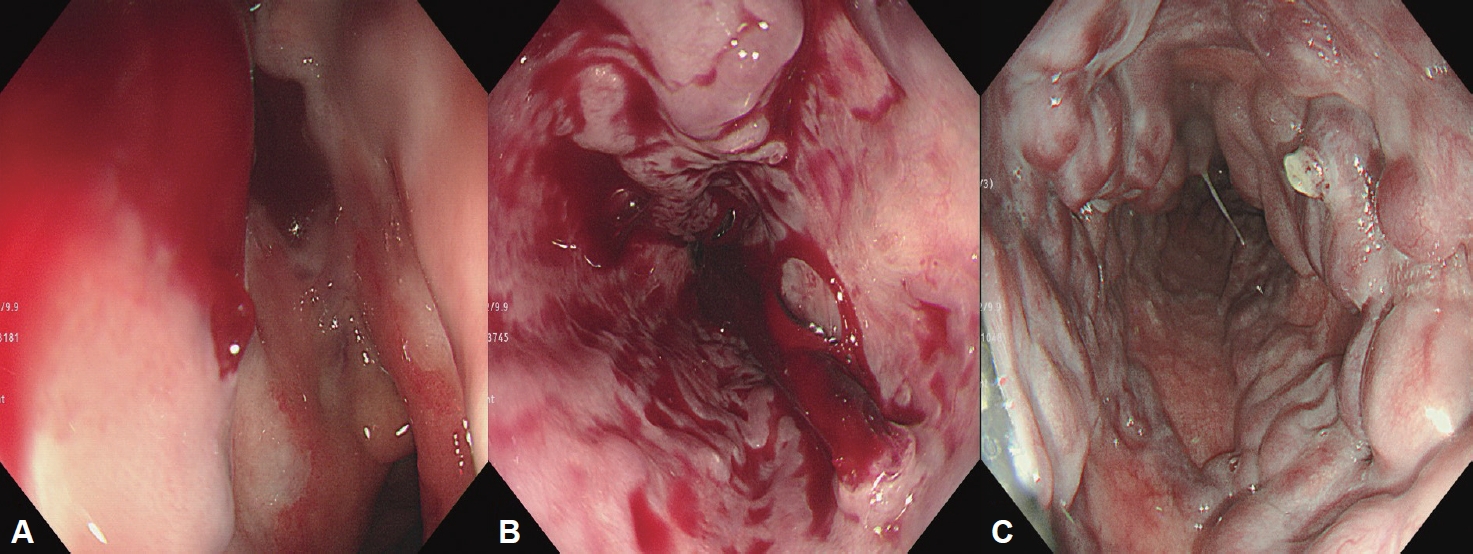

급성 정맥류 출혈은 활동성 출혈 외에도 정맥류를 덮고 있는 혈액응고(clot)나 정맥류 표면의 백색 유두(whitish nipple) 소견이 보이거나 정맥류 외 다른 출혈의 원인을 찾을 수 없는 경우에도 진단할 수 있다(Fig. 2) [15]. 식도정맥류 출혈은 연간 5%-15% 정도 발생하는데 크기가 가장 중요한 예측 인자로 5 mm가 넘는 F2 이상의 큰 정맥류에서는 15%의 높은 출혈률을 보이고, 적색징후가 동반되었거나 비대상성 간경변증(CHILD B/C)인 경우에도 고위험군에 해당한다[16,19]. 지난 수십 년간 정맥류 출혈에 대한 치료가 매우 발전하였음에도 불구하고 아직까지도 출혈 후 6주 이내의 사망률은 20%가 넘기 때문에[20-22] 고위험군 환자에서는 초출혈 예방이 반드시 필요하다.

Endoscopic features of acute esophageal variceal hemorrhage. A: Active spurting bleeding is identified in esophageal varix. B: A blood clot is attached to the esophageal varix. C: A white nipple is seen on the esophageal varix.

정맥류가 없는 경우에는 적절한 내시경 추적검사만을 시행하면 되지만[23], 크기가 크거나 적색징후를 보이는 고위험 정맥류뿐만 아니라[24,25] 작은 정맥류에서도 큰 정맥류로의 진행을 늦출 수 있어 초출혈을 예방하기 위해 비선택적 베타차단제의 예방적인 투여가 권고되기도 한다[26]. Propranolol이나 nadolol 등의 비선택적 베타차단제와 내시경 정맥류 결찰술(endoscopic variceal ligation, EVL)은 두 치료 간에 식도정맥류의 초출혈 예방 및 사망률에는 큰 차이가 없어 출혈의 위험도가 높은 환자에서는 환자의 상태와 약제에 대한 금기 및 부작용과 순응도 등을 고려하여 치료법을 선택하고[27-29], 저위험군에서는 비선택적 베타차단제를 먼저 투여하고 순응도가 낮거나 부작용이 있는 경우 EVL을 시행하는 것이 추천된다[16].

EVL은 내시경 선별검사를 하면서 바로 시행할 수 있고 특별한 금기가 없으며 비선택적 베타차단제와 비교하여 합병증 발생빈도가 낮으나, 고무밴드의 탈락으로 인한 식도 궤양과 출혈은 치명적인 합병증이 될 수 있다. 식도 궤양은 0.5%-3%까지 발생하는데[30,31] 양성자펌프억제제(proton pump inhibitor, PPI)의 투여는 궤양의 크기를 감소시키고 출혈을 줄일 수 있지만[32-34] PPI를 투여 받은 환자에서 간성뇌증과 자발성 세균성 복막염의 위험도가 증가하는데[35], 특히 간성 뇌증의 경우 사용 기간이 1-4개월, 4-12개월, 12개월 이상을 비교한 연구에서 사용 기간에 따라 위험도가 증가하였다[36]. 또한 최근 7일 이내 PPI를 투여한 환자군과 3개월 이내 사용한 적이 없는 환자군을 비교하였을 때 자발성 복막염의 발생이 증가하였다[37]. 따라서 간경변증 환자에서 PPI를 사용할 때는 사용 목적에 맞게 가능한 최소 기간을 사용하고 장기간 지속적으로 투여할 때는 간성 뇌증이나 자발성 복막염 발생 유무를 주의 깊게 관찰해야 한다.

식도정맥류가 없어지거나 결찰할 수 없을 정도로 매우 작아지는 경우 정맥류가 소실되었다고 판단한다. 초출혈 예방을 위해 1-2주 간격으로 정맥류가 소실될 때까지 내시경 정맥류 결찰술을 시행하도록 권고되었는데[16] 내시경 결찰술을 시행한 63명의 환자를 대상으로 한 연구에서 격주로 재결찰을 시행한 군과 격월로 시행한 군을 비교하였을 때 격주로 시행한 군에서 3차례의 결찰 후 정맥류가 더 많이 소실되었고 이후 재발률이 낮았다고 보고되었다[38]. 그러나 이후 1-8주의 다양한 간격으로 시행한 연구들의 결과를 바탕으로[39-45] 현재는 2-8주 간격으로 재결찰을 시행하고 정맥류가 소실된 이후에는 6개월 이내 재평가 후 6-12개월 간격으로 내시경 추적 검사를 시행하도록 권고하고 있다[25,43,46].

EVL과 비선택적 베타차단제의 병합치료는 단독치료와 비교 시 출혈률과 사망률에서는 유의한 효과가 없으나 정맥류 소실 후 재발률을 감소시키므로 고위험군 환자에서 선택적인 시행을 고려해 볼 수 있다[43,47].

Carvedilol은 문맥압을 효과적으로 감소시키면서도 부작용 발생이 적은 베타차단제로 전통적인 비선택적 베타차단제나 EVL과 비교하여 식도정맥류의 초출혈 예방 효과가 비슷하다고 보고되었다[48,49].

급성 식도정맥류 출혈의 치료

모든 위장관 출혈과 마찬가지로 정맥류 출혈에 있어서도 혈역학적 안정과 호흡 유지가 무엇보다도 중요하다. 그러나 간경변증 환자에서 과도한 수액의 공급은 오히려 문맥압 항진을 유발하여 정맥류 출혈을 악화시킬 수 있으므로 주의해야 한다. 급성 위장관 출혈의 경우 헤모글로빈이 7 g/dL 미만 시에만 농축 적혈구 수혈을 하는 제한적 수혈이 권고되는데 급성 정맥류 출혈에서도 이 기준에 따라 수혈하여 헤모글로빈 수치를 7-9 g/dL 정도로 유지하는 제한적 수혈은 사망률과 수혈로 인한 부작용을 감소시킨다[50]. 아울러 연장된 프로트롬빈 시간과 감소된 혈소판 수치를 교정하기 위한 신선동결혈장이나 혈소판 수혈은 출혈 경향을 교정하는 데 효과가 명확히 입증되지 않고 오히려 문맥압 항진을 악화시킬 수 있어 일반적으로 권장되지 않는다.

예방적 항생제는 세균 감염을 줄이고 재출혈 및 사망률을 감소시키므로 간경변증 환자에서 급성 위장관 출혈이 의심되면 내원 당시부터 바로 투여해야 하는데 7일 이내의 1일 1 g의 ceftriaxone 정맥 내 투여가 권장되고 있다[51,52]. Terlipressin, somatostatin, octreotide 등의 혈관활성약물은 내장기관으로 유입되는 혈류량을 줄여 문맥압을 감소시킴으로써 지혈 성공률을 향상시키고 사망률을 줄이므로[53,54] 내원 시 바로 투여를 시작하고 3-5일 정도 지속하도록 권장되고 있다[24,25]. 혈액의 흡인을 막기 위해 내시경 검사 시행 전 기관 내 삽관도 시행할 수 있으나 많은 연구에서 기관 내 삽관을 시행한 환자군에서 예후가 더 불량하여 간성 뇌증 등으로 자발적인 기도 유지가 어렵다고 판단되는 경우에 한해 신중히 고려해야 한다.

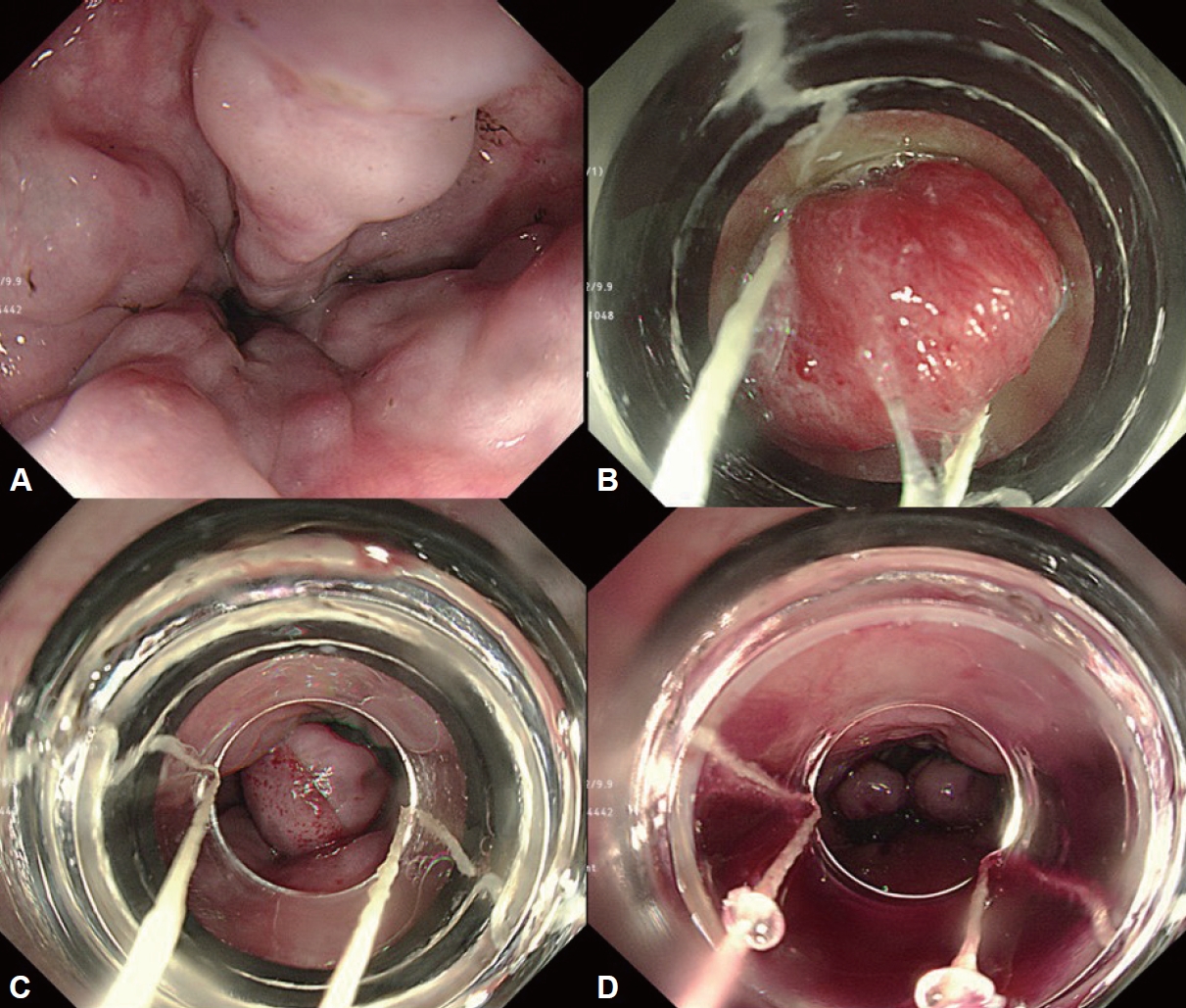

급성 정맥류 출혈이 의심되는 경우에는 혈역학적으로 매우 불안정한 출혈 환자에 준해 빠른 시간 내에 내시경 검사를 시행하여 정맥류 출혈 유무를 확인하여 내시경 지혈술을 시행해야 하는데 가능한 내원 12시간 이내 조기 시행을 권장한다[16]. 급성 식도정맥류 출혈에서는 EVL이 일차적인 표준 치료로 권고되고 있다. 내시경 선단부에 고무 밴드가 장착된 투명 캡 형태의 결찰 장치를 거치한 후 정맥류에 접근시킨 후 정맥류를 결찰 장치 안으로 충분히 흡인하여 끌어드린 후 고무 밴드를 발사하여 결찰하는데 이때 정맥류와 고무밴드가 장착된 투명 캡이 너무 밀착되어 있으면 정맥류가 잘 흡입되지 않기 때문에 정맥류와 캡 사이가 너무 밀착되지 않은 상태에서 흡인을 해야 한다. 출혈양이 많아 정확한 출혈점을 확인하기 어려울 때는 출혈이 있는 정맥류의 원위부에서 결찰을 시행하면 출혈량이 줄어들어 출혈점을 쉽게 찾을 수도 있다. 출혈 부위에 대한 결찰 후에는 정맥류를 소실시켜 재출혈을 예방하기 위해 남아 있는 다른 정맥류들도 가능한 결찰한다(Fig. 3). 5% Ethanolamine oleate, sodium morrhuate와 같은 경화제를 이용한 내시경 주사경화요법(endoscopic injection sclerotherapy, EIS)은 경화제를 정맥류에 바로 주입하거나 주변으로 주입하는 경우도 있다. 90%의 지혈 성공률을 보이지만 발열, 천자로 인한 출혈, 식도의 궤양 및 지연성 출혈, 협착 및 천공, 종격동염, 기관지식도류, 감염 등 다양한 합병증이 발생할 수 있고, 5% ethanolamine oleate는 다량 투여 시 용혈작용으로 인해 헤모글로빈뇨와 신부전이 발생할 수 있어 투여 용량을 0.4 mL/kg이 넘지 않도록 주의해서 사용해야 한다. EVL이 EIS에 비해 더 빠르게 정맥류를 소실시키고 재출혈률이 낮고 부작용이 적으며 생존율이 높다고 보고되어 현재 EIS는 식도정맥류 출혈의 일차치료로는 권장하지 않고 EVL이 실패하거나 결찰술을 시행할 수 없는 경우에 시행하도록 권고하고 있다[30,55-62]. 급성 정맥류 출혈 환자에서 내원 2시간 이내 내시경 검사를 시행하여 지혈분말을 도포한 후 내원 12-24시간 내에 EVL이나 내시경 정맥류 폐쇄술(endoscopic variceal obturation, EVO)을 시행한 경우 대조군과 비교하여 지혈률을 높이고 사망률은 낮추었다고 보고되기도 하였으나 지혈분말(hemostatic powder)의 효과에 대해서는 향후 추가적인 연구가 필요하다[63].

Endoscopic variceal ligation for esophageal varices. A: Endoscopy reveals a white nipple on the esophageal varix. B: Place the endoscope as close as possible to the esophageal varix and pull sufficiently into the ligation device through suction. C: Ligation esophageal varix by firing a rubber band. D: Additional ligations of remaining varices are also performed.

내시경 지혈술이 실패한 경우 구제요법으로 목정맥경유간내문맥전신순환션트(transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, TIPS)를 시행하는데 90%의 높은 지혈 성공률을 보였다[64]. 구제요법 시행 전 출혈양이 많아 혈역학적으로 불안정한 경우에는 가교치료로 S-B 튜브(Sengstaken-Blakemore tube) 등을 이용한 풍선 탐폰 삽입술를 시행하는데 80%-90%에서 지혈이 되지만65 탐폰 제거 후 재출혈 위험도가 높고 식도 파열 등의 심각한 합병증을 유발할 수 있어 24시간 이내 TIPS 등을 시행해야 한다[66]. 자가팽창형 금속스텐트도 가교치료로 사용할 수 있는데 풍선 탐폰 삽입법과 비교하여 사망률의 차이는 없었으나 지혈률이 의미 있게 높았고 부작용의 발생은 적으며 구제요법 시행 전까지 좀 더 긴 기간동안 사용할 수 있는 장점이 있다[67].

식도정맥류의 재출혈 예방

식도정맥류의 재출혈은 초출혈 이후 6주 내에 50% [68], 2년 이내 60% 정도에서 발생하고[10,69,70] 20%-40%의 높은 사망률이 보고되고 있어 재출혈을 예방하는 것이 중요하다[71]. 비선택적 베타차단제 투여와 EVL을 비교하였을 때 단독 요법으로 사용 시 두 치료법 간 재출혈률의 차이는 없었지만[28,72,73] 두 치료를 함께 시행한 경우 각각의 단독 요법에 비해 재출혈 발생이 줄어든다고 보고되고 있어 병합요법이 정맥류의 이차 예방를 위해 가장 적절한 일차치료로 추천되고 있다[74,75]. 재출혈 예방을 위한 결찰 주기는 일차 예방과 같이 1-2주 간격이 권고되었고[16] 평균 2-4회 정도의 추가 결찰을 시행한 후 정맥류가 소실되었는데[76] Harewood 등[77]의 연구에 따르면 2주 이내로 결찰 주기가 짧은 환자군에서 오히려 재출혈이 더 많이 발생하였고 연령, 성별, 간기능 상태를 보정했을 때 3주 이상의 간격으로 결찰한 군에서 재출혈이 적어 2차 예방을 위한 EVL도 1-8주 정도 간격을 두고 시행하는 것이 적절하다고 판단된다[60].

TIPS는 비선택적 베타차단제와 EVL의 병합요법과 비교하여 재출혈률이 낮았지만 간성 뇌증 등 합병증으로 인해 일차치료로 권장되지는 않고 병합요법을 시행함에도 재출혈이 발생한 경우 구제요법으로 시행된다[68,78]. 이러한 여러 치료법에도 식도정맥류 출혈이 재발하는 경우에는 간이식을 고려 해야 한다[79,80].

급성 위정맥류의 출혈의 치료 및 예방

위정맥류의 분류

위정맥류는 식도정맥류의 동반 유무에 따라 위식도정맥류(gastoesophageal varices, GOV)와 단독 위정맥류(isolated gastric varices, IGV)로 나누고 정맥류의 위치에 따라 세분화 한다. GOV는 위 소만을 따라 발생한 GOV1과 위 저부에 위치한 GOV2로 세분된다. 위저부에 발생한 IGV는 IGV1, 그 외 다른 부위에서 관찰되는 경우를 IGV2로 분류한다. IGV1의 경우 간경변증 외에도 췌장 질환에 의한 비장정맥의 혈전증으로 인해서도 발생할 수도 있다. 발생 빈도를 보면 GOV1이 70%를 차지하고 GOV2가 21%, IGV1이 7% 정도로 보고되고 있고 출혈 빈도는 IGV1이 78%로 가장 높고 GOV2가 55%인데 반해 GOV1과 IGV2는 10% 정도이다[81]. 위정맥류는 식도정맥류에 비해 발생 빈도는 낮지만 정맥류가 크고 점막하층에 더 깊게 위치하며 큰 정맥으로 바로 연결이 되어있기 때문에 대량 출혈이 발생할 수 있어 사망률이 높다. 또한 내시경 접근이 어려운 위저부나 위체부 후벽 등에 주로 발생하기 때문에 내시경 지혈술이 어렵고 지혈이 성공하여도 재출혈이 더 많이 발생한다[81-83]. 급성 위정맥류 출혈은 25%에서 진단 2년 이내에 발생하는데81 식도정맥류와 마찬가지로 크기가 크거나 적색징후가 동반된 경우 그리고 비대상성 간경변증의 경우 위험도가 증가한다[81,84-86].

위정맥류의 초출혈 예방

GOV1의 경우 초출혈 예방을 위해 식도정맥류에 대한 EVL을 시행하면 2/3에서 GOV도 함께 소실된다[87]. GOV2나 IGV1에서는 시아노아크릴레이트(cyanoacrylate)를 이용한 EVO가 권고된다. Mishra 등[88]은 위정맥류 환자에서 초출혈 예방을 위해 EVO를 시행한 군에서 26개월간의 추적관찰 기간 동안 13%에서만 초출혈이 발생하여 비선택적 베타차단제와 비교하여 더 효과적이면서 생존율도 높았다고 보고하였다. 내시경 치료나 비선택적 베타차단제 투여 외에도 위정맥류의 초출혈 예방을 위해 풍선차단역행경정맥 폐색술(balloon-occluded regtrograde transvenous obliteration, BRTO) 및 혈관마개 보조 역행 경정맥 폐색술(vascular plug-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration, PARTO) 등 방사선 중재 시술 시행을 고려해 볼 수 있다[89-91].

급성 위정맥류 출혈의 치료

급성 위정맥류 출혈의 경우에도 식도정맥류 출혈과 마찬가지로 terlipressin, somatostatin 또는 octreotide와 같은 혈관수축제와 항생제를 바로 투여하고 12시간 이내에 내시경 검사를 시행하여 출혈 부위를 확인하고 지혈술을 시행하도록 권고되는데 내시경 시행 전 환자를 혈역학적으로 안정시키고 기도를 확보한 후 적절한 장비를 갖춘 환경에서 경험이 많은 내시경 의사에 의해 시행되는 것이 바람직하다[92].

급성 위정맥류 출혈에서 가장 먼저 권고되는 내시경 지혈술인 EVO는 시아노아크릴레이트를 정맥류에 주입하면 수분과 접촉하여 중합체를 형성하면서 굳는 특성을 이용한 치료법이다(Fig. 4). 수분과 접촉하면서 쉽게 경화되기 때문에 시술 시 주의가 필요한데 내시경 렌즈나 겸자공으로 유출되어 시술 도중 내시경 시야가 가려지거나 내시경이 손상될 수 있어 검사 전 내시경 겸자공으로 올리브 오일을 흡인하여 채널 내부에 고르게 발라주는 것이 좋다[93].

Endoscopic variceal obturation for gastric varices. A: Active bleeding is identified in GOV2. B: After endoscopic variceal obturation, gastric variceal bleeding is successfully stopped. A polymer of cyanoacrylate is observed at the puncture site.

천자침이 너무 가늘면 접합제를 빠르게 주입할 수 없고 도관 내에서 굳어버릴 수 있기 때문에 21-22 G 정도의 굵은 천자침을 사용하는 것이 좋고 점막하층 심부에 위치한 위정맥류까지 가능한 깊숙히 천자하기 위해서는 5 mm 이상의 주사바늘이 긴 것을 사용해야 한다. 시술 도중 접착제가 시술자나 보조자의 눈에 들어가면 안구 손상을 유발할 수 있어 시술에 참여하는 의료진은 고글과 같은 보호장구도 필히 착용해야 한다. 천자 부위를 결정할 때는 정맥류 중앙의 돌출 부위는 정맥류의 압력이 집중되어 있기 때문에 피하는 것이 좋다. 분출성 출혈 시 출혈점에 직접 천자하는 경우 혈액이 천자침을 타고 흘러 시야가 흐려지는 경우도 있으니 주의해야 한다. 가능한 내시경을 천자 부위에 가깝게 위치시킨 후 도관에 생리식염수 1-2 mL를 관류시킨 다음 천자하고 시아노아크릴레이트가 빠르게 경화되는 것을 막기 위해 반드시 주입 직전에 주사기에 옮겨 리피오돌(lipiodol)과 함께 혼합하여 사용해야 한다. 일반적으로는 1:1의 비율로 혼합하여 1-2 cc 정도씩 반복적으로 주입하는데 위정맥류의 크기가 크고 혈류 속도가 빠르다고 판단되거나 십이지장을 포함한 다른 장기에 발생한 정맥류의 경우에는 시아노아크릴레이트의 비율을 60%-70%까지 높여 혼합하여 2 cc 이상 투여하기도 한다. 주사기 내 용액을 모두 주입한 후에는 1 cc 정도의 생리식염수를 추가적으로 관류하여 도관 내의 남은 혼합액들까지 모두 정맥류 내로 주입한다. 천자침이 정맥류 내에서 응고되는 것을 예방하기 위해 주입이 끝난 후에는 바로 천자침을 빼내고 천자부위에서 흘러나오는 시아노아크릴레이트가 빨리 고형화 되도록 생리식염수를 추가적으로 뿌려준다. EVO의 지혈 성공률은 90% 이상이나 1년 이내 재출혈이 17%-49%에 이른다[94-98]. 정맥류가 크고 유속이 빠르거나 시아노아크릴레이트의 혼합 비율이 40% 이하로 낮아 경화가 늦어진 경우 시술 후 5% 정도에서 중합체가 위신단락(gastrorenal shunt)을 통해 대정맥으로 유입되면서 색전으로 인한 전신 합병증을 유발하는데[99] 뇌와 폐, 문맥 색전증, 문맥혈전, 비정맥혈전, 비장 폐색, 후복강 농양, 위궤양, 천공과 복막염 등이 발생할 수 있고[100-107] 시아노아크릴레이트 용량이 많거나[108] 위신단락이 큰 경우에 더 많이 발생한다[109]. EVO 후 PPI 투여는 재출혈 위험을 낮출 수 있다고 보고되었다[110].

GOV1은 좌위정맥(left gastric vein)과 연관되어 있어 식도정맥류가 소실되면 함께 소실될 수 있어 EVL을 시행할 수 있는데 80%-90%의 지혈 성공률과 14%-56%의 재출혈률이 보고되었다[87,111-113]. 그러나 GOV1의 출혈에서도 EVO가 EVL에 비해 지혈 성공률이 높고 시술 후 재출혈이 낮으며[87,111-114] 2 cm 이상의 큰 GOV1은 EVL로 정맥류 전체를 결찰하기 어렵기 때문에 EVO를 시행하는 것이 좋다. 따라서 GOV1의 경우 환자의 상태, 정맥류의 크기와 출혈 양상 및 시술 의사의 숙련도 및 시술 환경 등을 고려하여 시술 방법을 선택해야 한다.

후방위정맥(posterior gastric vein)과 짧은 위정맥(short gastric vein)에서 기원하는 위바닥 정맥류(gastric fundal varices, GOV2 & IGV1)는 크기가 크고 정맥류를 덮고 있는 점막층도 두꺼우며 다량의 혈류가 빠른 속도로 흐르기 때문에 EVO가 일차치료로 권장되고[115,116], EVL이나 EIS로는 지혈이 어렵고 재출혈률이 높아 권장되지 않는다. 2 cm 이상의 큰 위정맥류에서 박리성 올가미(detachable snare)를 이용한 결찰은[117,118] 대부분 2년 이내 정맥류가 재발하였다[111].

내시경 지혈술이 실패한 환자에서는 TIPS와 역행 경정맥 폐색술(retrograde transvenous obliteration, RTO; BRTO or PARTO)과 같은 구제요법을 시행하는데 90% 이상에서 성공적으로 지혈이 이루어지지만 시술로 인한 합병증이나 금기증에 따라 신중히 고려해야 하고, 시술 가능한 단락의 확인이 필요하다. 구제요법을 시행하기 전 가교치료 시 S-B 튜브는 위부 풍선(gastric balloon) 용적이 200 mL 정도로 작아 위정맥류의 출혈에 대해서는 지혈이 제대로 이루어지지 않는 경우가 많다. Linton-Nicholas tube는 위부 풍선이 600 mL로 S-B 튜브에 비해 위바닥 정맥류를 좀 더 효과적으로 압박할 수 있어 50% 정도의 지혈 성공률을 보이지만 20%에서 재출혈이 발생하므로 구제요법 시행 전 가능한 짧은 시간 동안만 사용해야 한다[65,119].

위정맥류의 재출혈 예방

GOV1은 위정맥류 출혈을 지혈하면서 혹은 지혈 이후에 안정된 상태에서 동반된 식도정맥류를 2-8주 간격으로 반복적으로 결찰하고 비선택적 베타차단제를 병용 투여한다. 반복적인 결찰술로 식도정맥류가 소실 후 GOV1의 재출혈률은 16%-42%이고[111,112] 65%에서 위정맥류도 함께 소실된다고 보고되었다[87]. GOV1에서 EVO가 EVL보다 재출혈률이 낮다고 보고되고 있으나 좀 더 대규모의 전향적인 연구가 필요하다. 또한 내시경 지혈술에 비해 TIPS가 좀 더 재출혈을 예방하는 데 효과적이었다는 보고가 있지만 이 역시 아직까지는 근거가 부족하다.

반복적으로 EVO를 시행하여 위바닥 정맥류가 75%까지 소실되었다고 보고되었는데[109], 비선택적 베타차단제와 비교하였을 때 유의하게 재출혈률이 낮았다[120]. TIPS는 EVO와 재출혈률에는 큰 차이가 없으나 간성뇌증 등의 합병증 발생이 높았다[121]. 위바닥 정맥류의 재출혈 예방에 대한 방사선 중재술 간의 비교 연구를 보면 RTO가 TIPS에 비해 재출혈 예방에 더 효과적이나 간신단락이 없는 경우 시행할 수 없고 시술 후 식도정맥류가 악화되는 제한점이 있다[122].

결 론

급성 정맥류 출혈은 간경변증 환자에서 치명적인 합병증으로 정맥류의 상태 및 환자의 간기능의 중등도에 따라 위험도가 높아진다. 급성 정맥류 출혈이 의심되면 12시간 이내 내시경 검사를 시행해서 출혈 부위를 확인하고 내시경 지혈술을 시행해야 하는데 급성 식도정맥류 출혈에서는 EVL이 일차치료로 권고되고 있고 급성 위정맥류 출혈에서는 시아노아크릴레이트를 이용한 EVO가 권고되고 있다. 다양한 치료법의 발달에도 불구하고 아직까지 급성 정맥류 출혈이 발생하면 사망률이 높고 재출혈이 잘 발생하기 때문에 간문맥항진증이 동반된 간경변증 환자에서는 정맥류의 발생과 진행에 대한 내시경 감시(endoscopic surveillance)와 초출혈 및 재출혈 방지를 위한 적극적인 예방이 시행되어야 한다.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no financial conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

None

Acknowledgements

None